Everyone needs a hero. Some ideal to grow toward. To pursue as best as one can, however feebly, however clumsily. For some, that hero is God in Heaven; for others, that same God is a coward. “Show your face, you coward! Undo thy silence!” they yell. But God never complies. Besides, heroes don’t need to be real — fantasies will suffice quite nicely. And, of course, fantasies are all some have. Fantasies, and the labyrinthine internal rationale it sprouts, like saplings carpeting the forest floor, have created some of our most memorable heroes: Beowulf, Sherlock Holmes, Frodo Baggins. We could do worse than to follow their sense of moral clarity, how they weigh the forces of good and evil.

Everyone needs a hero. Some ideal to grow toward. To pursue as best as one can, however feebly, however clumsily. For some, that hero is God in Heaven; for others, that same God is a coward. “Show your face, you coward! Undo thy silence!” they yell. But God never complies. Besides, heroes don’t need to be real — fantasies will suffice quite nicely. And, of course, fantasies are all some have. Fantasies, and the labyrinthine internal rationale it sprouts, like saplings carpeting the forest floor, have created some of our most memorable heroes: Beowulf, Sherlock Holmes, Frodo Baggins. We could do worse than to follow their sense of moral clarity, how they weigh the forces of good and evil.

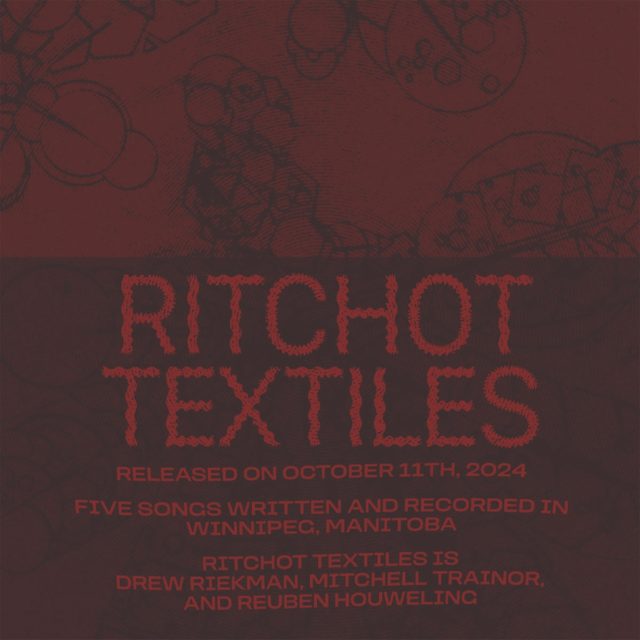

This is what Ritchot Textiles grapples with on i: this search for the self, as if one is lost in the forest, and how the self — the i in i — measures up with their concept of heroicity.

And it reminded me of the story of Ungod and the Arboretum, and what happened in Eurkeem.

What happened in Erukeem? Well, let me tell you:

When King K’lane of Erukeem heard that Queen Efira was pregnant, he was overcome with joy, and rushed into the Arboretum to meet her. He knew that’s where she’d be because of all the splendors of Erukeem — the Waterfalls of Gwenymyr, the Libraries of Citirax, Gost’s Tower; to name but a few — it was Erukeem’s Arboretum she loved the most. And that’s exactly where King K’lane found her.

“Is it true?” he asked, and when Queen Efira said that it was, the two embraced in perfect happiness.

“Then we must celebrate!” continued King K’lane. “The entire Kingdom must know!”

But Queen Efira contained her husband’s enthusiasm, and said to him: “Let us simply walk through the Arboretum instead, just you and I; with a child, Erukeem will soon become loud and boisterous, so let us enjoy this brief moment of calm and quietude, with only the trees as company.” And Queen Efira plucked a bright blue flower from a nearby Carcosa tree, and tucked its stem behind her ear; and the two walked through the Arboretum and beneath its vast tangle of trees of all kinds.

“Tell me of your favourite tree,” said K’lane. “Is it the Carcosa tree and its flowers whose blue is only surpassed by the blue of your beautiful eyes?”

Efira thought briefly and shook her head. “Although I have only seen it in drawings, if I had to choose, I would choose the parfum tree from the forests of Tresmir. Did you know it’s from them that we make parfum wine? But, to speak true, I love all trees; the smoothness or roughness of their bark; the pungency of their buds; the variety of their leaves and fruits and forms. How wonderful it would be to have each and every one of them represented here, in Erukeem’s Arboretum.”

King K’lane remembered her words, and so at the very next opportunity, he approached the Arboretum’s young gardener, Veldemen.

“Go to the Tresmirian forests,” he said to the boy, “And bring back the seeds of the parfum tree. Grow them here, in the Arboretum, but don’t let on about it to the Queen; I want it to be a surprise.”

So Veldemen did just that. He traveled east, through Pongir, and traded several gold kareen to a parfum wine merchant for the seeds. Upon his return, he found a secluded part of the Arboretum that was ideal for growing parfum. As the Queen’s belly expanded, so did the small shoots of the tree — at first so small and delicate, but very quickly it rose up and up until, after nearly 30 moons had come and gone, the parfum tree was fully grown; and from it several bottles of parfum wine were made.

But then tragedy struck: although a princess was born, Queen Efira died; and King K’lane, and all of Erukeem, mourned her death. She was buried at the base of the parfum tree, a tree she never saw; under its boughs lush with the scent of flowers she’d never smell; and its fruits that — either fresh or as parfum wine – she’d never taste.

King K’lane, drunk on misery, vowed to honour her desire: Erukeem’s Arboretum would be filled with every kind of tree that existed: from the Keetol Sea of the north to the Orun Sea of the south, and beyond, Efira’s Arboretum — as it would become known — would be home to them all.

Once again, King K’lane went to Veldemen, and said: “Go forth and bring back seeds of every kind, and plant them in Efira’s Arboretum so that her name becomes synonymous with one of the marvels of the world. It is in this way that her memory will be honoured. If you can do this for me – for I know of no other who could complete it — in return, I will offer you my daughter’s hand in marriage.” To which Veldemen dutifully agreed.

He went to Kreeth and found the milk pine; in Vanir, in the Yellow Woods, he found the parasitic Harkeef’s Angel; and in the Twilight Desert he found a stunted Ghost’s Fire, whose contorted limbs looked as if the tree were in constant anguish. From each – and many others – he collected their seeds; all of which he planted, grew, and maintained in Efira’s Arboretum in Erukeem. And after many years — of travel and toil — years in which the grounds of the Arboretum expanded as more and more specimens were added, years in which he watched Princess Solita grow into a beautiful young lady, Veldemen finally completed King K’lane’s request: every tree that existed was in the Arboretum.

Naturally, King K’lane invited the entirety of Erukeem to the grand opening, and Efira’s Arboretum was very quickly filled with those who had become curious about what was going on behind its tall walls. It was there that King K’lane, overwhelmed with gratitude, and with tears of joy in his eyes, announced that his daughter, princess Solita, would marry the royal gardener, Veldemen.

All of Erukeem seemed to be in attendance, and so it was that an old woman then came up to Veldemen and King K’lane while they discussed the details of the marriage. The woman had the look of an obali addict — spotted skin, thin hair, covered in dust — but, unlike an addict, her voice remained strong. She said: “Every tree, eh, gardener? Every tree, is it? My eyes aren’t what they used to be, but tell me: do you have Clemain’s Bell, the tree that grows underground?”

King K’lane looked to Veldemen, who nodded. “It’s in the south quarter, behind the diamondbark hedges.”

“Ah yes, yes, that seems about right,” she continued. “And what about the Gellevese snake tree, hmm? I don’t smell the rot of its flowers.”

“Too young by three years,” responded Veldemen, “but it lives. You passed it by upon entry.”

“I thought as much,” said the old woman. “Well, in that case: can you point me toward the Ungod tree? You know the one, right? Oh yes, you must, having collected every tree there is to be. The black cedar, some call it. The tree of shadows.”

King K’lane looked to Veldemen, whose eyes had narrowed with suspicion.

“There is no such tree, grandmother.”

“Oh but there is, gardener! There is. Clearly, you have not been to the Once Lands.”

“Nothing grows in the Once Lands — everyone knows that.”

“Ungod grows there. And grows well! I should know — I’ve seen it!”

Veldemen turned to the King. “Obalitic lies, your Majesty. Those eyes can barely keep their focus.”

“True enough, gardener — you speak true! But once they could see; and they saw the jagged plains of the Once Lands, and the horrors it vomits up, and, although my eyes be old, say true, they were once as young as the princess Solita’s; as surely as you are anxious to make her a queen, Gardener, I saw Ungod.”

“Only the Vanni would venture into the Once Lands.”

“True again, gardener! You speak true, do ya. I was once a wayfinder called Jiri. No longer, I’m afraid — those days have ended. Thanks to Ungod, I am both nameless and nothing. All that I had was taken from me. It is the way of the world, is it not, King K’lane? No matter how strong your grip, that which is most precious can be so easily ripped away.”

“And your Kaa?” queried Veldemen.

“Kaa-Jiri was lost. Killed, more likely.”

Here, the King wanted to know more, and so he asked for the old woman to tell her story, which she did.

“It was in Xel, your Majesty, where I came upon a pack of mutes — alchemical mutants, do ya know — and those I couldn’t kill outright I tracked into the sterile plains of the Once Lands. These mutes were different — I figured they inhaled human souls, for they ran like humans. Screamed like ‘em, too, when you got ‘em up close.

“Not too far from Xel, the mutes tried an ambush. You ever heard of a thoughtful mute? Not me — not then, anyways. But these ones had the gift of foresight, so when one rushed me, it was only thanks to Kaa-Jiri that I survived — filled ‘em with so many holes it’d make a colander jealous. She was a porcupine, Kaa-Jiri was. And when those mutes surrounded me, she let ‘em have it, you bet she did. A mistake, I now think. Should have died right then and there ‘cause then at least we’d have died together. But, no, she quills ‘em all dead, and the rest scatter like a cloud of flies.

“I kept my distance from then on, picking them off one by one with quill arrows. And all the while I went deeper and deeper into the Once Lands. The days became heavy, as if time were weighted down. And that’s when I came upon the last mute, who sat, as if it were waiting for me, under the black bough of Ungod.

“Kaa-Jiri warned me not to get too close, said it was another ambush. ‘There ain’t no ambush when there be only one left’, I remember telling her. Some of the last words we spoke to one another, it was. Was it a trap? If so, it weren’t the mute’s doing — thoughtful as it was, grinning through its burst boils and molding flesh, it weren’t the mute that strung me along. No, it were Ungod the Black.

“Don’t think I weren’t cautious as I approached the mute where he sat, legs crossed on one of the tree’s many thigh-like roots. Sitting in Ungod’s lap, it was. I sighted it true with a quill arrow. Its eyes were the colour of the tree’s bark. Have you ever heard a mute speak? No, I don’t imagine you have — that’s why they’re called mutes. Well, this one spoke. It was a putrid voice, and just hearing it you knew it came from a mouth rottener than an outhouse.

“ ‘Kaa-Jiri’, it breathed; the wind carried the words to my ears.

• • •

To read the rest of this review — and more by Steve Schmolaris — visit his website Bad Gardening Advice.

• • •

Steve Schmolaris is the founder of the Schmolaris Prize, “the most prestigious prize in all of Manitoba,” which he first awarded in 1977. Each year, he awards the prize to the best album of the year. He does not have a profession but, having come from money (his father, “the Millionaire of East Schmelkirk,” left him his fortune when he died in 1977), Steve is a patron of the arts. Inspired by the exquisite detail of a holotype, the collective intelligence of slime mold, the natural world and the suffering inherent within it — and also music (fuck, he loves music!) — Steve has long been writing reviews of Winnipeg artists’ songs and albums at his website Bad Gardening Advice, leading to the publication of a book of the same name.