I never really understood the passion for mono until I read about and heard those Beatles remasters from 2014.

I never really understood the passion for mono until I read about and heard those Beatles remasters from 2014.

There’s just something to be said for hearing music the way it was intended. If you don’t know, The Beatles themselves sat in on the mixing sessions for their records — but only the mono mixes. Back then in pre-1968, that’s the equipment most people had, so those mixes were given the primary and greatest attention. The engineering, and even the recordings themselves, were done with a mono record in mind. So things were done differently — the choice and placement of mics, the amount of effects added to the music, the attention paid to keeping vocal and instrumental performances in proper unison, etc. Because unlike stereo, you can’t pan things around — things have to be closer or farther, tighter or broader.

It’s an art and a science, if you come at it as a novice who has only ever used Garageband and places instruments across the left-to-right spectrum like furniture in a Sims floorplan.

Those Beatles albums up to and including Magical Mystery Tour were recorded and mixed for mono. There are, of course, stereo versions. In fact, they’re way more prevalent because in the ensuing years, stereo has become the standard. But, back in the mid-’60s, those stereo mixes were an afterthought. The Beatles, for example, were present in the booth for the mono mixes but probably never heard the stereo mixes until after the record came out. Perhaps wondering why the bass was only in the left channel, or the lead guitar in the right — really loud.

It really seems, unlike mono, the engineers and producers didn’t have a full understanding of how to make the most of what stereo had to offer. If they had, it probably would have been recorded differently.

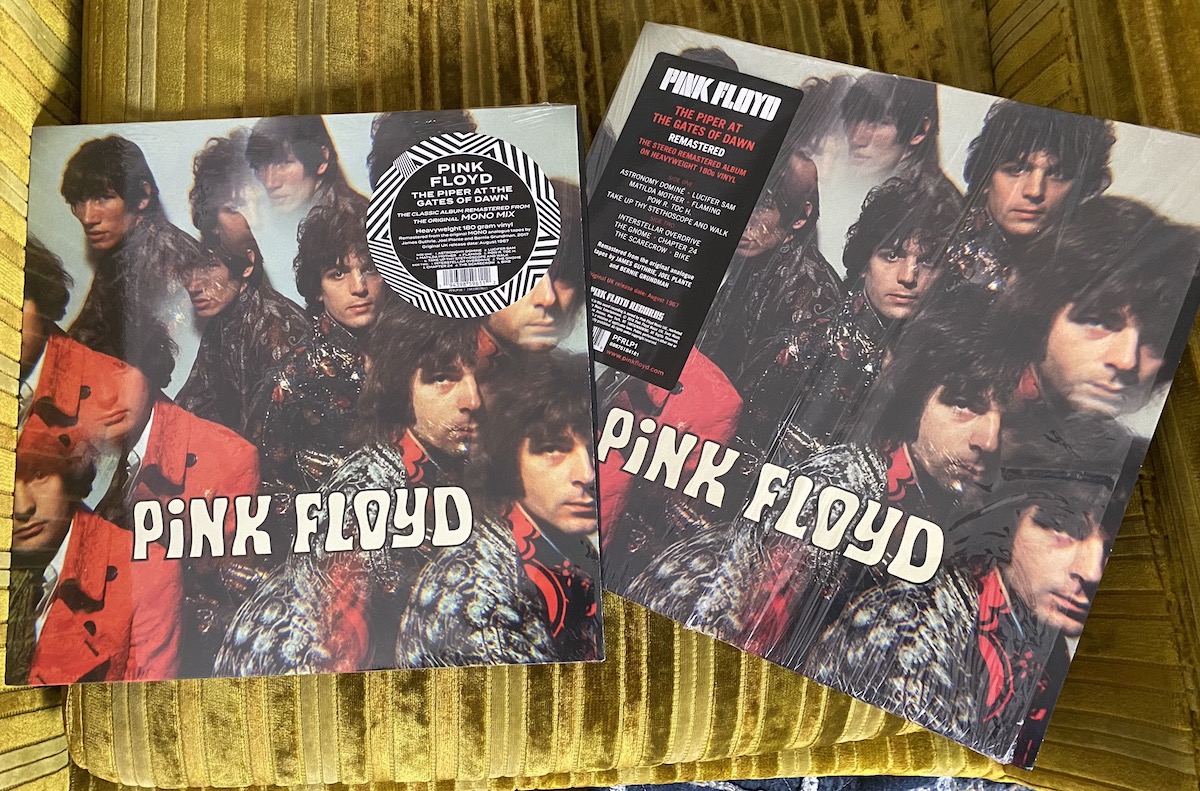

So, enter Pink Floyd‘s first album Piper At The Gates Of Dawn — just re-released in remastered mono by the same folks who did the remastered stereo version in 2016. The mono remaster was done in 2017, but released in limited format as a 2018 Record Store Day exclusive. One of those will cost you $120 now via Discogs or whatever. The new one is just over $30. The U.K. mono original, by the way, can cost more than $2,000 in great shape.

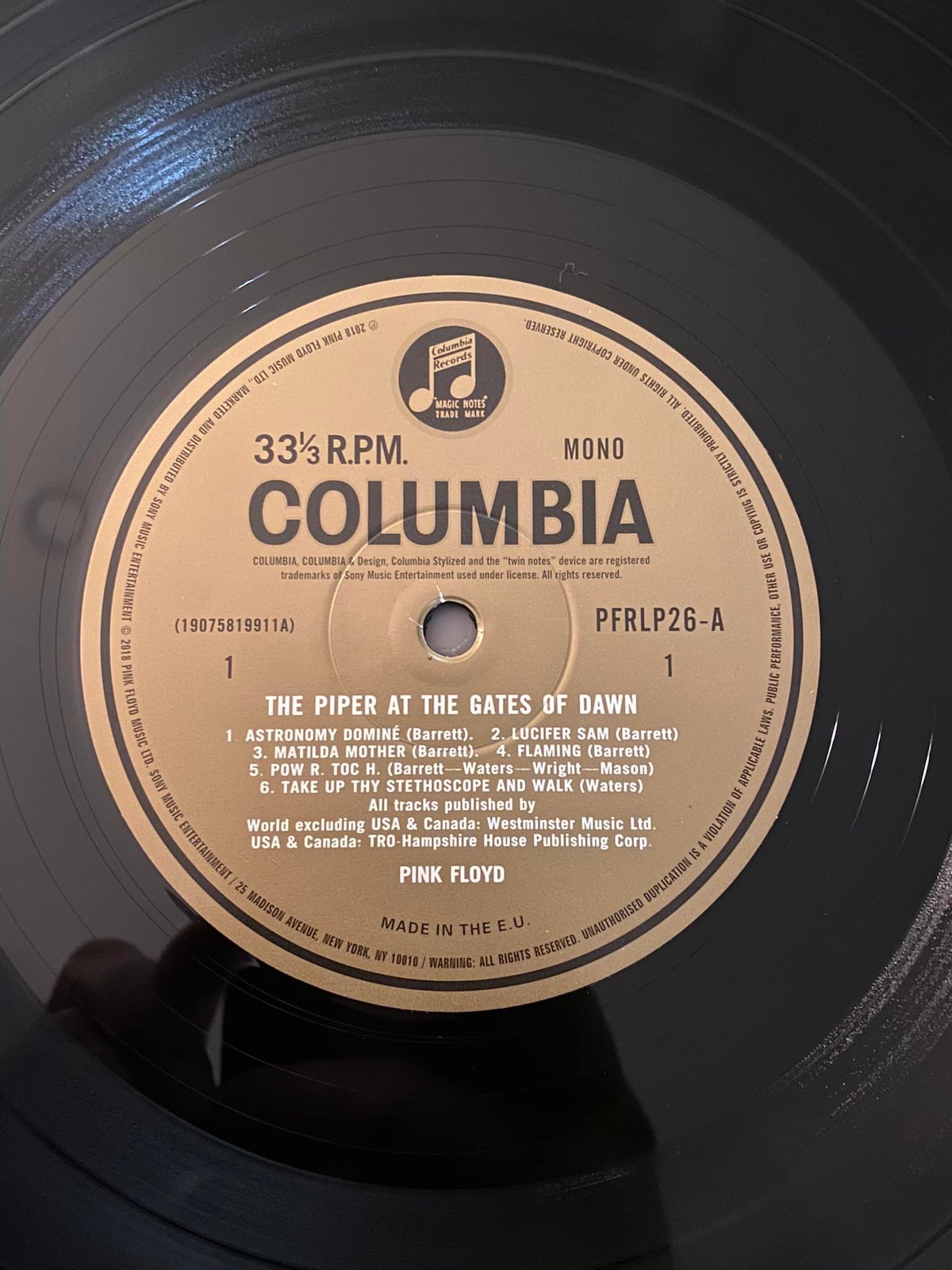

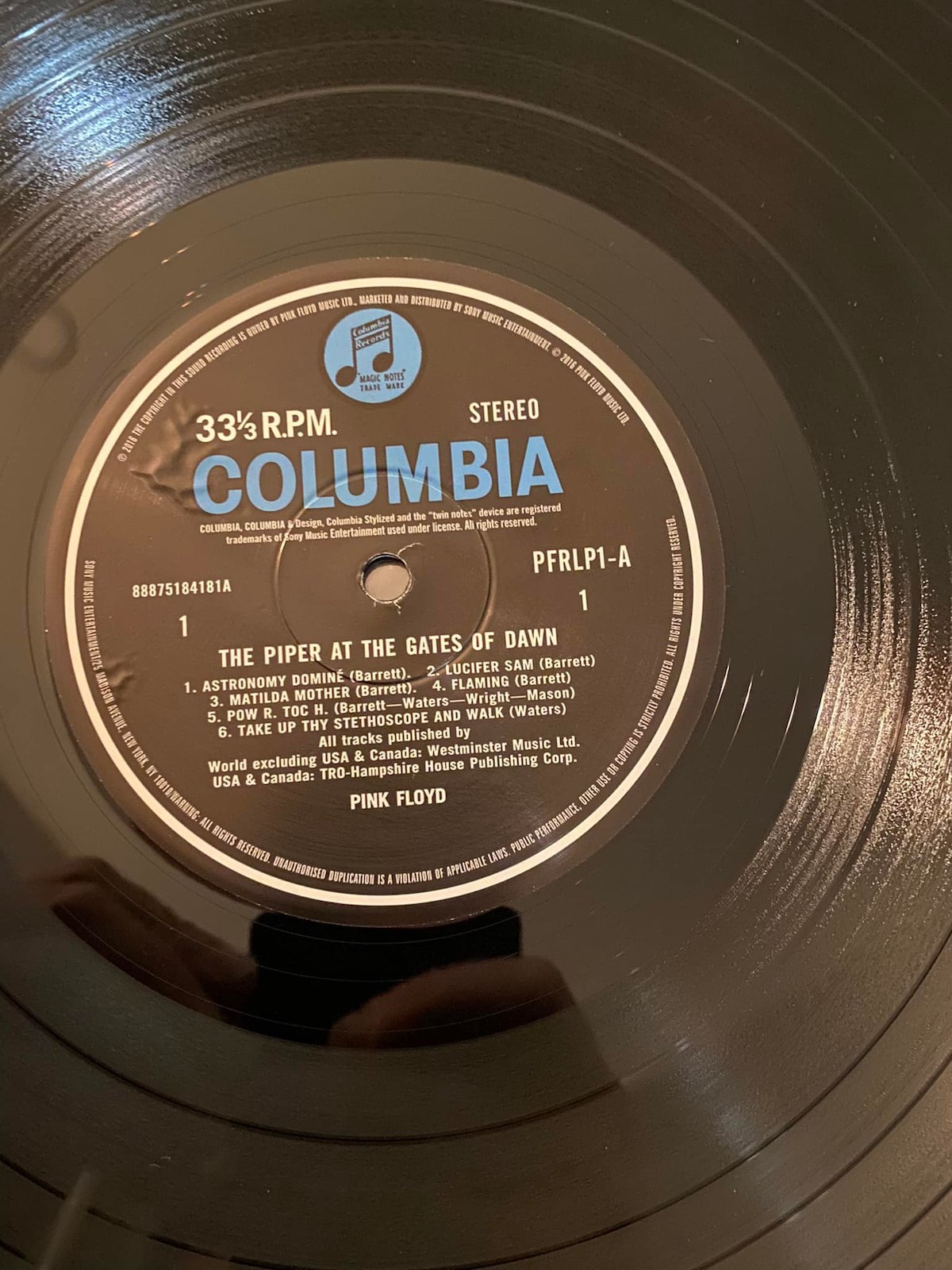

I already have the stereo remaster ($28). I picked up the new mono remaster two weeks ago and decided to compare them. My mono copy is the EU edition and the stereo is U.S., but they are essentially identical, apart from the catalog numbers and the fact that the EU one has gold labels and the U.S. has black ones. Both have lovely jackets and archival sleeves to replicate the originals, with Syd Barrett’s back-cover illustration.

The stereo version really does seem like an afterthought. Clearly more thought and work went into the mono mix. There’s a lot going on both in and with these tracks, and they don’t sound busy at all. Props to producer Norman ‘Normal’ Smith (as John Lennon called him) and engineer Pete Bown. They used their skills to make all the instruments, sound effects and vocals fit and thrive in the mono universe — even when seeped in more echo and reverb than any other Floyd album.

Even though Smith was an engineer for The Beatles for many years, they purposefully used non-Beatle mics for these sessions, so the Floyd would sound “different.”

Both the stereo and mono remasters use the original tapes as source material. I don’t know if they went back to square one or used the original mixes. I suspect the latter. Anyway, all this was done — for both the stereo and mono remasters — by James Guthrie, Joel Plante and Bernie Grundman. Guthrie has been Floyd’s producer since 1978.

The mono version has more punch and attack, but isn’t as bassy. Flaming really sounds better in mono. It’s a better mix — you can hear the vocals better. I listened to the stereo version first and really thought there was no way Pow R. Toc H. was going to be better in mono — but it is. Especially the toms and again, the goofy vocalizing at the end. Even Astronomy Dominé is better in mono because the stereo mix just has too much fading. It seems excessive and doesn’t enhance anything.

Worse, Matilda Mother is an awful stereo mix. Sometimes there’s nothing coming out of the left side. What a waste. Stereo mixes of recordings done with mono in mind need a rethink. It’s all about placement, not movement. The only thing that should have movement is the sound effects. This is why some quadraphonic mixes work and others don’t. The best ones are the ones that go back to square one and make the most of the expanded spectrum. (Like Sly & the Family Stone’s Greatest Hits, for example.)

The coolest thing about this pair: I was very familiar with the stereo mix. The mono is not just mono, it’s a different mix. Songs fade differently, some bits are more prominent and some bits are tucked back. I like it better, and it’s what was originally crafted. But I’ll keep them both.

And, seeing as I mentioned “pair” — unless you’re a collection completionist, don’t get 1973’s Harvest re-issue A Nice Pair as your sole copy of this album (or Saucerful Of Secrets). The Floyd dickheadery put the 1969 live version of Astronomy Dominé on it instead of the Barrett version. Also, Interstellar Overdrive fades early and you get no segue between it and The Gnome. Early versions had the single mix of Flaming in mono. This was corrected on later pressings. Maybe it was issued solely as a cash-grab double LP to capitalize (Capitolize?) on the popularity of Dark Side Of The Moon. For the same reason, they reissued Barrett’s two solo albums as a single set in 1974.

Bottom line: It’s cool to have both versions, but the mono is better. Nothing else sounds like this record.

Hey ho, here we go

Ever so high

• • •

Area Resident is an Ottawa-based journalist, recording artist, music collector and re-seller. Hear (and buy) his music on Bandcamp, email him HERE, follow him on Instagram and check him out on Discogs.