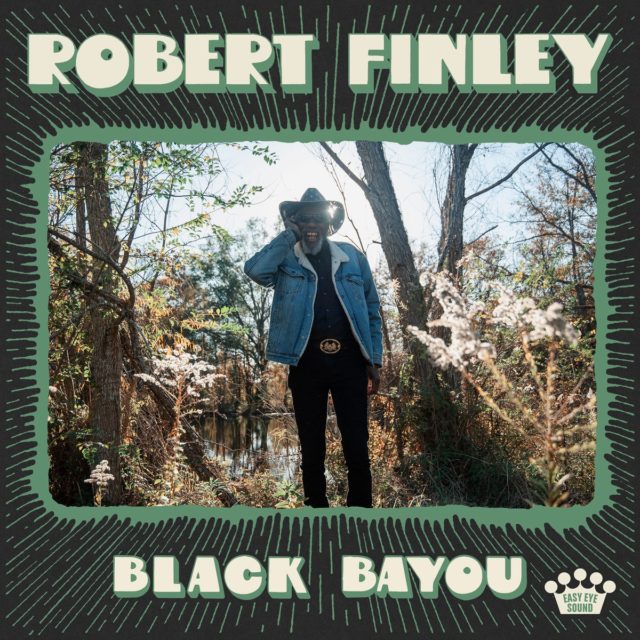

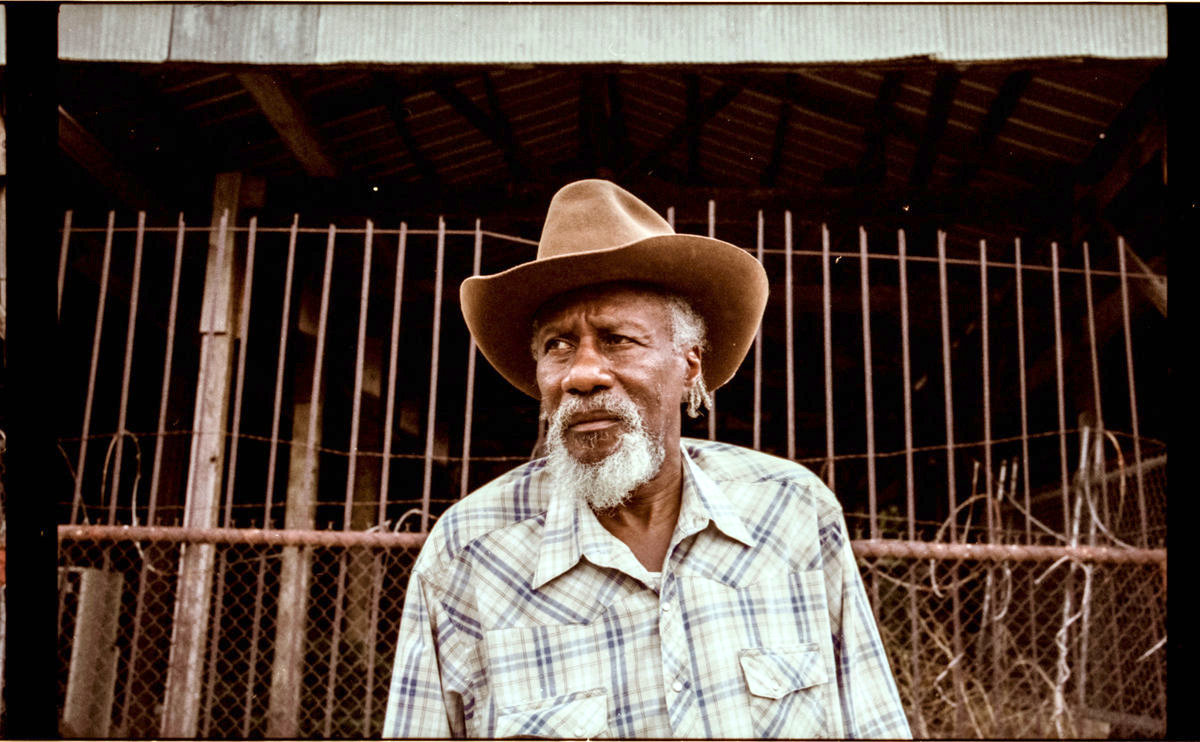

THE EDITED PRESS RELEASE: “I remember the first time my pawpaw took me down to the Black Bayou,” Robert Finley recalls on Alligator Bait, a talking blues that closes out his visceral and vibrant new record. As the guitars pop and crackle around him, coalescing into a slow rhythmic crawl like an airboat along muddy waters, the 70-year-old Louisiana native casts back in his memory for this harrowing story.

Dressed in swamp boots and waders, the kid “stepped on a log and the log moved!” His grandfather shot the gator that snapped at him, but the boy quickly realized that he was intended as bait. There’s some humour to the outrageous incident, but the song emphasizes the tragedy of it: How he was never able to forgive his grandfather for risking his young life, how the incident drove a wedge through several generations of Finleys.

“A song should tell a good story,” says Finley 60 years later. “By the time you hear it beginning to end, it should be like reading a short story or a novel. It should be more than just a laugh. It should leave some kind of impression on whoever’s listening to it. And it should stay as close to the truth as possible.” He’s a masterful storyteller, and Alligator Bait, like the rest of Black Bayou, has the richness of detail, the depth of character, the tragedy of betrayal, the promise of forgiveness — in short, the immense complexity of emotion and humanity — that defines great southern literature.

Finley recorded that song and the rest of the album up at producer Dan Auerbach’s Easy Eye Sound Studio in Nashville. It’s the fourth time the duo have worked together, although for this record they did things a little differently. Rather than write songs beforehand, they devised everything in the studio, with Auerbach leading a band of some of the finest players around: drummers Patrick Carney (aka Auerbach’s Black Keys bandmate) and Jeffrey Clemens, bassist Eric Deaton, guitarist Kenny Brown and vocalists Christy Johnson and LaQuindrelyn McMahon — the latter two just happen to be Finley’s daughter and granddaughter. They worked quickly, devising their parts spontaneously and usually getting everything in one take. “I started singing, and they started playing,” Finley explains. “That’s how we made the album. It wasn’t written out. Nobody used a pencil and paper. We just sang and played together in the studio.”

Together, they created a vivid collection of songs that depict life in North Louisiana, with Finley playing the role of charismatic and knowledgeable tour guide through these swamps and forests. He was born in Winnsboro, but has spent most of his life in Bernice, a small town of about 1,600 souls just thirty miles from the Arkansas border. For years he worked as a carpenter while playing blues in juke joints and singing gospel in churches around the region. Mixing in southern soul, heavy rock, swamp pop, jazz, folk, and anything else that crosses his mind, Finley developed and refined an exuberant and omnivorous playing style. At age 60, however, he lost his sight due to a medical condition — a tragedy that ended his woodworking business but gave him more time to devote to music.

Over the last seven years, he has released three critically acclaimed albums — including 2021’s autobiographical Sharecropper’s Son — and even appeared on the 14th season of America’s Got Talent, making it to the semi-finals. In addition to touring as a headlining act, he has shared bills with The Black Keys and the Easy Eye Sound Revue, and even opened for Greta Van Fleet, which established him as an energetic and uniquely charismatic performer bringing his larger-than-life personality to the stage. All of those experiences come to bear on Black Bayou, especially on songs like the lusty Sneakin’ Around and the devastating Gospel Blues. “I decided to put as much of the Louisiana lifestyle as I could on this album,” he says. “I was raised here, and I wanted to do something good for this place. I wanted to show what life’s like around here. A lot of people in the city, they’ve never been to a swamp or seen a live gator. They’ve never eaten gator meat. They don’t know anything about this place, so I want to show them.”

Adds Auerbach: “It’s amazing to realize how much of an impact Louisiana has had on the world’s music, and Robert embodies all of that. He can play a blues song. He can play early rock ’n’ roll. He can play gospel. He can do anything, and a lot of that has to do with where he’s from.”

North Louisiana is a place where struggle and celebration commingle in everyday life, where death looms, through the jaws of an alligator or just the gradual pace of time. Finley opens Nobody Wants To Be Lonely with a line about visiting a friend at a nursing home — not the typical subject matter for a blues song, yet not dissimilar from the isolation and despair often associated with the genre. “So many people have been forgotten,” Finley explains. “Their kids drop them off and go with their lives. I go down occasionally and perform at the old folks home in Bernice. Just take my guitar and play for 30 minutes or so, try to get them to dance, try to bring some joy to them.”

Black Bayou captures these small moments of life, the tragedies and betrayals, the triumph of making it another day. Despite the success of his previous albums and the demands of touring the wide world beyond Bernice, Finley isn’t keen to call any other place home. “Livin’ in the city’s just a waste of time,” he laughs on Waste Of Time, with its heavy riffs and gravel-road groove. “I’m not interested in living in no big city,” he says. “There’s good places here for hunting and fishing. I can fall asleep in my yard or sleep out on my porch, and nobody’s gonna bother me. Nothing bad is gonna come and get me.”

Finley still plays small clubs around the region — even the occasional nursing home — with a small crew of local musicians that includes his daughter and grandchildren. Rather than move to where the music industry is, Finley is bringing the industry down to Bernice and working to boost regional acts. Whether he’s building a new studio on his property or sharing stages with up-and-comers, his goal is to do for them what others have done for him: Get their music out to the wider world, find bigger audiences, amplify their voices. “We got a lot of good talent down here in North Louisiana, but nobody’s really done much with it. A lot of people just haven’t had the opportunity to record — or even just be heard. It worked for me, so I might as well try to help someone else get discovered, too.”

If previous albums established him as a formidable blues and soul artist, Black Bayou reveals Finley as something even more distinctive: A truly original Louisiana storyteller who evokes the place and its unique culture for the rest of the world. “A lot of people think the blues is supposed to be downbeat and sad, but that’s not all it is. It all depends on the artist and the stories they’re trying to tell. To me, it’s an expression of what people are going through in life, whether they’re here in Bernice or wherever. It’s reality. And reality can be sad, but there are also a lot of happy times, too.”

Or, as he sings on the album’s opener, Livin’ Out A Suitcase: “Been around the world, seen some of everything, but what I like about it the most is the joy that I bring.”