These albums came out two decades ago. Here’s what I had to say about them back then (with some minor editing):

Rockumentaries are a dime a dozen. From Woodstock to The Filth and the Fury, it seems like every band, every genre, every era and every trend in rock has been preserved for posterity. Jazz documentaries, conversely, are as hard to find as original Charlie Parker 78s. And no wonder. Who’s going to wade through all that old footage, all those pictures, all that music? You’d have to be crazy. You’d have to be obsessed.

Or you’d have to be Ken Burns. The filmmaker who turned the U.S. Civil War and baseball into mammoth, critically acclaimed documentaries has focused on America’s most original — and most overlooked — musical genre. It’s another ambitious work. Ken Burns Jazz is a 10-part, nearly 19-hour series. Six years in the making, it uses dozens of interviews, hundreds of songs, thousands of stills and archival film clips to tell the music‘s story.

Not surprisingly, there’s an equally impressive slate of CDs to go with it. There’s the obligatory box set of music from the series, a smaller single-disc affair and — coolest of all — 22 CDs spotlighting some of the most vital artists in jazz, from Louis Armstrong to Lester Young. I got some of these, and while none really lives up to the claim of “definitive” — no single CD can sum up Duke Ellington’s career — they are thoughtfully constructed primers that provide an overview of an artist’s career at a reasonable price, and will likely whet your appetite for more. Here’s a quick guide to some titles:

Louis Armstrong

Why He Rates: Because the gravel-throated trumpeter and vocalist practically invented jazz as we know it by refining ragtime into swing, pioneering the use of improv and solos, and turning musicians into stars. Basically, when it comes to jazz, Satchmo did it first.

The Standards: The ragtime classic When the Saints Go Marchin’ In, the bouncy Hello, Dolly!, his elegant What a Wonderful World.

Buried Treasure: Early gems like Heebie Jeebies and Potato Head Blues from his Hot Five and Hot Seven combos in the ’20s, when Louis was still defining his signature sound and style.

Sidney Bechet

Why He Rates: Because he’s one of the few artists whose career and fame pre-date even Armstrong; the scrappy soprano saxophone and clarinet player was a star in Europe for decades, but never really got his due in America.

The Standards: His sultry, up-a-lazy-river versions of Summertime and Blue Horizon.

Buried Treasure: Early tracks from when he and Armstrong were both sidemen in Clarence Williams’ band; the swinging reefer blues cut Viper Mad.

Dave Brubeck

Why He Rates: Because the cool-jazz pianist didn’t just break new artistic ground in the ’50s with his ear-catching off-time numbers — he broke new commercial ground by turning them into massive hits.

The Standards: Take Five, one of jazz’s most distinctive tracks; the equally complex 9/8 groove of Blue Rondo a la Turk.

Buried Treasure: The driving, boppy Perdido and I Get a Kick Out of You, which prove Brubeck could get down and swing without all the weird fractions.

Ornette Coleman

Why He Rates: For pioneering one of the music’s most controversial genres — free jazz. In the late ’50s, this squawking alto saxman from Texas discarded the rule book, dispensing with key, harmony and metered tempo in favour of music played straight from the soul. Some said he was crazy; others called it genius. The jury is still out.

The Standards: The dirgey Embraceable You, the only cover Coleman ever recorded.

Buried Treasure: Aptly named tracks like Ramblin’ and First Take, whose boundless creativity and atonal skronk still sound revolutionary four decades after they were recorded.

Miles Davis

Why He Rates: Because he changed the face of jazz as often as his stylish Italian suits. Because he spearheaded cool jazz, hard bop, modal improvisation, and fusion over his four-decade career. Because no one has been able to match his lyrical trumpet style, and plenty have tried. Because he was the coolest cat and baddest mutha around. Because he was Miles Davis.

The Standards: His definitive live version of My Funny Valentine; the elegantly hummable So What.

Buried Treasure: Donna Lee, one of his early sides with sax supernova Charlie Parker; the plaintive Generique, from a rare French soundtrack.

Duke Ellington

Why He Rates: For being jazz’s greatest songwriter and bandleader. The swellegant pianist composed nearly 2,000 songs — many of them now timeless classics — and delivered them in a style that was equal parts suave sophistication and musical substance.

The Standards: Indisputable classics like It Don’t Mean a Thing if it Ain’t Got That Swing; Sophisticated Lady, Take the “A” Train and Satin Doll.

Buried Treasure: Earlier works like East St. Louis Toodle-oo and Black and Tan Fantasy, featuring the inimitable trumpeter Bubber Miley, king of the wah-wah plunger.

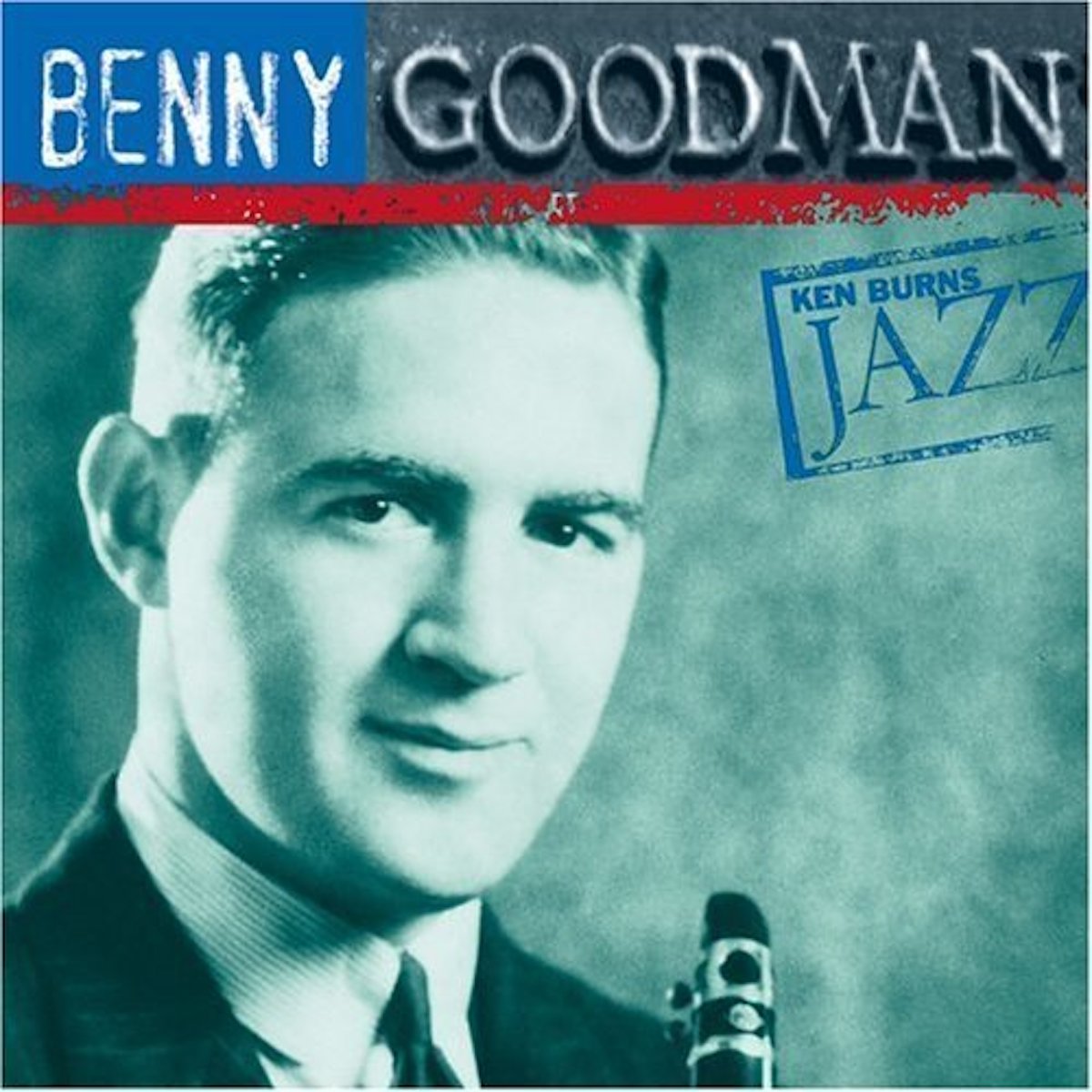

Benny Goodman

Why He Rates: For being the king of big band swing. And we do mean The King — the nerdy clarinetist caused riots with his hot jazz sound and was as big a star in his day as Elvis. His live album from Carnegie Hall is one of jazz’s classic discs.

The Standards: The driving Sing, Sing, Sing, propelled by Gene Krupa’s pounding tom-toms; the simmering horn syncopated of Don’t Be That Way and Let’s Dance; the cool-vibes vibe of Flyin’ Home.

Buried Treasure: The big-band boogie of Roll ’Em; Goodman’s early licorice-stick sides with Red Nichols, Ted Lewis and Jimmy Bracken.

Herbie Hancock

Why He Rates: Because he’s one of the few contemporary artists with a legitimate link to jazz’s glory days — the talented keyboardist played in one of Miles Davis’s finest quintets in the mid-’60s before embarking on an eclectic solo career.

The Standards: The funky Watermelon Man; Cantaloupe Island, which Us3 fans will recognize as the sample that anchor’s the biddy-biddy-bop hit Cantaloop; his electro-pop hit Rockit, which blends jazz with hip-hop scratching and beatboxes.

Buried Treasure: You’ve Got it Bad Girl, a ’95 post-bop workout that brings Hancock’s career full circle.

Fletcher Henderson

Why He Rates: For being the Ronnie Hawkins of jazz. A whole roster of future legends — Louis Armstrong, Coleman Hawkins, Benny Carter, Ben Webster, Roy Eldridge, even Sun Ra — passed through this influential pianist’s band during the ’20s and ’30s, but this unsung hero never quite managed to grab the brass ring himself.

The Standards: King Porter Stomp, which he also arranged for Benny Goodman; the familiar bounce of Happy Feet.

Buried Treasure: Hot and Anxious and Big John’s Special, whose swinging horn lines anticipate Glenn Miller’s In the Mood by several years.

Charles Mingus

Why He Rates: For being not only one of the most distinctive bassists in history, but also one of the most fearless artists in the ’50s and ’60s scene. Influenced in equal measures by Duke Ellington, blues and the church, the L.A.-raised Mingus never shied away from controversy, using his music as a platform to combat racism and infusing his compositions with the same fierce dignity and earthy passion he brought to the bandstand.

The Standards: Goodbye Pork Pie Hat, his haunting elegy to Lester Young; his sadly sweet version of Duke’s Mood Indigo.

Buried Treasure: The kicking gospel-jive of Better Get Hit in Your Soul; the orchestral jazz of his magnum opus The Black Saint and the Sinner Lady.

Thelonious Monk

Why He Rates: For being a true original. The rebellious pianist’s idiosyncratic approach — dissonant chords and circular melodies, delivered in a choppy, almost stumbling style — alienated almost as many as it attracted. But once you’ve heard Monk, there’s no way you’ll ever mistake him for anyone else.

The Standards: Well You Needn’t, Round Midnight and Straight No Chaser, whose familiar, almost nursery-rhyme catchy melodies have been covered by everyone from Miles Davis to high school bands.

Buried Treasure: Solo piano versions of Nice Work if You Can Get It and Midnight that show off Monk’s one-of-a-kind technique and mastery of his craft.