I was simply walking through the forest, as I often do — ducking under splayed fir branches, weaving around old decaying birch trees pocked with outgrowths of polypore conks, climbing up and down steeply angled rock faces blanketed in soft and delicate feather mosses — minding my own business. The autumn air had brought its chill, a crisp freshness, and so I wore my brown leather jacket — the leather had begun to peel, as if it (or I) had mange, hair matted among the baldness.

I was simply walking through the forest, as I often do — ducking under splayed fir branches, weaving around old decaying birch trees pocked with outgrowths of polypore conks, climbing up and down steeply angled rock faces blanketed in soft and delicate feather mosses — minding my own business. The autumn air had brought its chill, a crisp freshness, and so I wore my brown leather jacket — the leather had begun to peel, as if it (or I) had mange, hair matted among the baldness.

I came across a couple of bones, jointed with cartilage and dried (but still pliable) flesh, and I kneeled down to prod it with a pencil. There were small maggots writhing under a flap I lifted up. I was looking at a leg, that much was obvious, but as to what part of the leg (and to what species it had once belonged to), I was uncertain. Cell service was spotty, but I managed to bring up a picture of the skeletal anatomy of a deer, and, sure enough, that’s what it was: I was looking at an ankle, where the tarsus and fibula meet with the talus and calcaneus.

Lost in this rather gruesome exploration — it smelled terrible, like rotting meat, which I guess was exactly what it was — I didn’t hear that two hikers had come into the area. They stayed on the other side of a thick clump of willows, and, at first, they didn’t notice me either. Until I stood up, and heard, beneath my foot, the snap of a twig.

In the forest, things sound louder than they should. A squirrel rummaging through a leaf pile to find the entrance to their cache can, at times, sound like a small angry bear. The forest — in its quietude, in its solitariness — amplifies its sounds. And so when I stepped on that twig, I instantly knew that whoever was there heard it, too. And so I crawled behind a large boulder to hide. More twigs broke.

“What was that?” one of them said, a woman.

“You heard it, too?” replied the other, a man.

“Let’s go. Please. It sounded big.”

“I saw it — it WAS big. Looked like a bigfoot.”

“Shut up — that’s not funny.”

“I’m serious, baby.”

“Baby?”

“What?”

“You called me baby.”

“Sorry, that was an accident. I meant ‘Kolby.’ “

“Accident.”

“I’ve heard there are bigfoots around here.”

“Can we go, please.”

“Go where?”

“Back to the cabin.”

“The cabin…”

“To get a weapon or something.”

“A weapon? What, like a kitchen knife? What good will a kitchen knife do if we get attacked by a bigfoot?”

“It’s not a bigfoot.”

“Still.”

“I’ll get… I don’t know… the tire iron from the car. Or the jack.”

“You’re going to kill a bigfoot with a car jack?”

“I didn’t say kill.”

“Baby…”

“You did it again.”

“Kolby.”

“You going to wrestle the bigfoot, is that it?”

“Pile drive bigfoot right on his big head, kick him in his big ass.”

“Let’s go.”

“Alright, alright. Which way’s back?”

“Right there, we went around that stump.”

Silence.

“You know it wasn’t an accident.”

“I know.”

Needless to say, I followed them.

• • •

To read the rest of this review — and more by Steve Schmolaris — visit his website Bad Gardening Advice.

• • •

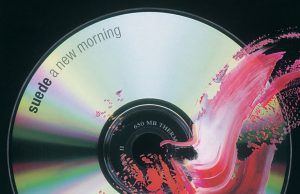

Steve Schmolaris is the founder of the Schmolaris Prize, “the most prestigious prize in all of Manitoba,” which he first awarded in 1977. Each year, he awards the prize to the best album of the year. He does not have a profession but, having come from money (his father, “the Millionaire of East Schmelkirk,” left him his fortune when he died in 1977), Steve is a patron of the arts. Inspired by the exquisite detail of a holotype, the collective intelligence of slime mold, the natural world and the suffering inherent within it — and also music (fuck, he loves music!) — Steve has long been writing reviews of Winnipeg artists’ songs and albums at his website Bad Gardening Advice, leading to the publication of a book of the same name.