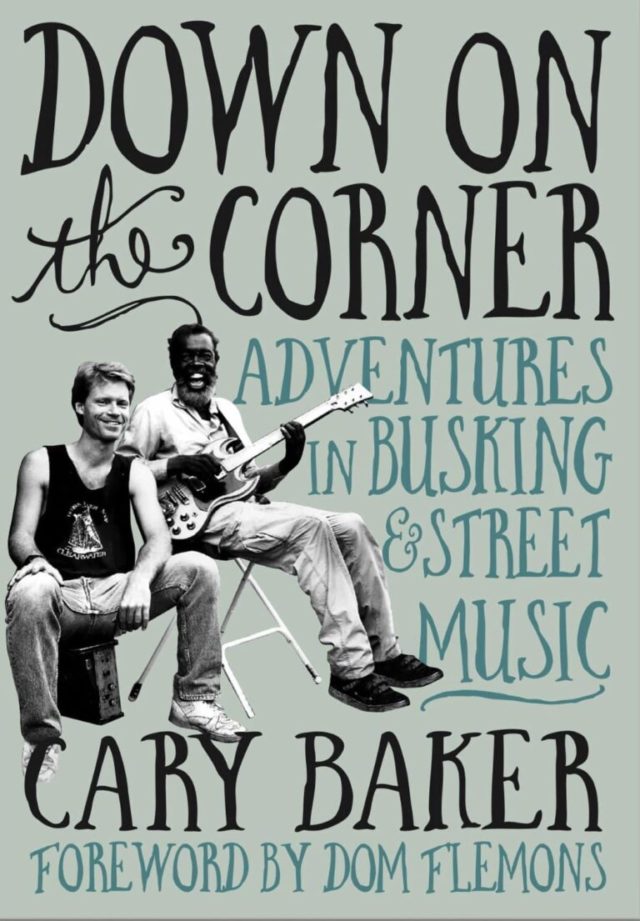

Tired of ghost-written music memoirs and fawning bios? Had enough of deep-dive discographies? Bored with overpriced coffee-table tomes? Looking for something new and interesting to read? I have just the thing: Cary Baker’s inspired new non-fiction number Down On The Corner: Adventures In Busking And Street Music. Far as I’m concerned, the title tells you what you need to know. But if you’d like a little more info on the book and Baker, the press release is below. And below that is a chapter on Tymon Dogg that Cary was nice enough to let me run in advance. Enjoy. Then go pre-order the book HERE.

THE EDITED PRESS RELEASE: Anyone who has lived in or travelled through a city has encountered street musicians. Singers, often accompanying themselves on guitar or other instruments, playing the sidewalks, parks and subway stations. Perhaps you’ve tossed a quarter, or a dollar bill, or even $5 into the tip jar or open guitar case. But did you ever wonder who these people are — why they opted to make the streets their stage, and whether if any of them had gone on to make it in the music industry? Some of them — Lucinda Williams, Billy Bragg, Violent Femmes — became international stars; others settled into the curbs, sidewalks, and subway stations as their workplace for the duration of their careers.

Drawing on years of interviews and eyewitness accounts, Down On The Corner: Adventures In Busking And Street Music — due Nov. 12 — explores street singers in a myriad of musical genres, from folk to rock ’n’ roll, blues to bluegrass, doo-wop to indie rock. Author Cary Baker also surveys busking hotspots like New Orleans’ French Quarter, Chicago’s Maxwell Street, New York’s Washington Square, San Francisco’s Fisherman’s Wharf and London’s Tube, to name a few.

Baker explains his love of street music: “One day around 1970, my father said he’d like to take me to Maxwell Street Market, an open-air flea market adjacent to Downtown Chicago… The first thing I heard, long before I could see where it was coming from, was the sound of a slide guitar — not just any guitar but a National steel resonator guitar. We followed the music and found ourselves standing on the west side of Halsted Street, midway between Roosevelt and Maxwell, where Blind Arvella Gray was playing the folk/blues song John Henry — a song that seemed to have no beginning and no end. In that moment, I developed a lifelong affinity for the informality, spontaneity, and audience participation of busking.”

Baker began his writing career at age 16 with a feature about Gray for the Chicago Reader. The longtime Californian’s return to writing follows a 42-year hiatus in L.A., where he directed publicity for six labels (including Capitol and I.R.S.) and two of his own companies, working with acclaimed artists and labels such as R.E.M., Bonnie Raitt, Smithereens, James McMurtry, Mavericks, Bobby Rush, Willie Nile, and Omnivore Recordings.

Tymon Dogg: Fiddling, Strumming and Clashing

British musician Tymon Dogg, whose given name is Stephen Murray, is known for his versatility. He is proficient with various instruments including violin, guitar, and piano, and has been associated with varied musical genres, from folk to punk-rock. His influences are mainly American singer songwriters: Woody Guthrie, Paul Simon, Leonard Cohen, Bob Dylan and Randy Newman.

Tymon (which rhymes with Simon) gained recognition for his collaboration with The Clash during the late 1970s and early 1980s. He contributed violin and songwriting to several songs on the band’s 1980 album Sandinista! album, for which he wrote the track Lose My Skin, a showcase for his high-pitched lead vocals and violin.

Throughout his career, Dogg has also released eight solo albums and worked on various music projects, from a single (under the name of Timon) to unreleased tracks for The Beatles’ Apple Records with Peter Asher producing, Paul McCartney on piano, and James Taylor on guitar. He also toured with The Moody Blues, whose frontman Justin Hayward produced a second Timon single.

Not many artists take to street singing after they’ve played world-class venues, nor after they’ve gone into the studio with a Beatle. But for Dogg, it came down a simple matter of economics. “The first time I actually I was ever played in London was actually at the Albert Hall, supporting The Moody Blues,” he says with a sigh. “And after I’d done a nationwide tour in all these massive places. I didn’t really have much money because we were, after all, the support act. You get your money and it’s immediately spent on hotels, and gone after a few months. So I thought, ‘I’ll just go out [on the streets] and play some songs.’

“I was always quite romantic about busking. I got down to the south of France when I was 15. And I played around Avignon and San Tropez. I ended up in Nice, working there for a long time on the on the Promenade, and I made quite good money, a lot of money — in today’s money, it was like 100 or 200 pounds. At night, I’d play for an hour and a half, two hours — they’d be tourists coming by. And so I always had [busking] as my ammunition, as it were. It’s a great way [to perform] if you if you need independence, and you want to work on something.”

Around 1971, Dogg was renting part of a house along London’s Westbourne Grove and met John Graham Mellor, who would soon come to be known as Joe Strummer. He was an art student at London’s Center School of Art. “And [Joe] was getting a bit fed up, you know, because this may have been art school but it was school. And he needed money. So he was thinking, ‘I’ll come out with some hang out with Tymon to get some money.’ ”

That was around the time Dogg decided to take up violin. “I learned an instrument I’ve never played before,” he says. “Because I thought if I was going to be standing there — totally ignored by people mostly — by the end of that two hours or whatever, three hours, at least I’m going to be a little bit better at this. If you play any instrument, two hours a day, something’s going to start happening. So [Joe] decided to take up the guitar. And I had a guitar. He was left-handed, but I only had my right-handed guitar. So he was playing that and he would learn the chords, to back up my playing the violin. We’re basically standing in London learning our instruments — and we got to be pretty good pretty quickly. I got OK on the violin. And he, of course, became Joe Strummer!” This was a full five years ahead of formation of The Clash.

The busking life threw Strummer and Dogg their share of setbacks. According to Dogg, “We got we got locked up a few times. We got deported from Holland once. We had some very interesting times. But the great thing about Joe is he was always a real optimist. He was just hanging out; his spirit was very much in songwriting. We’d play games: We’d be busking, and we’d say ‘Hey, let’s see who can lean back the furthest without falling over while we’re playing our instruments!’

“We had some fantastic times. Joe was very funny because he had a baritone voice, which is much lower than mine — mine is more the tenor/alto area — and it was bloody loud. So I’d be singing the song, and there’d be this fog-horning in my ear. At one point, I said to him, ‘Listen, why don’t you stay here and I’ll go and play somewhere else. That way, we have two places going at once!’ ”

Public performance laws caught up with Dogg and Strummer in Holland. Dogg explains: ”We got to Amsterdam to play some good paying gigs. I suggested we busk down the street and get a bit of money so we could go to a restaurant. Police came and were in plainclothes and said, ‘You’re under arrest,’ and they took the instruments. So we had no instruments for the gig. Joe went off and came back with a violin. It was some person’s family heirloom — it was it was some old precious violin that some kid sneaked out of his mother’s house.”

At some point, the Strummer/Dogg duo went their separate ways. “I was ready to do my own show,” Dogg says, “So there I was in Green Park, and he walked away. That’s when he started his career. But really, it was great to work with a partner like him. Because he was optimistic. He made the best of everything.”

Strummer, of course, went on to form The Clash with Mick Jones, Paul Simonon and Topper Heddon. And Dogg pursued his own career. In addition to releasing eight solo albums between 1976 and 2025, Dogg has played on and/or produced albums by Ian Hunter, Ellen Foley, Poison Girls, El Doghouse and Susannah Austin, as well as The Clash and Strummer’s post-Clash band, The Mescaleros.

The parting of Strummer and Dogg augured the end of Dogg’s tenure as street singer. “I didn’t busk after that, really” he says. But he credits his outdoor performances for helping him learn to project his singing. “We just had to be loud, as we were drowned out, whether it was by traffic or something. We were in train stations quite a lot. If we were inside the Tube, we had a nice echo. So that would help particularly with an instrument like violin, which had a lot of sound to it.”

Dogg hasn’t ruled out a return to the streets in the future, regarding it as something he can always turn to when he wants to refine new songs and new sounds. “I was thinking to do some busking again, actually. Maybe I’ll even work with somebody who plays classical,” he says. “It’s a great thing when maybe you haven’t got any work or you’re not getting any shows in clubs. It’s a really great way to just keep on going. You can be making money while you’re actually rehearsing. But mainly you’re just playing and you’re having a good time. If you’re not doing that, it’s hard work.”