i was gonna write a long ass review about this album

it was gonna be about steve earle and death and country music and tradition

it was gonna be about townes van zandt and guy clark, justin townes earle and west virginia coal miners

about how steve speaks for them all

and how maybe that’s because he barely escaped ending up on that list

i was gonna write about honour and love and obligation and legacy and debt and family and how parents shouldn’t have to mourn and bury their kids

i was even gonna write about covid and opiate addiction

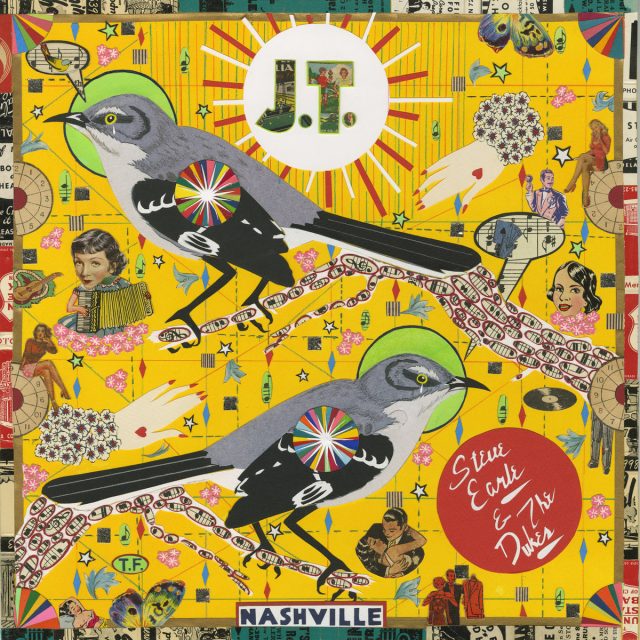

mostly of course, i was gonna write about this album

about how i can’t think of another artist who’s made an album like this

about how it wouldn’t exist if this world was a little better

about how it’s so goddamn heartfelt and beautiful and joyous and devastating

it’s pretty much guaranteed to make you cry

especially the original closing track last words, when steve sings “last thing i said was, i love you / and your last words to me were, i love you too”

i mean, jesus

after all he’s been through, sometimes i wonder how steve earle keeps soldiering on

keeps fighting the good fight

keeps speaking for the dead

keeps speaking for the living

keeps speaking for us all

honestly, i wouldn’t be able to do it

so i’m glad he does

i was gonna say all of that

then this arrived in my email

and it says everything that really needs to be said:

“A note from Steve…

Justin Townes Earle left this world a little over a mile from where he came in, having seen more of it than most folks in his 38 years before his all too short arc brought him right back to where he started from; Nashville, Tennessee.

The evening Justin was born, in what was then called Baptist Hospital, his mother, Carol, exhausted after 36 hours in labor fell immediately into a deep sleep and I was left staring into the eyes of my first-born son. After a while, a kindly nurse asked if I would like to carry him to the nursery myself. I don’t know how I ever negotiated the walk down the hall without tripping over my own two feet. I couldn’t take my eyes off him and he looked right back at me, hardly blinking, as if to say, “I know you.” After a bit of a gentle tug-of-war at the nursery door I reluctantly relinquished custody to the nurse.

My arms had never felt so empty. Suddenly it occurred to me that I hadn’t spoken to any of my family back in Texas since I’d phoned early the day before to let them know that Carol was in labor and we were headed for the hospital. I beelined for the payphones in the waiting room and was relieved to find a quarter in my pocket (not a given at that point in my career). I dropped it in the slot and dialed my parents’ number in Houston. My Dad answered and immediately upon hearing his voice, I burst into tears and apologized for every shitty thing I’d ever said or done to him, which was a litany.

Carol and I split up when Justin was 3 and he shuttled between our households, sometimes voluntarily sometimes not, until he left home. That event occurred pretty organically when he accompanied me on a teaching sabbatical to the Old Town School of Folk Music in Chicago.

Justin was playing by that time, having gone from post-mortem Nirvana fan to acoustic blues practitioner by way of Kurt Cobain’s Where Did You Sleep Last Night. He’d only been interested in electric guitar until seeing Cobain hunched over the big Martin acoustic on MTV Unplugged so I pointed him towards the original recorded version in my record collection. Leadbelly was next to Lightnin’ Hopkins and Lightnin’ next to Mance Lipscomb and next thing I knew he was playing stuff I’d been trying to sort out for years. The original idea of Justin going to Chicago (besides just keeping an eye on him) was that he would take a few classes at the Old Town School, but within a few weeks he was TEACHING fingerstyle guitar. By the time I completed my eight-week course and returned home Justin had turned 18 and elected to remain behind.

He was back in Nashville six months later and, musically, things began to develop rapidly. A jug band, a rock band, a short stint as a Duke, but, lo and behold he’d begun to come up with songs of his own and they were really fucking good. He would release eight full length albums and an EP over 13 years during which our paths crossed infrequently, usually on the road. Ironically, we both sat out the last summer of his life in Tennessee, grounded by pandemic, unable to escape to the only place either one of us ever felt at home: The Highway.

We spoke often those last few months, saw each other a handful of times and I talked to him the night he died. I am grateful for that. This record is called J.T. because he was never called anything else until he was nearly grown. Well, when he was little, I called him Cowboy. For better or worse, right or wrong, I loved Justin Townes Earle more than anything else on this earth. That being said, I made this record, like every other record I’ve ever made… for me. It was the only way I knew to say goodbye.

See you when I get there, Cowboy,

Dad.”

https://youtu.be/YaK9ZLqqHRI

https://youtu.be/4oeNX5A13Ho