THE EDITED PRESS RELEASE: “D-Settlement were Chicago’s best-kept secret: A trailblazing, diverse band mixing R&B, soul, punk, gospel and funk with biting wit and political commentary.

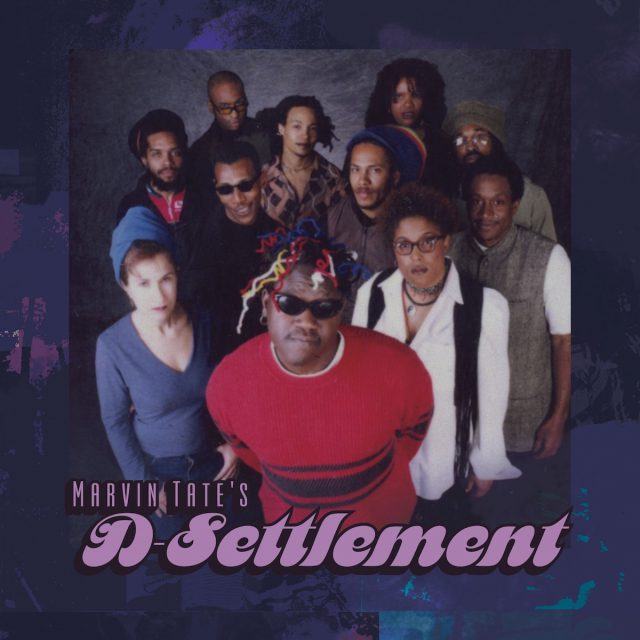

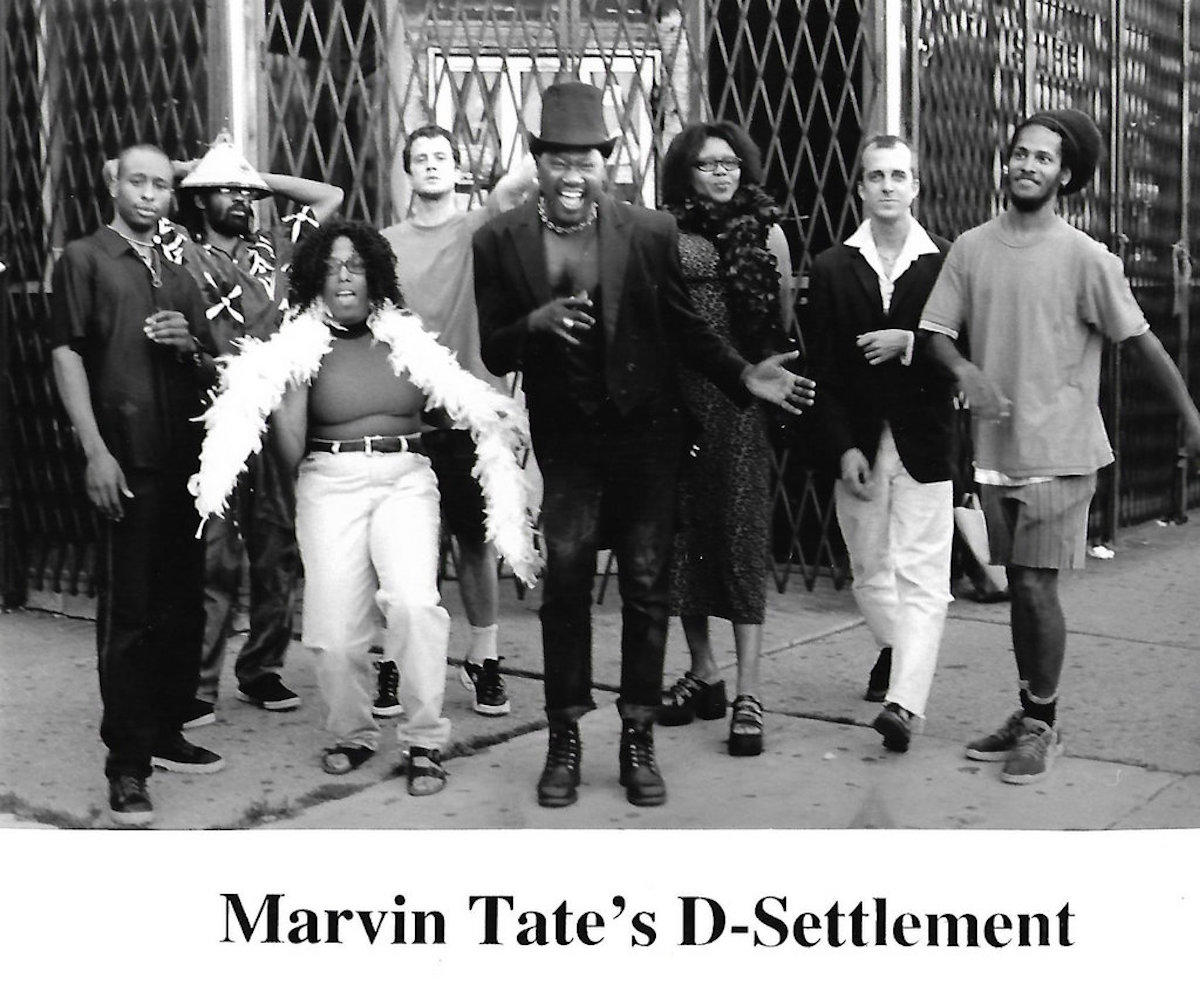

Led by Marvin Tate — a poet, artist, playwright and raconteur who wore pipe cleaners in his hair — and supported by a large, dynamic cast of characters, their music was both of and ahead of its time. From the 1990s to 2003, across three self-released albums — Partly Cloudy, The Minstrel Show and American Icons — D-Settlement told Tate’s nuanced stories about transgender rights, gun violence, systemic inequity and gentrification from an unapologetically Black perspective, drawing from his life in and around Chicago’s West Side. Their music grew to encompass Americana, opera, cabaret and theatre, intersecting in ways that only Tate could conceive. Their concerts brought these influences to bear so often, and with such force, that stealing the show was a matter of routine. Their creative vision left imprints on people like Angel Bat Dawid, Ben LaMar Gay, Theaster Gates, Avery R. Young and Angel Olsen, relating traumatic experiences, skewering organized government, religion, corruption and poverty, and imagining better futures through an Afrofuturist lens. But record labels didn’t know how to handle such pathbreaking work. Twenty-plus years on, American Dreams’ reissue, Marvin Tate’s D-Settlement, is the music’s worldwide release.

Tate began D-Settlement at the center of Chicago’s vibrant spoken-word scene. He began performing slam poetry in the mid-’80s; by 1990, he was Chicago’s poetry slam champion, and in ’94 won a poetry slam presented by Lollapalooza. At the same time, he began incorporating his work within a musical context, performing with jazz luminaries Jeff Parker and LeRoy Bach in the band Uptighty, which morphed into an early version of D-Settlement. Tate’s poetry and lyrics are arresting, plainspoken, and often darkly funny, equal parts Gwendolyn Brooks, Richey Edwards and Ivor Cutler, able to inhabit characters all over the underclass. He’s an aggrieved poet reflecting on the indignities of reading poetry to a majority-white audience: “This shit went over well with the brothers from Omega last week: ‘Kill Whitey, Whitey did it! Went to the moon and fucked an alien. Whitey, Whitey, Whitey…’” He’s a churchgoer telling off organized religion on “Trouble A Come”: “Daddy was a preacher man / He loved the choir singers / He’d meet them ‘hind the pulpit / They played underneath their robes and…”

Tate developed his ability to inhabit such diverse characters as a child, playing the dozens at school, reciting We Real Cool to a rapt playground, and telling stories to his brother Melvin and cousin Jerome in a storytelling group called The Kooky Boys. Tate and his five siblings, raised by their single mother, grew up without radio or television; they’d take out a box and make up TV shows. In 1969, when he was nine, his mom was shot in front of him. “This dude had a silver gun and he said, ‘You let that bitch kick your ass, man?’ I was helping my mom fight. My mom pushed me out the way, and the dude shot at her.” His characters include children missing a father figure and adults grieving family members lost to heroin addiction; they span the breadth of human emotion, and they’re fiercely independent.

D-Settlement brought these stories into view with kaleidoscopic arrangements inflected with their members’ varied skillsets: guitarist and vocalist George Blaise, bassist and vocalist Olin Langley, singers Tina Howell and Renee Ruffin, drummers George Jones, Virus X, David Hilliard and Debi Buzil, multi-instrumentalists Adam Conway and CJ Bani. Conway talked himself into the band, variously wearing singer, drummer, producer, engineer and accountant hats; Ruffin became adept at imitating flutes and birds; Blaise and Langley often spearheaded arrangements and production. All hands were always on deck. On Partly Cloudy, the band’s music serves as a foil to Tate’s poetry: raucous funk (Turn Da Fuckin’ Lights Back On, Charlie of Washington Square), reggae (Who Sold Soul?), slow-burn piano blues balladry (Insomnia in NYC, Marching in the Mist). The game-changer is Tate’s elastic, incisive voice, which raps, pleads, soars, crackles with a preacher’s fire. Over the course of their discography, Tate works more and more as a bandleader, directing his multifaceted ensemble through stunning performances with heavy melodic interplay, whether imbued with Afrofuturism (Brown Eyes (Miss D), Planet D-Settlement) or stark confrontations of racism (Have You Ever Seen?, Hangman, Jury Duty).

Among the band’s strongest songs are true-to-life. The Ballad of Corey Dykes is a potent example of D-Settlement at its most provocative: Atop a gritty, funky rhythm section and backing vocals evocative of gospel, Tate spins a yarn about a 14-year-old student who shoots his teacher. “There was a real Corey Dykes,” Tate says. “I was a teacher on the West Side, man. And this young man just bullied everybody, man. And one day he said, ‘Man, I kill you.’ I just blew him off. Charged and shit. But you can never tell what youth will do. You know? Young men had no idea of what loss was, what the boundaries were, you know, and so I tried to recreate that classroom scene, because, oh, there’s some other 14-year-old Corey — that’s the narrator.”

Gerald shows a neighborhood struggling to accept a transgender child — at a time when there was scarcely a Transgender Day of Remembrance. “We’re doing songs about a young transgender person before it was fucking cool to talk about it,” says Blaise. “This was our community.” Other songs provide sardonic social critiques a la Ida B. Wells or Jane Addams. Governmental Wolf critiques gentrification, redlining and systemic racism; Turn Da Fuckin’ Lights Back On police violence, Com-Ed corruption and systemic poverty (“Somebody tell me honestly, do you think po’ people dig living like this?”). The soulful closing track A Great Day (in the Neighborhood) synthesizes all these threads, building stories of community members to a stirring crescendo pocked with police sirens, birdsong and their surroundings.

D-Settlement gave countless concerts in Chicago, pursuing their cause with an intensity reminiscent of Black Flag, sometimes getting banned from the venues they played. They regularly blew the roof off of The HotHouse, where they maintained a residency, and supported Antibalas, Ken Nordine and Bernie Worrell, garnering rave reviews from the Chicago Tribune. They were primed to break out beyond the city. But their rising star coincided with the pressures of the internet, and in 2003, as the band reached its apex, it disbanded. Tate’s creativity has bloomed since then: he’s published poetry books and performed poetry on HBO, made music with Angel Olsen, Tim Kinsella, LeRoy Bach and countless others, directed plays and musicals, quietly pursued a personal sculptural practice. But he’s done it all under the radar, without the fanfare accorded to those he’s influenced. It’s time to give him and D-Settlement their flowers.”