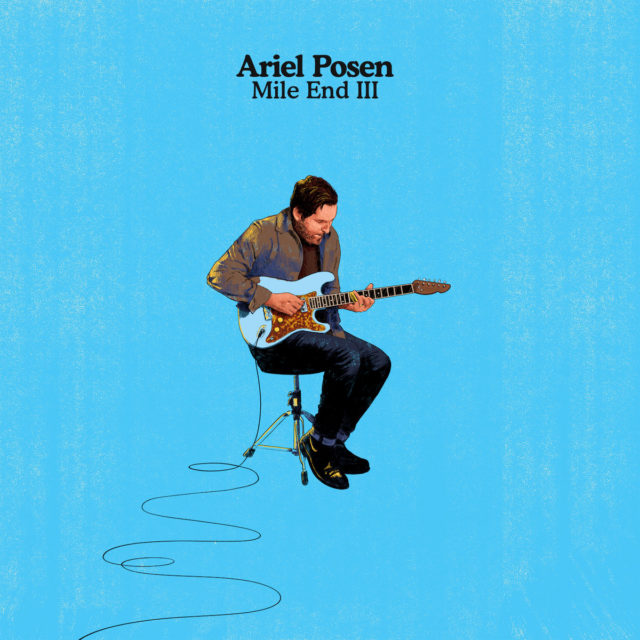

This is Ariel Posen, signing on at one-oh-one Mile End Road in Winnipeg, Manitoba, Canada.

This is Ariel Posen, signing on at one-oh-one Mile End Road in Winnipeg, Manitoba, Canada.

Much has happened since my last broadcast. Where did I leave off?

Ah yes, I went to look for the bird. And I found it. This was only after having followed it for several days. It landed in what could have been the tallest tree still standing. And there it stayed, perched on one the barkless branches at the top of it. I waited some time before climbing it. What bark remained on the tree sloughed off as I kicked and pulled my way up its lifeless bole.

When I got to the branch and the bird, I saw I was too late. Although it had remained standing, it had died.

Or so I thought. It had been years since I had seen anything alive, and in my sorrow I reached out to feel its feathers, their delicate softness, a reminder of everything that was lost since the world ended. I also expected, for it had not been so great a time that I watched it from afar, to feel some warmness, the fading memory of life on its skin, in its feathers.

But it was cold. Very cold. And hard.

I pushed asides some of the feathers and saw that its body was made of metal. Instead of a fleshy pink, it was silver coloured. Aluminum. Steel. Titanium perhaps.

The bird was a robot.

I took it with me to the base of the tree and opened it up, like a shell, hollowing it out. After about an hour, I reasoned that its battery had run dry.

It was then that a despair overwhelmed me, and I threw it to the ground in anger, stamping on it, crushing it beneath my boots.

The bird had given me hope that the world would survive. But it was a facade. A pantomime of life. A horrid, battery-powered facsimile of meaning and purpose. But the world was now meaningless and purposeless. I was a pioneer in this new world. The Un-world. This world of dead and darkness.

Tormented by this, as if I was haunted by a pack of starving dogs, by wolves, I walked aimlessly. Why return to 101 Mile End Road if it is, indeed, a dead end? What had I to live for? All was lost. All would never return.

I traced the river, ran my hands along its lazy curves, its bends. I could walk in any direction and it would all be the same. All would be reminders of what we sacrificed. Of what we killed. We made ourselves martyrs, and look at where it led: to dead trees and mechanical birds.

I don’t recall how long I let myself wallow in these thoughts, but it was the boat that knocked me out of it.

It was caught within the shallows of the lazy river, lightly banging against the rocks it had hung itself up on. It was a two-seater. The engine long ago removed. But there were paddles. And there was water. A bottle of it sat on the thin wooden bench.

I was thirsty, so I opened it, smelled its deliciousness, and drank greedily, filling my stomach with its freshness.

Someone was here, I thought, and recently.

I called out, but no one responded.

Where had they voyaged from, I wondered. And where were they going?

• • •

To read the rest of this review — and more by Steve Schmolaris — visit his website Bad Gardening Advice.

• • •

Steve Schmolaris is the founder of the Schmolaris Prize, “the most prestigious prize in all of Manitoba,” which he first awarded in 1977. Each year, he awards the prize to the best album of the year. He does not have a profession but, having come from money (his father, “the Millionaire of East Schmelkirk,” left him his fortune when he died in 1977), Steve is a patron of the arts. Inspired by the exquisite detail of a holotype, the collective intelligence of slime mold, the natural world and the suffering inherent within it — and also music (fuck, he loves music!) — Steve has long been writing reviews of Winnipeg artists’ songs and albums at his website Bad Gardening Advice, leading to the publication of a book of the same name.