THE EDITED PRESS RELEASE: “Gus Fairbairn, aka Alabaster DePlume, has a pocketful of phrases that he uses all the time whether he’s walking down the street or holding court with musicians and an audience. For a long time the Mancunian would tell anyone who’d listen that they were doing very well. More recently, it’s another phrase which has a similar effect and which belies his unwavering commitment to personal vulnerability and collective politics: “Don’t forget you’re precious.”

A process that is people-first not product-first ensures that the music is unique; often gem-like. DePlume’s songs are built on sonorous circular melodies and luminous tones that transmit calmness and generosity in warm waves — unless they’re raging against complacency and the everyday inhumanity of end-times capitalism. Most importantly, he brings a valuable transparency to his work. “This is what I’m really doing,” he says. “I want to talk about why I’m doing this, and how I’m doing this.”

His double album Gold was recorded at London’s Total Refreshment Centre over two weeks. He invited a different set of musicians each day, playing the tunes to click so that DePlume, who also produced it, could cut the 17 hours of sessions together like a collage. As with all his sessions, he ensured that the musicians didn’t have enough time to rehearse the tunes, instead requiring them to tune into each other and to rely on each other to reach the end of a song. There was another rule: no listening back to sessions after recording. “The method is part of the mission,” he says. “It wasn’t like school. We had mayhem. We were having fun. That is the story and the process — and I want to live that way.”

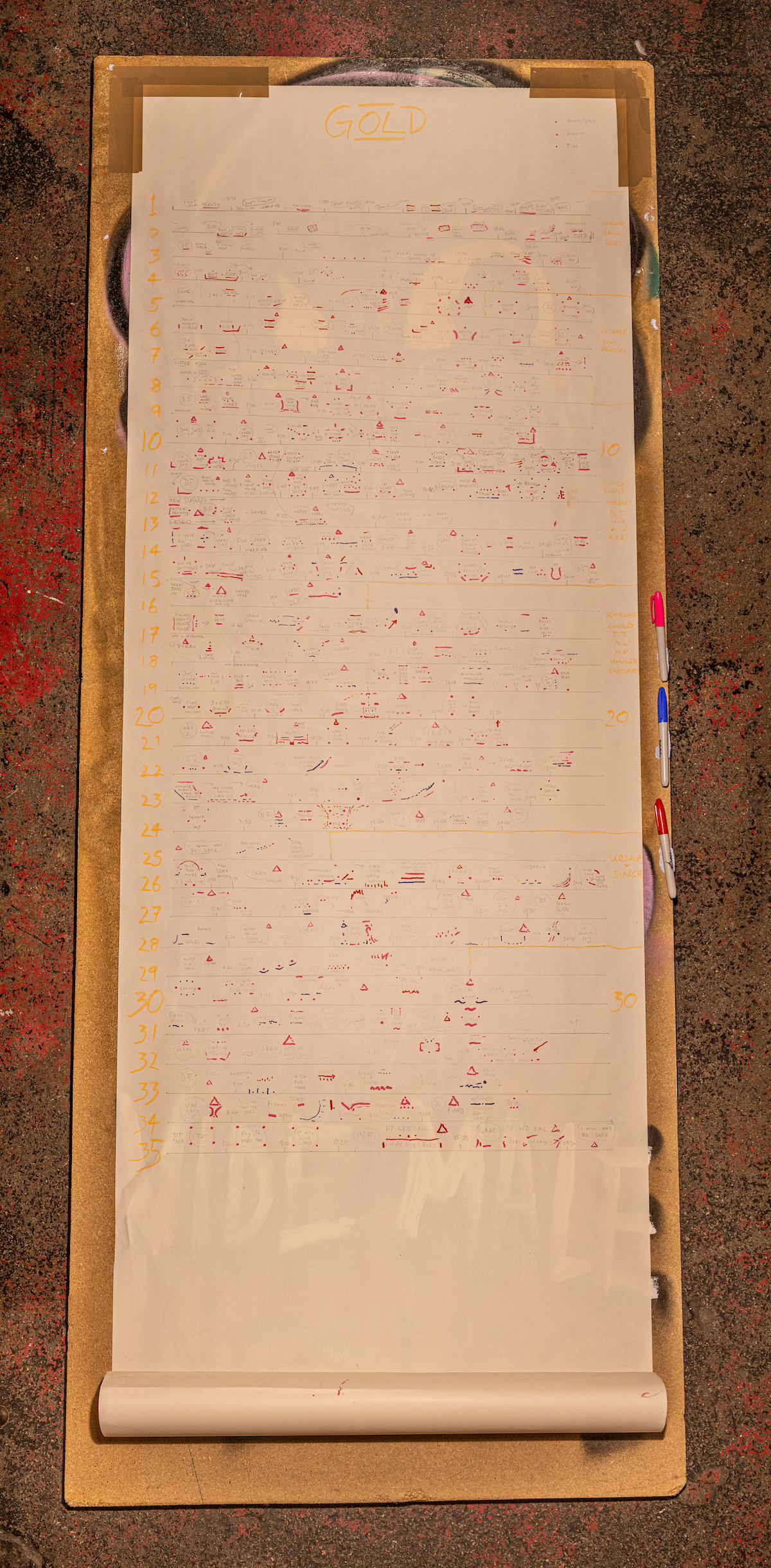

Afterwards, he made a map of what had been recorded on a long scroll of paper (right), with colour-coded lines representing each analog tape. The triangles, dots and colours shaped what emerged. The map has since been requisitioned for a gallery exhibition, and a photograph appears on the Gold album artwork. “One of the things that’s key to my practice is destroying the idea of correct,” says the poet-performer, who plays the saxophone out of the side of his mouth. “When I was a teenager I made a rock band and nothing was in 4/4,” he says. “Eventually I hammered out the tendency to four. I do it in the way it’s not usually done.”

Afterwards, he made a map of what had been recorded on a long scroll of paper (right), with colour-coded lines representing each analog tape. The triangles, dots and colours shaped what emerged. The map has since been requisitioned for a gallery exhibition, and a photograph appears on the Gold album artwork. “One of the things that’s key to my practice is destroying the idea of correct,” says the poet-performer, who plays the saxophone out of the side of his mouth. “When I was a teenager I made a rock band and nothing was in 4/4,” he says. “Eventually I hammered out the tendency to four. I do it in the way it’s not usually done.”

What’s true for the music is true for everything in his artistic practice. It applies to the offbeat way he organises musicians and audiences as much as it applies to the way he lives his life and expresses life through his songs. After his teenage rock bands, he made ‘very precise loud shouting angular rock’ until the mid-2000s when he inhabited a new iteration of himself: ‘a drunk man who travelled the U.K. and Ireland telling poems.’ Returning to Manchester, he moved into a Georgian manor house in the south of the city full of ‘chaotic guitarists’ and a collectively augmented outlook where one house became known as Iron Mountain and another Dark Cottage. It was a time full of ‘piratey, survival gigs’ and many hours of front-room jams. “I learned to play saxophone by getting drunk every night and playing music for fun with them,” he says. “This method of learning the instrument allowed me to learn to play it in an unusual way.” He became an accidental accompanist and travelled throughout Europe and the U.S. with fellow Mancunian Liz Green. “She sang very quietly,” he says. “I learned to play underneath her voice.”

He also worked for 10 years helping adults with learning difficulties enjoy socialising. He’d do this by getting them out to dance with their friends or by driving around in a car, singing songs together or humming tunes that worked like sonic magic to calm everyone down. This period generated songs and instrumentals that appeared on his first three albums, later collated into 2020’s To Cy & Lee: Instrumentals Vol. 1 — itself quickly championed and sampled by Bon Iver.

His artist name arrived in a suitably idiosyncratic style: He’d been walking down the street, dressed in expressive style, when some men drove past at speed. One of them leant out of the window, shouting. Their actual words were lost to the wind but an approximation arrived in his ears fully formed: Alabaster DePlume.

As well as a new name, he’d gathered strong ideas about recording sessions and live situations. So when life threw some extremely painful storms in his direction he made the decision to record some songs to tape in the one-time ballroom at Lymefield Studio in Middleton. “I had to do something with these feelings and not just collapse and complain. I chose to be ruthlessly glad and to do something enormously perverse — to make this record and to press it to vinyl.” The resulting record was Copernicus — The Good Book Of No, self-released in 2012 in collaboration with a local collective of friends (aka Debt Records). One album led to another and next came The Jester (2013), a collaboration with Daniel Inzani which contained an intention to bring the cities of Manchester and Bristol closer together through the medium of musical relationships. In 2015 he made Peach, recorded inside Manchester’s heavily influential Antwerp Mansions after a dinner in which one of the musician-chef crew cooked up food for 60 people — dinner designed to nourish the music as much as the people who’d play or listen.

Soon after, he moved to London. He ran a launch night for Peach at his new home, the soon-to-be legendary Total Refreshment Centre and this led to a monthly night under the same name. He would invite musicians to play, and as he’d later do with the Gold recordings, would not give them enough time to rehearse. This positive manipulation, along with a community-literate audience ensured that the music contained maximum vibe. The vibe was evident every time he stood up to recite his shamanic and politicised anthems like I Was Gonna Fight Fascism or Buy It and it was evident when the music slowed down time, and drew everyone listening deep into the heart of the sound and the intention. Videos of the event flew far and wide, creating a community of people who’d come to gigs in Moscow, Berlin, or across the U.K. because they’d seen Peach online. “My life and career was transformed by the community of the Total Refreshment Centre,” he says. “It was here that I began consciously using music-making as a tool for generating community and pursuing spiritual emotional growth.”

The situation — which he describes as being ‘made of good will and good faith’ — led to another release titled The Corner of a Sphere (2018). It was an uplifting collection of songs looking at humanity at its best and worst, summed up in the song They Put The Stars Far Away. Since then, DePlume has collaborated with Dan ‘Danalogue’ Levers of The Comet Is Coming on I Was Not Sleeping; activated dozens of campaigners for the Labour Party during the general election; made a new band under the name Calabashed with Joshua Idehen; played a sold-out show at the brilliant Church of Sound in East London at which he recited from memory the final speech of former Chilean president Salvador Allende; released available-for-24-hours-only singles on Bandcamp; and turned his monthly Realistic Behaviour show on Worldwide FM into a celebration of creativity and spontaneity where friends and studio passersby gather to make sound together.

It’s the culmination of the music, the relationships, and the powerfully skewed perspective he brings to life. And there is more to come.”