It has taken me 35 years to finally look into this Roy Harper dude, a man who seems to have had a serious connection to two of the favourite bands of my youth.

It has taken me 35 years to finally look into this Roy Harper dude, a man who seems to have had a serious connection to two of the favourite bands of my youth.

Not entirely sure why it dawned on me to do this, but perhaps it’s all the photos of the eccentric British folk singer-songwriter-poet that I found while reading Bob Spitz’s biography of Led Zeppelin. Just Google “Roy Harper + 1970s” — he was like some sort of Quaaludes ‘n’ coke Where’s Waldo — hovering behind Zeppelin manager Peter Grant backstage, lounging on a fur bed with Robert Plant in the back of their jet, wearing a G-string while Robert dresses in drag in his suite at the Hyatt House (Riot House) on the Sunset Strip, recording in the studio with Jimmy Page, chatting with Bill Wyman and Jimmy at the Swan Song Records launch party, goofing around in the control room at Abbey Road with Roger Waters and David Gilmour, or walking in with the band at The Song Remains The Same film premiere. The time has finally come to listen to and find out a little more about one of only three non-band members to sing lead vocal on a Pink Floyd song (Have A Cigar), and the namesake of the final song on Led Zeppelin III — Hats Off To (Roy) Harper.

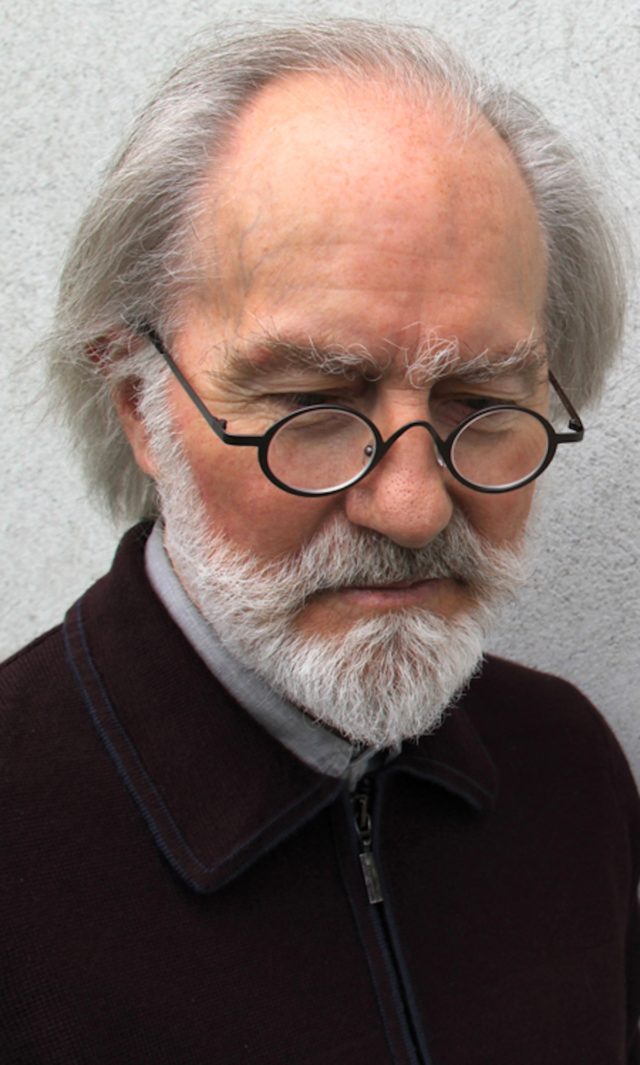

Why the hell did they dig him so much? Well, it’s because Harper — now 83 — was a supremely talented and uncompromising weirdo who didn’t kiss ass. Even the most cursory search will show you that it wasn’t just Zeppelin and Floyd who enjoyed his company. He was amongst the best-connected English musicians of all time.

It was in the mid-’60s that the Mancurian transitioned from writing poetry to playing folk music and earned a residency at Les Cousins folk music club in Soho. That’s where he first started to rub elbows with some (eventually) pretty famous colleagues like Nick Drake, John Martyn and Joni Mitchell. His Les Cousins gig landed him a record deal with Strike Records — which was run by composer Lionel Segal and accountant Adrian Jacobs. The pair also ran Go Records and a publishing company. Sadly, Strike only lasted a year, but was reactivated in 1988. His first Strike release was a 1966 single called Take Me In To Your Eyes. It’s pretty damn rare — only one pressing in the U.K. and another in the Netherlands. A clean copy will set you back hundreds. The same year, he cut an LP for Strike called Sophisticated Beggar. With the demise of Strike, Columbia Records took a gamble on Harper’s obvious talent, and signed him. They paired him with The Kinks’ producer Shel Talmy, with whom he made two albums — Come Out Fighting, Ghengis Smith (1968) and Folkjokeopus (1969). The 11-minute song Circle was enough to put Columbia off, and when he was picked up by Liberty Records for his third album, it included the 17-minute McGoohan’s Blues.

This “art-before-commercialism” approach is what endeared him to the likes of Led Zeppelin, then in the midst of fighting with Atlantic Records — who wanted to put a radio edit of Whole Lotta Love out as a single. Page and Plant met Harper at the Bath Festival in 1970. Harper’s aggressive acoustic style and abundant attitude inspired them during the making of their increasingly acoustic third album. Page and Plant had decamped to the rustic Bron-Yr-Aur cottage in Wales to relax with and write new songs. One night in the off-the-grid cottage, Page and Plant were jamming blues songs and came up with an adapted version of Bukka White’s Shake ‘Em On Down, which they renamed Hats Off To (Roy) Harper as a tribute to his talent and integrity.

The following year, Page played acoustic guitar on the track The Same Old Rock on Harper’s 1971 album Stormcock. Until the album was re-released in the ’90s, Page was credited as S. Flavius Mercurius (Latin for Yellow Mercury?) due to restrictions stemming from his contract with Atlantic.

During this time it wasn’t just Page and Plant who were influenced by Harper. He got picked up by Peter Jenner, the former manager of Pink Floyd and Syd Barrett — and signed to the same record label, Harvest. Ian Anderson of Jethro Tull cites Harper as the main influence on his guitar playing and songwriting. This doesn’t surprise me at all — listening to Harper’s music for the first time, its complex lyrical nature reminds me most of Robert Wyatt and acoustic Jethro Tull like Cheap Day Return, the first part of Thick As A Brick and Wond’ring Aloud.

Johnny Marr considers Stormcock to be a foundational British LP. Pete Townshend has long been a fan of Harper, and not only has Kate Bush covered his songs, but she’s recorded with Harper as well. Joanna Newsom is a huge fan of Stormcock and Robin Pecknold says the album was a key influence when making Fleet Foxes’ sophomore LP Helplessness Blues.

I’m not sure about Marr, but I definitely hear loads of Morrisey-like vocal phrasing in Harper’s songs. I also hear melodies which remind me of David Byrne and both instrumental and vocal passages which are really similar to stuff by Dirty Projectors, maybe even Tunng.

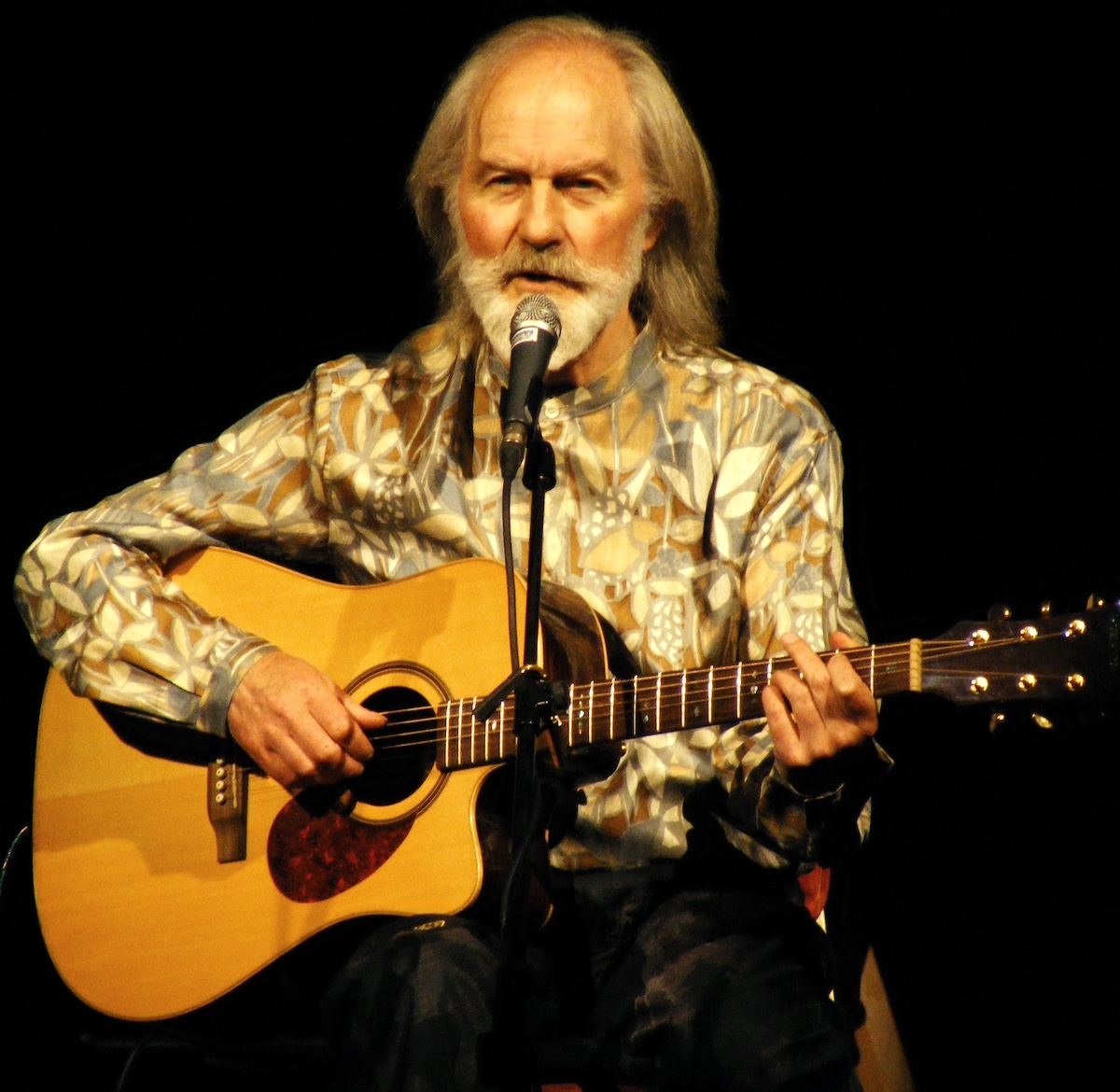

In 1973, Harper released Lifemask, with Page one again contributing guitar — on the tracks Bank Of The Dead and The Lord’s Prayer. Page plays slide guitar on Male Chauvinist Pig Blues from Harper’s 1974 album Valentine. In fact, that track is a rather star-studded affair, with The Who’s Keith Moon on percussion and Faces’ Ronnie Lane on bass. Tull’s Anderson contributes flute to the track Home.

This posse of A-listers carried over to the album release party for Valentine, held at the Rainbow Theatre on Valentine’s Day, 1974. Page joined Harper for what he calls a “memorable gig.”

“During the acoustic part of this set, I played Male Chauvinist Pig Blues,” recalls Page. “Then both Roy and I switched to electric when we played Too Many Movies and Home with the classic rhythm section of Keith Moon on drums and Ronnie Lane on bass. We rehearsed earlier that afternoon.”

Joining them was Zeppelin drummer John Bonham — who also contributed acoustic guitar, of all things. Plant was also in attendance. There are photos on Jimmy’s Facebook page (that’s fun to say).

Pink Floyd were working away on Wish You Were Here in Abbey Road‘s Studio 3 while Harper was using Studio 2 to record HQ — the followup to Valentine. Having gone a bit overboard singing Shine On You Crazy Diamond, Roger Waters wasn’t happy with the sound of his lead vocal on Have A Cigar, which he attempted afterward. David Gilmour didn’t feel the vocal was right for him, either. Word of this dilemma reached Harper next door, who decided to pop by and offer his services. Surprisingly, the Floyd agreed to let Roy belt out the lead vocal on the band’s guitar-laden skewering of the music industry. You can hear Roger’s outtake on the Immersion Box Set version of the Wish You Were Here reissue, but otherwise, Harper’s version is the famous one on the record, and undeniably great.

While Gilmour opted not to try the vocal himself, it was he who repaid the favour by appearing on the album Harper was making. Gilmour plays electric guitar on The Game. And if you think the track has a hot bass player, you’re right. It’s Zeppelin’s John Paul Jones. He’s joined by Steve Broughton on drums on the track — the only one on the record without Bill Bruford. Talk about having talented friends! Good lord.

This wasn’t the last time Gilmour and Harper would collaborate. The pair co-wrote the song Short And Sweet, which Gilmour recorded for his self-titled debut solo album in 1978. Harper had a crack at it himself on his 1980 album The Unknown Soldier. The pair performed it together during Gilmour’s run of three shows at London’s Hammersmith Odeon in 1984. You can see it in the concert film David Gilmour Live. That same year, Harper helped his mate out with backing vocals on his second solo album, About Face. Half the songs on The Unknown Soldier were co-written by Gilmour, who plays guitar all over it.

Harper’s 1977 album, Bullinamingvase, features another fairly well-known pair of musicians — Paul and Linda McCartney, who contribute backing vocals on the kinda twee One Of Those Days In England. The guitarist on the album, including that track, is none other than Henry McCullough, who was lead guitarist during the first iteration of Wings from 1972 to 1973. Jimmy McCulloch — Wings‘ current lead guitarist at the time — is also on the album. One Of Those Days In England also has a few other veteran Harper pals — Lane (Small Faces, Faces, Slim Chance) on bass and Alvin Lee (Ten Years After) on guitar. WTF?

The following year, Harper worked with Page again, helping him with lyrics and ideas for the next Led Zeppelin record. Their work was scrapped when Plant rejoined the fold, after taking a leave from the band following the death of his son. One wonders if those Zep-intended lyrics ever made their way onto a recording of his or Page’s. Perhaps they were used on the 1984 album Whatever Happened To Jugula?, which Harper made with Page. I don’t love that record as much as some of the ’70s stuff. This was around the time Jimmy was getting clean — doing The Honeydrippers with Plant, The Firm with Paul Rodgers and gearing up to perform with Led Zeppelin at Live Aid.

Jugula managed to renew interest in Harper’s career and catalog, just as a duet did a few years earlier by Kate Bush and Peter Gabriel. That’s right, in 1979 — six years before Don’t Give Up — Gabriel joined Bush on her televised Christmas special to sing Harper’s Another Day. Bush would go on to appear on The Unknown Soldier the following year, dueting with Harper on the track You. Harper appeared on Bush’s Never For Ever album that year, providing backing vocals on Breathing. The pair are well-documented mutual admirers.

Despite all the exposure that comes from a decade of attention, collaboration and dedications, Harper still struggled financially. He fought with the Harvest label (EMI) for years and started his own label in 1982 — releasing the album Work Of Heart, which the Sunday Times called the “best album of the year.” But nobody bought it. Harper lost his home in the recession of the early ’80s. He fought his way back to prominence by steadily gigging with Page under a variety of throw-away names. The pair released Jugula, Harper performed at the last Stonehenge Festival, which, like that 1984 concert with Gilmour, was released on video. The hard work led to him re-signing with EMI. He managed to launch Science Friction Records in the ’90s and obtain the rights to his entire back catalog, and now lives quite comfortably. He has continued to work with Tull and Anderson, Page, Newsom and Townshend — as well as collaborating with the likes of The Tea Party, Anathema and John Renbourn.

He was the subject of a documentary film called Man & Myth in 2013. That year, he was also charged with 10 counts of historic sexual abuse of an underage girl. He was found not guilty on two of the charges in 2015, and the rest were dropped.

Here’s a playlist for those of you who — like me — need an introduction to this fascinating creator.

• • •

Area Resident is an Ottawa-based journalist, recording artist, music collector and re-seller. Hear (and buy) his music on Bandcamp, email him HERE, follow him on Instagram and check him out on Discogs.