There was always this fleeting sense of moving from a punishing world to a better place. Ducking through the front door, I’d leave the burning day tied to the sappy tree out front, dead locust shells clung to its branches. Inside it was cool and dark and the air was slit open with a turkey knife, stuffed with the scent of beer farts that had traveled from the early afternoon depths of his guts. Even now I can feel my sweat chilling on my skin. Even now I can move through the ripe pop of the room as it was when I first entered.

There was always this fleeting sense of moving from a punishing world to a better place. Ducking through the front door, I’d leave the burning day tied to the sappy tree out front, dead locust shells clung to its branches. Inside it was cool and dark and the air was slit open with a turkey knife, stuffed with the scent of beer farts that had traveled from the early afternoon depths of his guts. Even now I can feel my sweat chilling on my skin. Even now I can move through the ripe pop of the room as it was when I first entered.

The space was lit only by the day itself. Late morning, early afternoon, my Pop-Pop wouldn’t reach up to turn the old lamp on probably for the same reasons I don’t turn them on today. Lamp light is sadness. Lamp light is brighter than real truth ever has to be. So he sat in the glow of the small television that sat upon the much larger older television that acted like a piece of furniture designed to hold a TV. I’d never known the floor model to work. It had always just been sitting there, a smaller rabbit ear model living on the mammoth dead hill.

He was never disappointed to see me. Not once. Not ever. He always met my entrance with a ‘Hey Man’ and then asked me if I wanted a can of soda. If I did/ which I did/ he would say nothing more of it. We had our ways, our familiar routines. I’d go grab one from the fridge and crack it halfway back to where he was.

If there was a new hunting and fishing magazine that had arrived in the mail, he’d let me hold it in my hand. If he’d read it already, he’d say so, and I knew then that I could take it with me. I had a stack of them up in my bedroom at my mom’s and I would leaf through them on thick summer evenings as I dreamt about being the kind of young man that could go out fishing and hunting any old time. Articles told of upstate deer camps where men were men. Lakes I’d never seen, filled with walleye and pike and smallmouth bass. People catching wild trout in pristine mountain hollows. People searching for grouse with reliable gun dogs in thick sapling thickets, far from the suburbs of my world. Far from the hoagies and far from the dugouts where I used to wait my turn to bat but now I smoked one-hitters with my long-haired buddies.

If there was no magazine, we’d sit there together just watching the local news or a game show he was looking at. We’d small talk ourselves out of any deeper need for depth. Yet, I never felt as if I lacked real connection with him. It was almost as if the mere collision of our existences was enough. It was almost as if, even on the most mundane days, my grandmother dead and gone, the steady Chevys and trash trucks and semis out on Fayette Street barely audible through his closed windows, there was this sense of vast love between us. It was a love unspoken. The word itself was used, I’m sure, but rarely if ever. Even so, we were men and boys. We were troubled, I suppose, the same as anyone, but neither of us had any idea. We were both blind to what might have been building up inside ourselves.

And like a lot of people born when he was born, folks who had been kids during the Great Depression, he didn’t really seem to expect too much from this world. I never saw any ambition in him. I never knew him to want to move or even visit any places that weren’t directly connected to a funeral for a VFW friend or a rare meeting of the living vets off his USS Idaho.

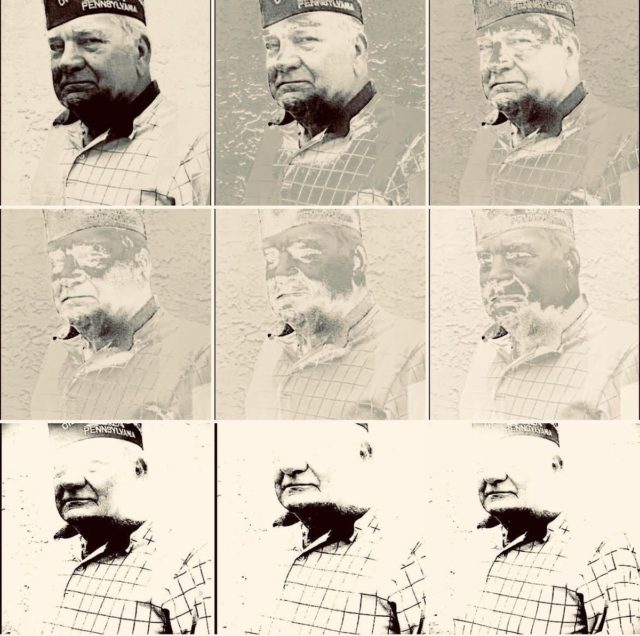

I looked at him as a steady, safe presence in my world.

My dad had disappeared years before. My mom was dating a new fellow. I was a teenage pothead who loved music and books and fishing and girls. Girls didn’t much care for me though. Probably because I also loved cheesesteaks and mozzarella sticks. I had no idea who I wanted to be in this life. And he never once gave me the old man speech about chasing my dreams or being all I could be, fucking blah, blah, blah.

He asked me if I wanted a soda. He asked me how I was doing. He looked at me through a cloud of his own gases and his eyes were gentle and sparkling with delight at the sight of me sitting there in the house he’d lived in with her for so very long. My mom had lived here all her young life and so did her little brother. Now they were grown and gone. And there was only me and my brother on days like this.

We lived right behind him. I’d go over alone. Just to see what was up.

Just to see what I could see when I was baked and lonely and unsure of anything in this impossible world.

My Pop-Pop was old then but not as old as I probably remember him. People are older when viewed through young eyes. It makes no sense but it also makes all the sense. I was about 17 so what would that make him? 64? 65? He hadn’t been working construction for years by then. A fall on a wedding dance floor had busted his leg years ago. He never really went back to regular life after that, I guess.

I struggle to remember who I was back then. Trying to put my finger on who he was proves nearly impossible. He was like a lot of men his age; he was blue-collar mean, but sweet to me; he was a drunk but he was caring. Except to his wife who he had loved a lot, I assume, but who he had treated quite terribly in the years I had known them both. He was cruel to her with words. It was psychological abuse. Back then though, even in the 1980s, it was just how a man could talk to his wife if he wanted to. He’d tell her the dinner she’d made him from scratch tasted like dog shit. He’d talk down to her about trivial things, as if any thoughts she shared were to be immediately shut down as stupid or wrong or both. He never seemed to notice her much unless he was being upset towards her.

It was a very broken human situation that neither party ever considered ending as far as I can tell. Although I often wonder if she might have left him if she could have. Conditions were never right for it though and I get that now. She was linked to him financially. And they were linked to each other in the eyes of the state and the community and maybe even God if either one of them actually believed in such a thing. To have thought of divorce would have been extremely out of character for my Mom-Mom. She was strong and loving and kind as fuck. She would have rather died than to have left Pop-Pop. So that’s what she kind of did. She lived in a state of perpetual dying/ insulted and thrown around emotionally/ until breast cancer freed her from the chains none of us ever admitted she was in.

Things were different back then, you see. People stayed together with people who were savagely brutal to them without even hitting them or anything like that. All the black eyes can be on the inside, you know. It can be a man abusing a woman like that for years, decades.

And it can be a woman abusing a man like that all the same.

Although people don’t like to talk about things like that.

Not just yet anyways.

In his car, on the Schuylkill Expressway, Pop-Pop would flip his cooler open that was down under the radio and he’d fish out a can of cream ale and he’d ask me to crack it open for him so he didn’t crash the Matador. I’d feel the chilled beer splash a little on my skin and I was never afraid. Not once. The idea of him drinking and driving with me in the car, just a kid, 10 years old, 11 years old, on our way to watch the Eagles play in Vet Stadium, it wasn’t something that brought fear into my heart like it would for one of my kids were they to experience something similar.

Not at all.

Instead, I loved the little flecks of beer smell that tattoo’d my fingertips and that trigger puller muscle of my little right hand when I opened his can for him. I loved handing him the drink as it foamed up out of its hole, the head spilling out onto this world like some long lost ocean coming up out of the ground. He’d thank me as he took over the can and I would feel accomplished and good and worthwhile.

We’d drive past Manayunk on the other side of the river and I’d look down at the row homes and factory buildings and distant tap rooms- still closed until later, when the game would come on- and it was out there in all of that that my grandmother’s people had come from. Buried up on that hill, in a cemetery behind a sleek silver diner, the bodies of her ancestors were evaporating in their unmarked graves. They’d been too poor to afford stones, I guess. I had no idea that this town had so much meaning in my life, of course. Pop-Pop never mentioned a single word about it across the many autumn Sunday morning trips to games we took together. Part of me thinks maybe he didn’t know. But that seems far-fetched to me now, too. One of Mom-Mom’s great grandfathers was buried over there. He’d fought at the Battle of Gettysburg.

How could they have not known that?

How could he have never heard that?

I can’t figure it out. Maybe he knew and just didn’t consider it worthwhile enough to mention to me even once?

Or maybe he had no idea.

Maybe people like him, people who were somehow broken in ways that no one ever knew about or talked about in those days, maybe those kinds of people just didn’t pay much attention to family stories. Maybe they were too preoccupied with just surviving.

Or maybe because it was her family and not his, he didn’t give a rat’s ass. And he told her to shut the hell up about it.

I don’t know for sure.

And I never ever will.

I just know I was happy. Young. Excited. Snow flurries here and there. East Falls. City skyline. A life unfolding before my eyes and all the days to come.

To read the rest of this essay and more from Serge Bielanko, subscribe to his Substack feed HERE.

• • •

Serge Bielanko lives in small-town Pennsylvania with an amazing wife who’s out of his league and a passel of exceptional kids who still love him even when he’s a lot. Every week, he shares his thoughts on life, relationships, parenting, baseball, music, mental health, the Civil War and whatever else is rattling around his noggin.