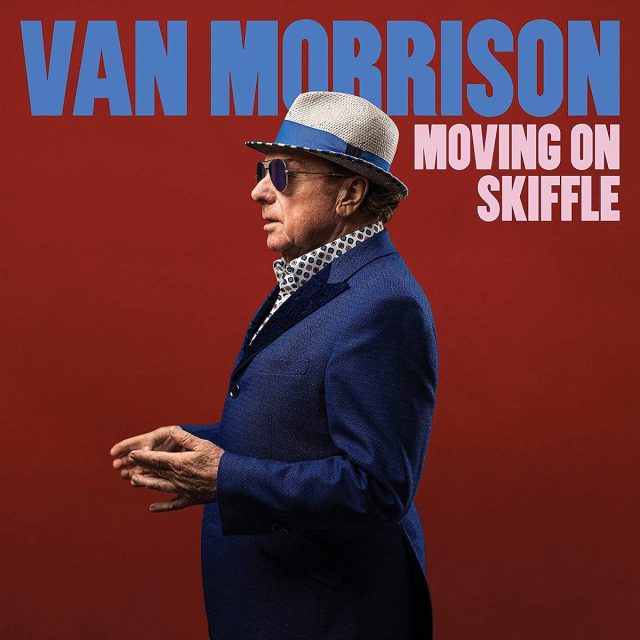

THE EDITED PRESS RELEASE: “It should come as no surprise that Van Morrison has made another album inspired by skiffle. Or that it takes a homemade style that exploded across Britain in the mid-1950s and brings to it a level of sophistication and soulfulness it didn’t always possess first time round.

Skiffle has its roots in the African-American jug bands of 1920s New Orleans, who got around a lack of funds for proper musical instruments by using washboards, tea chests, jugs and tubs to appropriate their own take on the country blues. By the time it reached the U.K., largely thanks to enthusiasts such as Ken Colyer, Chris Barber and Lonnie Donegan — who scored a massive hit in 1955 with his skiffle take on blues legend Lead Belly’s Rock Island Line — it became an entry point for a generation of callow British youth into the endlessly absorbing world of American blues, folk, jazz and country music. And nobody has inhabited that music, over an entire lifetime, as much as Morrison.

“I was still in school when I performed with a skiffle band — a couple of guitars, a washboard and a tea-chest bass,” says Morrison, who grew up in East Belfast, “I was already familiar with Lead Belly’s recordings, so when I heard Lonnie Donegan’s version of Rock Island Line I intuitively understood what he was creating. I knew that it was what I wanted to do. It was like an explosion. This record retranslates songs from that era.”

His love for American music began during childhood when his father would bring him to Atlantic Records, a famous shop in the heart of Belfast, to hang out and listen to music with proprietor Solly Lipsitz. There he would hear early 20th century folk, blues and jazz; music that started life in the prisons and fields of Mississippi and the bars and brothels of New Orleans. “I was in a smoky room, hearing Lead Belly and Jelly Roll Morton, and I connected with it early on,” he remembers. “I didn’t know I was going to do it professionally. One of the teachers at Orangefield School told me I was going to be a singer before I knew it myself.”

The skiffle genre is the thread running through Morrison’s diverse career. From the ’50s and ’60s spent listening to his heroes Donegan and Barber shaking up the music scene, to later recording the now-iconic The Skiffle Sessions – Live in Belfast 1998 with them. The recording included revitalised adaptations of Lead Belly’s Goodnight Irene and Jimmy Rodgers’ Muleskinner Blues. As these legends of skiffle sadly passed, Morrison was front and centre in honouring their legacy, performing at tribute concerts for Donegan in 2014 and Lead Belly Fest in 2015 at the Royal Albert Hall. Morrison also paid a personal tribute to Donegan in documentary Lonnie Donegan and Me.

Although he headed down a rock ’n’ roll path with several bands, showbands and later his R&B band Them, and explored the limits of jazz-rock with such spiritually inspired masterpieces as Astral Weeks and Moondance, Morrison has always returned to his first love sooner or later. Moving On Skiffle is essentially a tribute to that music, albeit one in which Morrison’s famously soulful voice takes these standards down new roads. Morrison discovered many of the songs through recordings by Chas McDevitt, a Scottish musician whose skiffle group performed in coffee shops and jazz clubs in 1950s London.

“McDevitt’s book is where to start when it comes to the history of skiffle,” says Morrison, referring to Skiffle: The Definitive Inside Story. “From the very beginning, with Lead Belly and the jug bands laying the foundations, through to Lonnie Donegan’s influence and Chas McDevitt’s skiffle group, it’s all in there.”

You might notice a few alterations along the way. The ever-rebellious Morrison has changed the title of Mama Don’t Allow, recorded by both The Memphis Jug Band and the Chicago bluesman Tampa Red in the late 1920s, to Gov Don’t Allow, a nod to his fight against the rise of totalitarianism. The gospel standard This Little Light of Mine, a key anthem of the Civil Rights movement in ’60s America, is transformed into the rollicking, upbeat This Loving Light of Mine, Morrison’s own plea for making the most of every day. For the most part, though, he’s playing it straight.

One of the highlights is Freight Train by Elizabeth Cotton, a former nanny for the folk singer Peggy Seeger. Cotton wrote the song as a teenager in the early years of the 20th century, after being inspired by the sound of the trains rolling down the tracks in her native North Carolina. Seeger took the song to England and played it in the folk clubs, after which McDevitt recorded a version of it in 1956 that became a major U.K. hit. Morrison has given the song a sophisticated jazz arrangement complete with rollicking organ, close harmony vocals and some new words in the second verse, but he has stayed entirely true to the sweet spirit of Cotton’s original.

Elsewhere, Wish I Was An Apple On A Tree takes an old American folk song, which became the basis for the hit Cindy by late ’50s rock ’n’ roller Ricky Nelson, and brings to it a wonderfully warm quality, complete with a jaunty washboard part by Sticky Wicket and treacle-rich backing vocals from Crawford Bell, Dana Masters and Jolene O’Hara. Morrison has also repurposed skiffle favourites about what matters in the modern age. The traditional folk ballad Gypsy Davey, a tale of a rich man’s wife who falls for a bohemian of no fixed address, has a timeless message on true love’s power. It featured on a 1956 recording by Barber, whose New Orleans Jazz Band was instrumental in introducing trad jazz to Britain, launching not only Donegan’s career but the skiffle boom in general. Meanwhile, a doo wop-styled rendition of Greenback Dollar finds Morrison asking for love, not money, over Dave Keary’s bluesy guitar and his own impassioned saxophone.

Moving On Skiffle ends with Green Rocky Road, a plaintive folk gem and an ode to the troubadour life that was made famous by Greenwich Village folkies Fred Neil and Dave Van Ronk and featured in a scene from Joel and Ethan Coen’s 2014 film set in New York’s early ’60s folk scene, Inside Llewyn Davis. It makes for a fitting finale to a 23-track album, which goes to the heart of the music Morrison has inhabited ever since those early years spent hanging out in the smoky confines of Belfast’s Atlantic Records. It also contains songs that underline, in their messages on the importance of freedom and living on your own terms, his lifetime philosophy. As Morrison puts it: “Freedom is not a given anymore. You have to fight for it. That’s where the blues come in.”