Prog fans know Rick Wakeman has a way with a keyboard line. Turns out he can also handle a punchline.

Like countless others, I learned that watching Wakeman’s hilariously ribald speech when Yes was inducted into the Rock and Roll Hall of Fame in 2017. Sample joke: “I remember (my dad) sat me down once and said, ‘Son, just don’t go to any of those really cheap, dirty, nasty, sleazy strip clubs. Because if you do you’ll see something you shouldn’t. So of course I went — and I saw my dad.”

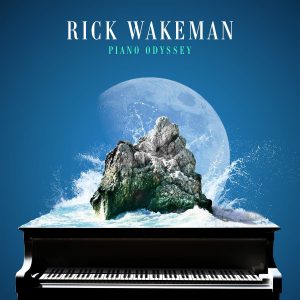

Since then, the 69-year-old Wakeman has enjoyed a far more pleasant surprise: The unexpected success of his 2017 album Piano Portraits, featuring solo piano performances of Yes classics, songs he played on as a session musician and old favourites from the glory days of pop and rock. Inspired by a live radio performance of David Bowie‘s Life on Mars? following the singer’s death, the album hit the Top 10 in his native U.K., spawning the recently released (and more expansive) sequel Piano Odyssey.

It’s just the latest chapter in a decades-long career that has included nearly 100 albums, five stints with Yes, three heart attacks and a production of The Myths and Legends of King Arthur and the Knights of the Round Table On Ice. A few hours after driving home from a solo gig, the flaxen-haired icon called up from the music room of his home in England to chat about comedy, soup, capes and his eternal ice-show dreams. Here’s some of what he had to say:

Did you prepare that Rock and Roll Hall of Fame Induction Speech ahead of time?

No. I do a lot of standup over here in England. I do a show with the piano which is half music and half standup. I’ve been doing that for a number of years and I’m known for doing it over here. So Jon (Anderson), Trevor (Rabin) and I were talking earlier in the day. And we thought, the speeches are so boring. It’s the same with the Oscars and all those things. How many times can you thank the man who delivers your milk and the fellow who cuts the trees down in your garden and your Auntie Mabel and granny who bought you your first guitar string or whatever? The truth of the matter is, everybody who’s there knows the history of the band anyway. Otherwise they wouldn’t be in. And Jon and Trevor said, ‘Go on, go for it. Liven things up a bit.’ So I thought, I haven’t got time to do a routine, so I’ll just pick bits from it. I’ll start with a couple of lines. If it dies, I’ll just say, ‘Thank you very much’ and walk away.’ And if people like it, I’ll do a bit more. That was it, really.

It seemed to go over pretty well.

It was interesting. I had loads and loads of people who said really nice things about it. The New York press thought I was irreverent. But I don’t give a toss. It was just a bit of fun. I was glad to be inducted. I was glad that Yes got inducted. I thought the band deserved it. My sadness was that Chris (Squire) had died and wasn’t there. That would have been great. But that’s happened with other bands. It happened with Jon Lord from Deep Purple, and with Keith Moon and John Entwistle from The Who. So my only thing is I wish they would bring bands in a little earlier. But it was really good fun.

How did you choose the pieces for Piano Portraits? On the first album, it was based on your personal connection.

I’d been asked if I’d do Piano Portraits 2 and I said no. Because I had picked pieces that worked solo on the piano and stood up on their own. And I didn’t want to go back to my short list and just pick the next 12. But there were a lot pieces I wanted to do that I couldn’t do because I felt they needed something else apart from the piano — little splashes of colour. But the basic criteria for me was first of all, it has to be a great melody. It has to be a melody that you could do variations of and play around with. And then the thing was, I didn’t want to just do piano pieces with orchestrations and arrangements over top. I treated everything a bit like (Cat Stevens‘) Morning Has Broken. When you listen to it, you might think the piano plays all the way through. And it doesn’t. The piano just plays between the verses and a couple of little flourishes. That’s all. But the impression is that the piano is there all of the time. And I wanted to do that. So the orchestra is there and the choir. And there might be the impression that they’re there a lot. But they aren’t actually. They’re just there to enhance in places where I felt it needed that splash of colour to add to the piano.

Did you have to learn these songs, or did you already know them all?

Well, I did know of them all. But I’d never played them. Take (Simon & Garfunkel‘s)The Boxer. I liked The Boxer because it’s not the normal verse-chorus, verse-chorus thing. It was a memorable tune. And it was memorable without the words. And Wild Eyed Boy From Freecloud, I played piano on the original with David Bowie. So I knew it, but I had to readapt it. A lot of them I knew, but I had to go back and brush up on them. So I spent a certain amount of time looking at the original music for all of the pieces, dissecting them and finding a way that I felt worked. So there was actually a lot more preparation than you might think.

They’re all vintage pieces. Are there any contemporary songs you would like to cover? Or do they just not write ’em like that anymore?

You’ve hit the nail on the head to some extent. Music and songwriting has changed a lot in recent years. I’m not saying there aren’t melodies; of course there are. But they’re not strong-enough melodies for me to play around with. The majority of The Beatles’ melodies, you can get hold of them and you can do variations and still, it’s recognizable. It’s very hard to do that with contemporary stuff. I do wonder what my grandchildren are going to be singing around the Christmas tree in 50 years.

You’re very much an album artist, but we live in a song-oriented era. Does that change the way you approach what you do?

No, I must admit, I’ve never ever had the end-market in mind. I just did what I felt and what I wanted to do musically. But there’s an interesting thing happening now, as you know. Music moved into downloads and streaming and the CD market slowly seemed to disappear. And suddenly, the younger generation has rediscovered vinyl, and loves all the artwork and the sleeves and the tactile nature of actually seeing something work. And what is pleasing for me is that we haven’t lost any of the new ways of listening to music and buying music. But we’ve brought back some of the ones that were discarded. It’s not the older generation that’s buying it. And they’re buying vinyl as well as the CD as well as downloading it. So you can have a lot of the same music on five or six different formats, using whichever one suits you at the time.

Were you surprised at how well the albums have been received? Do you plan to do more?

I must admit, I have been very pleasantly surprised by how well they’ve done and how much people love them. It’s always lovely when you do something that you enjoy and believe in and then it gives joy to other people as well. That’s always very nice. As for another album, it would have to be something very different, something uncontrived. It would have to be, ‘Hey, I’ve got a great idea of what to do next.’

How about a comedy album?

There’s a thought! That’s a very good thought, actually. I should bear that one in mind.

On to the important questions: How many capes do you own and what happens to the old ones?

I’ve got about 12. I’ve got five of the old originals from the ’70s which I take out every now and then and use. And then I’ve got some newer ones. So the newest is about two years old and the oldest would be … oh gosh, let’s see; it was 1971, so that would be 47 years. I put one into into a big charity auction quite a few years ago. And I was there, and they were holding it up, and I thought, ‘I can’t bear to do this.’ And I couldn’t withdraw it because it was a charity auction, so I ended up buying it back!

Your Twitter feed is very soup-based. What’s the deal?

(Laughs) When I started doing Twitter, a couple of actor friends said just to do the odd tweet a day and have a bit of fun. I do like cooking, I must admit. But it’s really funny — when I do things about soup and go out and do concerts, I’ll literally have a few hundred people come up to me to talk about soup and what they’re making. It’s hilarious.

At this stage, is there anything left on your bucket list? Or do you even think in those terms?

Oh yeah. I’ve got lots of things I want to do. It’s finding the time. In fact — and this is absolutely true — I’ve had written in my will that if there’s a tombstone after I die, what I want written on it is, ‘It’s not fair: I’m not finished yet.’ Because that’s the truth. Jon Lord was a tremendous friend of mine and I did his eulogy at his funeral. And I stood by the coffin and I couldn’t help but think: ‘I wonder what music you’ve taken with you?’ So I’ve got loads of things. I’ve got a ballet that I want to do. I’ve got another concept album that I’m really keen on getting through and that I work on. I want to do another out-and-out prog record. I’m doing a children’s musical at the moment with my wife. There will never be a time where there isn’t something I want to do. So the bucket list turns into a barrel.

How about another ice show?

Funny you should say that. One of my real dreams — and in fact, I spoke to my manager about it only today — is that I want to do King Arthur On Ice again. Because you could do it so differently now than I did it originally. You could make ice sculptures. You can do all sorts of things. That is something that is really high on my list. The cost of putting it on is just phenomenal. But I’m 70 next year, and it’s something I would love to do for my 70th birthday year.

Well, we have ice rinks coast to coast in Canada. We’ve got the venues for you.

That would be absolutely brilliant. I’d be up for that, I assure you!

We’ll pencil you in for next year!

Bless you! Thank you very much!