THE EDITED PRESS RELEASE: “Music can be a moment of ignition. Chris Rowley was a 14 year old in late-’70s London, witness to the insurrectionary first wave of punk — his second gig ever was the original Slits — when he learned this spark and promise. When he helped instigate U.K. riot grrrl as a vocalist in Huggy Bear in 1991, he embodied it.

Huggy Bear existed from 1991 to 1994. Inspired by the “seismic shock” of witnessing a Nation of Ulysses performance together, galvanized by Bikini Kill drummer Tobi Vail’s germinal riot grrrl zine Jigsaw, Huggy Bear set out to combine the lessons of both of those groups — “the same slipstream and grit and stardust, otherwise what would be the point?” Rowley recalls — into a highwire “boy-girl revolution.”

For 25 years Rowley never had another serious band. He’s never had a cellphone. Before an interview for this biography — for the new London punk group that broke his long leave from playing music — he’d never used Skype. (Rowley’s 12-year-old daughter encouraged him to try it out.) Rowley had always written off the idea of doing another band, but something changed in 2019 when his comrade John Arthur Webb — formerly of blistering noise-pop trio Male Bonding — asked if he wanted to play music together. When they got in a room, “suddenly it felt super exciting,” Rowley recalls, “and any instincts I might have had to say, ‘Why would I want to do that at this point?’ stopped because it was so much fun.”

Rowley and Webb met in the early 2000s at the Rough Trade shop in Covent Garden. Rowley was a regular customer, buying records from Webb for years, before he ever mentioned Huggy Bear. (After Webb recommended a Skinned Teen/Raul reissue, Rowley “explained he was friends with these bands,” Webb recalled, “because he used to be in a band called Huggy Bear.”) Webb, a huge fan, was shocked, and despite living not far apart, they became penpals.

It was years later at Rough Trade East that Webb and Rowley befriended a then-teenage drummer, Sonny, now 23, who worked there. One day, a mysterious package arrived for Sonny at the shop: “A jiffy bag scribbled all over with phrases and little drawings” that turned out to be “the most illegibly and brain-scatteringly impassioned letter from Chris with a long enough list of record and film recommendations to last me a year.” The phrases on the outside were an extension of the list. Afterwards, Sonny finally decided to check out Huggy Bear and found their legendarily anarchic 1993 appearance on television program The Word on YouTube: “Holy shit.” He offered to drum in Adulkt Life.

After a debut gig, the Adulkt Life lineup was finalized when Webb enlisted his best friend and longtime collaborator, Kevin Hendrick — who has in recent years turned towards solo industrial noise poetry as Middex — on bass. Theirs is a musical partnership spanning nearly two decades: “The whole time, John had this penpal relationship with Chris from Huggy Bear and I couldn’t quite get my head around it, as Huggy Bear were hugely important to me when I was young,” Hendrick says, but Rowley “remained a mystery.”

For Rowley, Adulkt Life “felt like it could carry the weight of all the things I would want to culturally load into a band without having to compromise any of it.” That meant these songs — ecstatic buzzsaw guitars, blown-out poetry, the improvisatory energy of torrential art-punk drumming that reveals Sonny’s free-jazz interest — should reflect the conditions of his life as an older person. In 2020, Rowley is a 55-year-old father and longtime employee of a children’s charity. “You have to create a question and interrogate yourself,” he says, and so he poses inexhaustible ones: What is it to parent in a crumbling world? What does it mean to stay political as Earth burns, to keep loving music? How best to communicate the excitement and charge of possibility from “a whole different set of paradigms”? Adulkt Life inquires but offers no easy answers, instead instigating punk’s eternal invitation to see: “Wow, I should do something — make something, start a political party, just do something rather than not do something.”

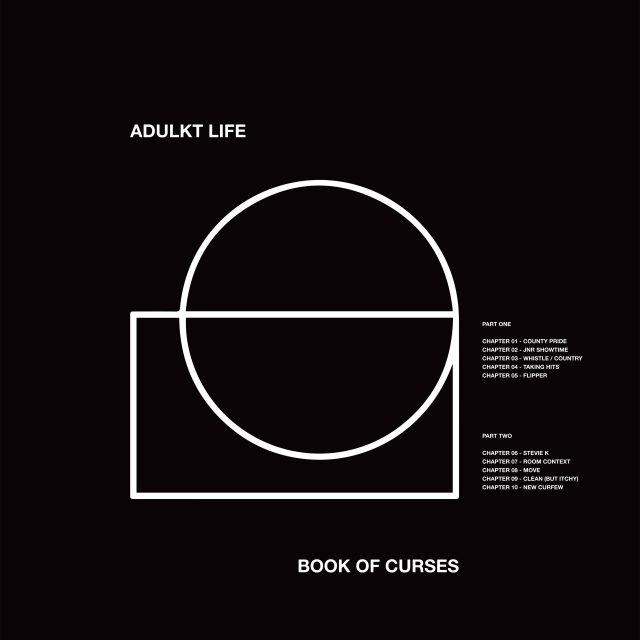

The cut-and-paste word collages Rowley once shouted in Huggy Bear are as cool and thrilling as ever on Book Of Curses — with chiseled noise hooks expertly mixed by Webb and mastered by Total Control’s Mikey Young, fitting the “cold war bubblegum” aesthetic called out in the lyrics — but charged by the high-stakes of adulthood. Taking Hits is a rallying cry for those unable to cry. The brooding Flipper, a “city hymn,” indeed nods to the noise-rock band of the same name. Audibly pained, JNR Showtime addresses child abuse with rage and disgust. Other songs, ablaze, explore lawlessness, authenticity, love, redemption, like fables of radicals across time and space: us versus them, defeat and resurrection, sax squall, noise blasts, visceral empathy for the vulnerable and disenfranchised. Rowley’s apocalyptic visions just happen to appear alongside bedtime stories.

The explosive Stevie K is a “mythic hero/ine song” inspired by Nation of Ulysses guitarist Steve Kroner. “There always has to be a ghost-rider figure you think is ‘out there’ protecting ethics and aesthetics in the face of diminishing returns and a hundred pretenders,” Rowley says. In the 1990s, after Rowley and the other members of Huggy Bear saw Nation of Ulysses, “You couldn’t be a band and want to be anything less than the impact that had on us […] We wanted to shake everybody up.” Adulkt Life honour these impulses.

Even Rowley couldn’t have anticipated the prescience of Book Of Curses’s dynamic, affecting closer, New Curfew, when he wrote it last year — a song about the contradictions of youthful protest and unrest from the perspective of a parent whose daughter may soon be rioting herself. Can he stop her? Would he want to? “I don’t know what I feel when I hear sirens outside anymore,” Rowley shouts. “These kids by the wall under my window/Masks wouldn’t make ‘em more frightening.” It is eerily prescient. But seeing the future starts with paying attention.

Conceptualizing Adulkt Life, Rowley and Webb would joke about what subject matter 40- and 50-something punks might take on. “But they’re not ridiculous ideas,” Rowley says. “We’re not chasing after being young. As you get older, there’s always going to be an obstacle. There’s always going to be an enemy. There’s always going to be that grasp at something transcendent. It doesn’t change when you’re 60 and 70 — it’s the same.”

On Book Of Curses, punk means never surrendering your creativity or your curiosity — Sonny, born in 1997, feels the weight of that, too, as he speaks of “fighting adulthood from the inside out … I’m throwing uppercuts from below, while the others are punching from higher up the ladder of adulthood … prying it open and forcing in a defiant extra element in the shape of a K.” K — as in knowledge? KO’d?

“Hey where’d that K come from?” Sonny adds. “Maybe it was carried over from being a Kid. The id is still there, but less on show, with molten ideas coming out of improvisation before solidifying into something tougher, a two-minute block of smoldering cinder. Or maybe it was just a typo.”