My mother was rightfully suspicious when I asked for a stamp: “What for, son?” I excitedly told her that I was going to double my record collection for $1. I didn’t even need an envelope, I added, holding up the colourful pouch stuffed with my sheet of album selections. Mom became quite steely. “Oh no, you don’t. That’s a ripoff. They’ll send you those records and then you’re on the hook for a whole bunch more at jacked-up prices.”

My mother was rightfully suspicious when I asked for a stamp: “What for, son?” I excitedly told her that I was going to double my record collection for $1. I didn’t even need an envelope, I added, holding up the colourful pouch stuffed with my sheet of album selections. Mom became quite steely. “Oh no, you don’t. That’s a ripoff. They’ll send you those records and then you’re on the hook for a whole bunch more at jacked-up prices.”

Let me say at this point that I was probably 10 years old, maybe younger. So her argument was not convincing at all. I’d still get THIRTEEN records for basically nothing. And I had no other money, so the idea of being financially committed to a contract meant nothing to me. It’s something my parents would likely bail me out of, and I’d get even more records. My mother must have seen these wheels spinning, and snatched the envelope out of my hand. That was that. Not long after, my brothers and my father backed her up that Columbia House was bullshit. Rats.

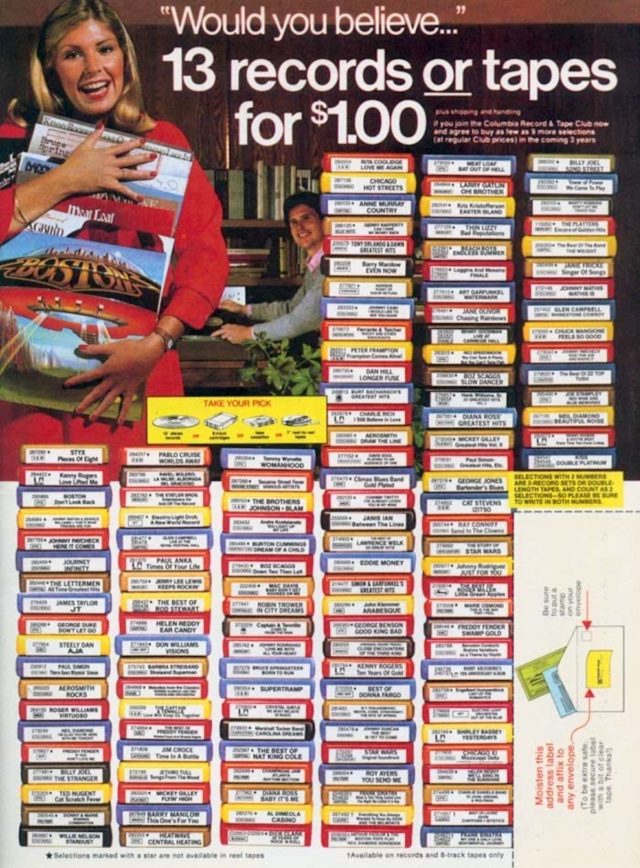

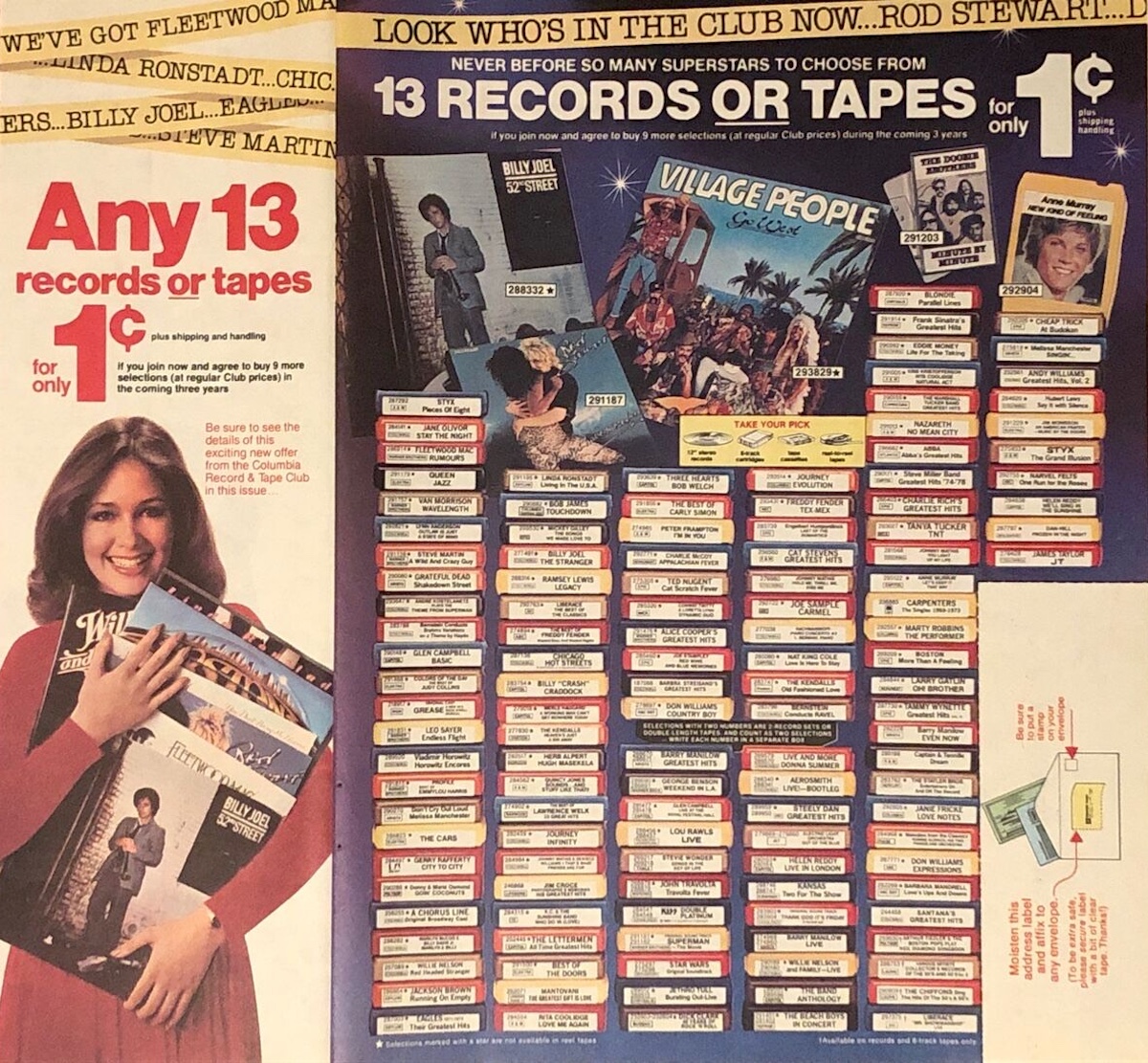

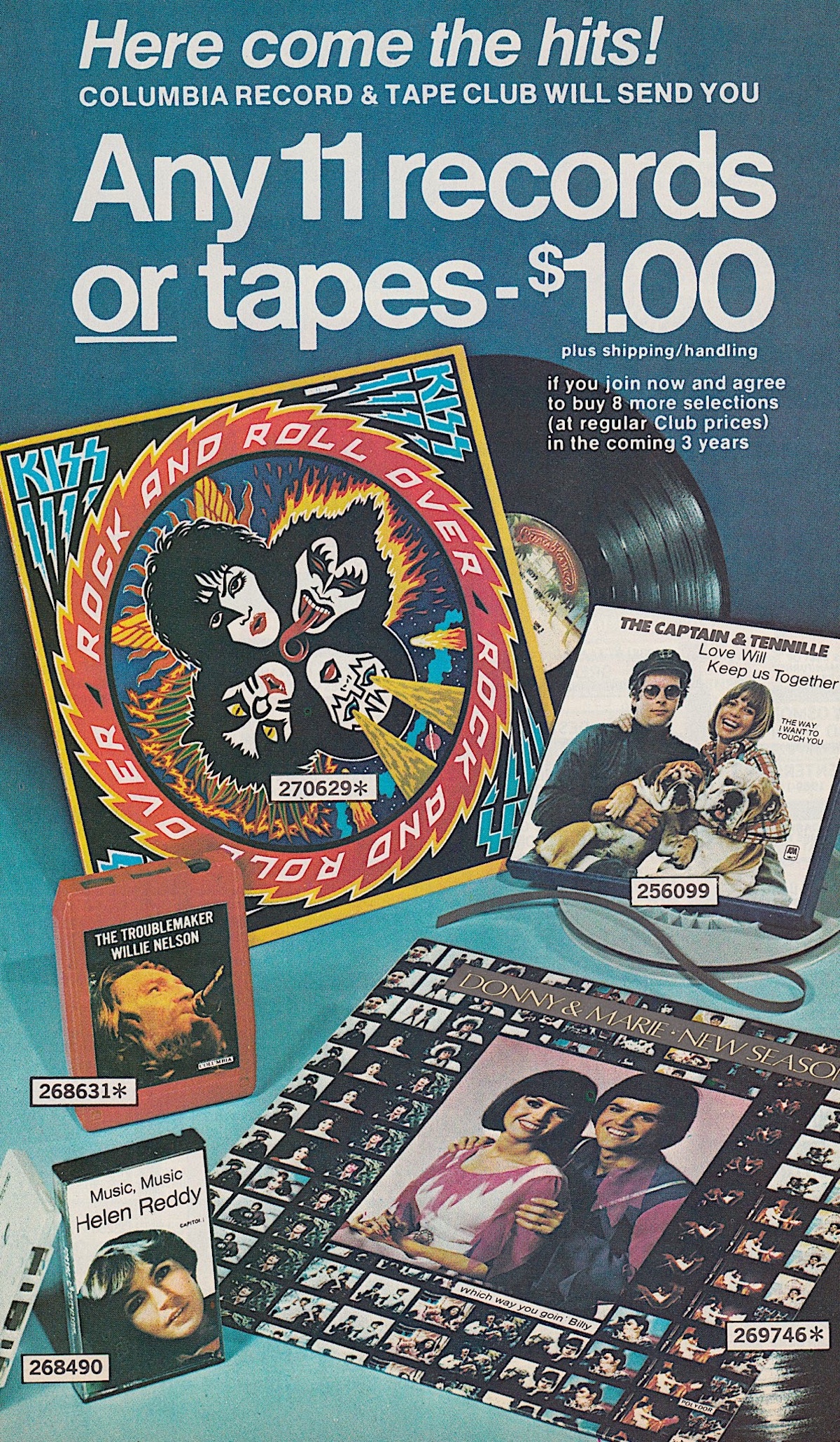

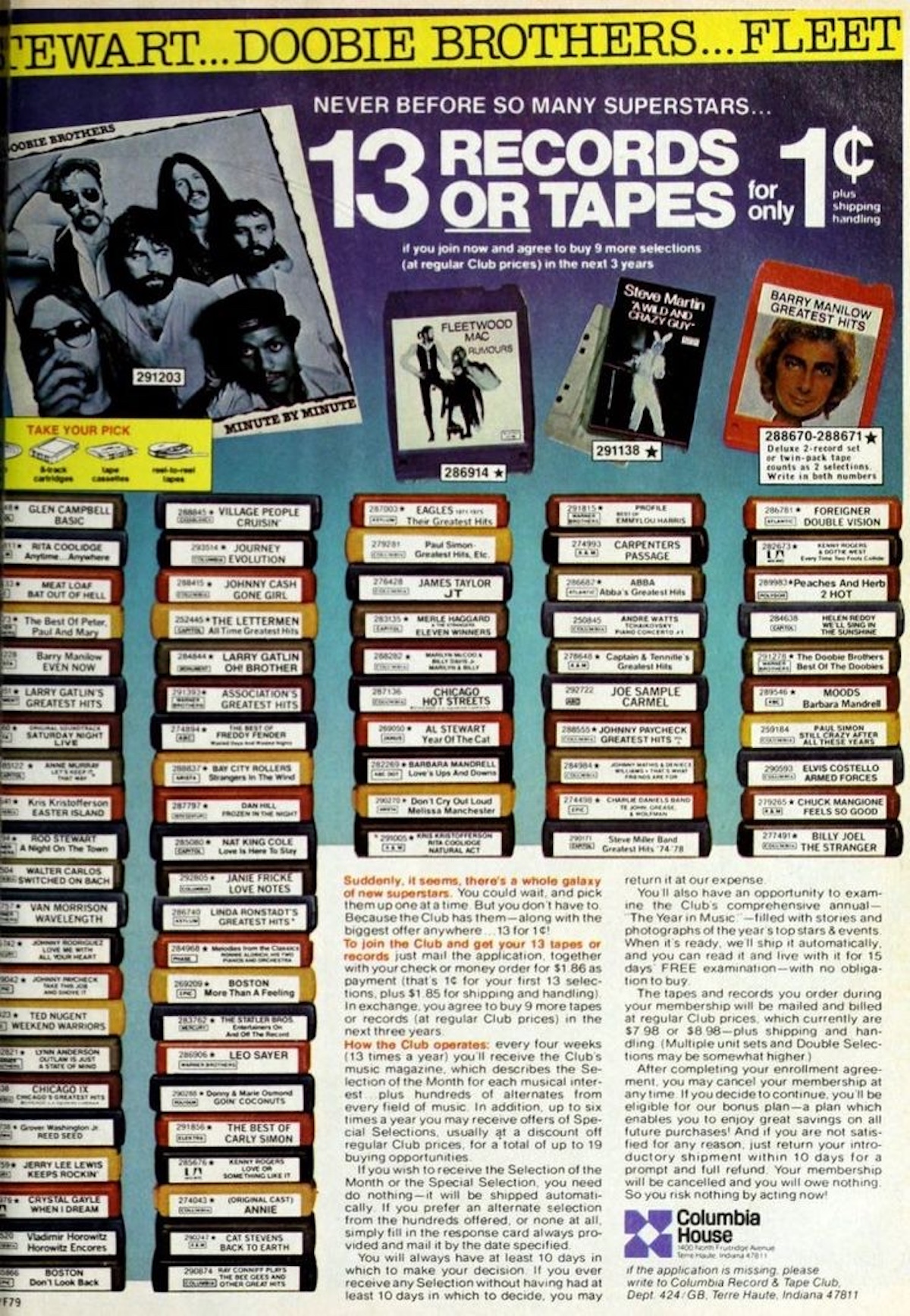

It was so tempting and fun. The record club’s ads/order forms were everywhere in the ’70s and early ’80s — newspapers, magazines and even by direct mail, which I think was the one I got my hands on (serves Mom right for making me walk down to get the mail). I recall reading the thing as I walked back to the house, dropped the rest of the post on the kitchen table, grabbed a pen and took the form to my bedroom to select my introductory records. All I needed the pen for was to write my name and address. The records were selected by peeling off a tiny sticker of the album cover and pasting it onto the form.

I’ve been trying to figure out which ad I saw. I think I found it — the one up top featuring a young woman embracing Boston’s Don’t Look Back, Darkness On The Edge Of Town by Bruce Springsteen, Meat Loaf’s Bat Out Of Hell and a few others. I looked through the albums available and decided to see what I would pick for my 10-year-old self. I went with Aja by Steely Dan, Aerosmith’s Rocks, Supertramp’s debut, A New World Record by ELO, (ironically) Can I Have My Money Back? by Gerry Rafferty, Bad Reputation by Thin Lizzy, Endless Summer by The Beach Boys, The Best of ZZ Top, KISS’s Double Platinum, The Best of The Band, and Out Of The Blue by ELO. Foundational stuff for a kid in 1982. But most of the albums available, in retrospect, were bloody awful, unless you happened to be into Donny and Marie, Donna Fargo or Helen Reddy.

So, was my mom right? Kind of. Columbia House would have definitely come after me to buy more records at full price — plus shipping. But back in the day, there were apparently hordes of people who simply didn’t — and Columbia House usually didn’t do anything about it. Other people supposedly used multiple names to take advantage of the introductory offer, and then just ghosted the company. I could have done that, I suppose. It’s interesting to note that many of those tempted by the offer were kids like me. And because we were minors, Columbia House couldn’t sign us to binding contracts. In other words, I really could have had those albums for nothing, Mom.

Where they seem to have made their money, apart from legitimate market demand, was through the now-common practice of “negative-option billing” — Columbia House would send you records randomly (and charge you) if you failed to make a selection. And if you gave them your credit card information, they would charge you at regular intervals until you managed to cancel. This could be no easy task, as the company didn’t post its phone number on any of its forms or ads. You had to look it up — without the aid of the Internet.

Anyway, it’s worth looking into the story of Columbia House because I have questions. Like, for example, why are these special record-club pressings often worth more to collectors on Discogs than standard pressings? I think it’s because there were fewer of them.

As the name suggests, Columbia House was started by the Columbia record label. It first appeared as the Columbia Record Club in 1955 as a way for people who didn’t live near record stores to get their hands on the popular music of the day. For a few years, the club only sold Columbia records. At the time, this meant artists like Miles Davis, Tony Bennett, Mitch Miller, Mahalia Jackson, Doris Day and Johnny Mathis. But as demand grew, parent company CBS made a deal with other labels so they could expand the mail-order catalog to offer albums on Verve, Mercury, Warner Bros., Kapp, Vanguard, United Artists and Liberty. RCA Victor and Capitol opted to start their own clubs instead. (Elvis Presley and The Beatles were both noticeably absent from my 1982 Columbia House order form).

In those early days, prospective members weren’t offered a dozen records — just a single selection for free. Record stores obviously weren’t fans of this, but were satisfied when Columbia agreed not to make albums available until they’d been on the market for at least six months. If any of those stores convinced customers to join the club, said shopkeep would collect a 20% commission. By the end of 1955, the Columbia Record Club had more than 125,000 members who bought more than 700,000 records. A year later, there were more than 650,000 members who bought seven million records.

The 1960s saw a name change to Columbia House, as well as the offering of stereo records, reel-to-reel tape in 1960, 8-track cartridges in 1966, and cassette tapes in 1969. And here’s another reason why record-club titles can fetch a pretty price on Discogs — Columbia House often had albums that were no longer being pressed by their original label. They also sold formats which were no longer commercially available anywhere else. For example, after the mid-’70s, you couldn’t buy albums on reel-to-reel. But Columbia House continued to make them until 1984. (Check out ReelTapeWorld on Etsy — especially if you want quadraphonic tape.) By 1982, most record companies weren’t releasing 8-tracks, but Columbia House did right up to 1988. You couldn’t easily buy new vinyl after 1989, but members could still get them until 1992. A 1991 record-club edition of Nirvana’s Nevermind can fetch $1,000 — even though Geffen and Sub Pop did a limited vinyl pressing. (There was also a Canadian-specific arm of Columbia House which launched in the late ’50s and went defunct in 1977. It was reborn in 1979 as the Canadian Music Club.)

In the ’90s, the bulk of Columbia House’s sales were compact discs, but the rise of digital music and Amazon started doing irreparable damage by 1999. A planned merger with CDNow was called off because of Columbia House’s financial struggles. And then in 2001, the company had a security breach in which customer information was made public. In 2002, Sony sold 84% of Columbia House to an investment firm, who sold it a year later to BMG Direct Marketing. It was sold again in 2008 to a Phoenix company who finally shuttered its music sales arm, focusing instead on DVDs and Blu-rays. Sony, however, still owns the Columbia House name. The Canadian branch went bankrupt in 2010. The DVD and Blu-ray business went under in 2015.

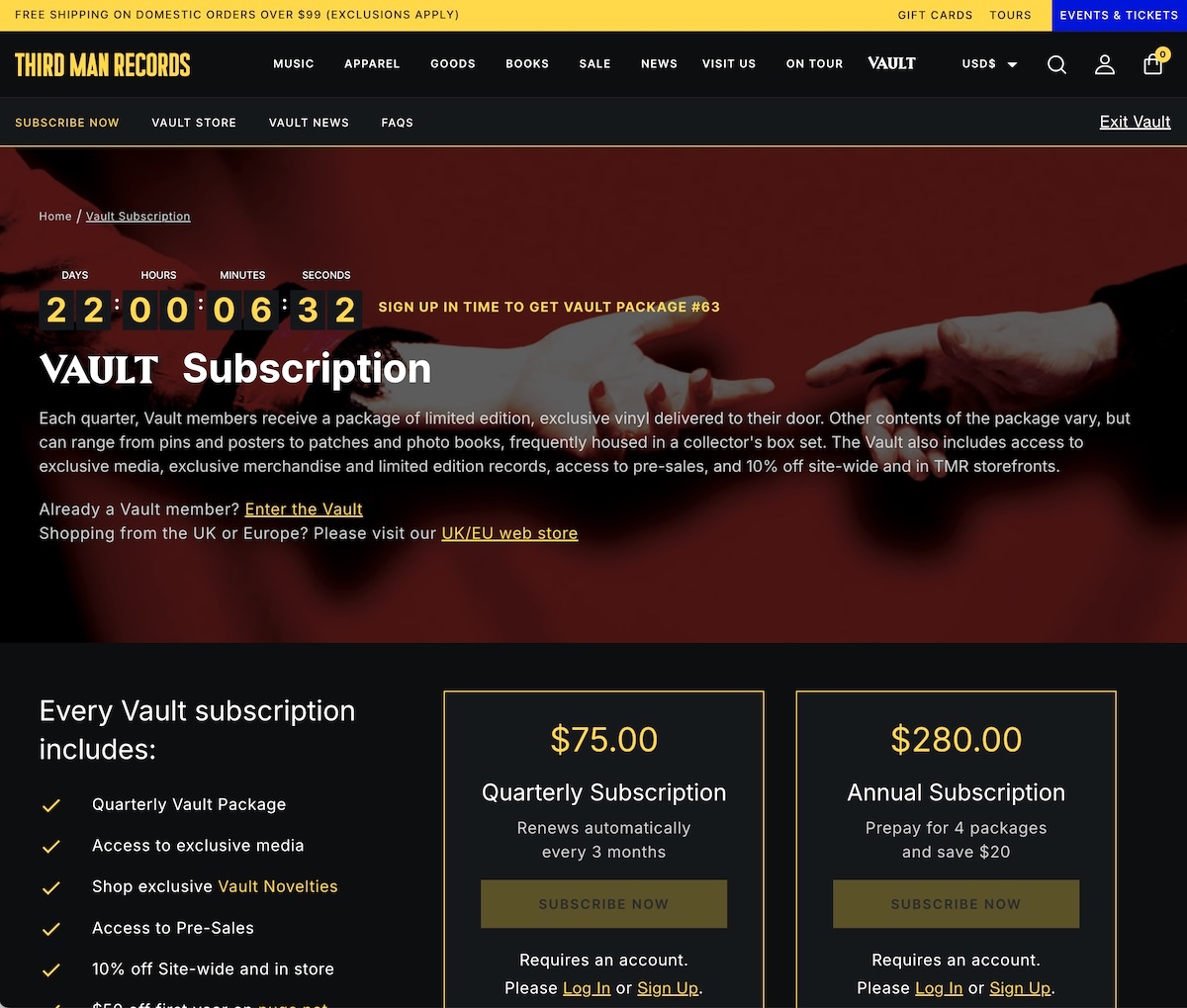

These days, record clubs are mostly the bailiwick of boutique labels like Jack White’s Third Man Records or Canada’s Arts & Crafts. With these, you pay a membership fee and get exclusive offers as well as scheduled delivery of featured packages. Third Man is quite cool. Their Vault gives you access to discounts, exclusive titles and a twice-yearly exclusive pressing or box set. I got a very nice Syd Barrett box with the Pink Floyd founder’s two solo albums and his 1987 outtakes LP Opel. The records are on coloured, 180-gram vinyl and come in a gorgeous box illustrated by Greg Ruth. I also got a deal on some Kelley Stoltz stuff, Monks and, of course, The White Stripes. But I never got to paste any stickers.

• • •

Area Resident is an Ottawa-based journalist, recording artist, music collector and re-seller. Hear (and buy) his music on Bandcamp, email him HERE, follow him on Instagram and check him out on Discogs.