I am currently waiting for test pressings to arrive of my eighth album — the fourth one for which I’ve opted to make vinyl copies. It ain’t cheap — roughly $20 per unit — but that price slides a little if you get more than 100 of them. Basically, 100 records is around $2,500 and 300 was around $3,000 when I got that many of my second album back in 2017. More to my eventual point, these are not fancy album packages: The new album is on white vinyl, is shrink-wrapped with a barcode but has no insert. The 2017 album, Delano, was on black wax with shrink, a barcode and a single-sheet paper insert.

I am currently waiting for test pressings to arrive of my eighth album — the fourth one for which I’ve opted to make vinyl copies. It ain’t cheap — roughly $20 per unit — but that price slides a little if you get more than 100 of them. Basically, 100 records is around $2,500 and 300 was around $3,000 when I got that many of my second album back in 2017. More to my eventual point, these are not fancy album packages: The new album is on white vinyl, is shrink-wrapped with a barcode but has no insert. The 2017 album, Delano, was on black wax with shrink, a barcode and a single-sheet paper insert.

Imagine if I tried to do a package like Dark Side Of The Moon — with two posters, artwork which required travel to Egypt, two stickers and a gatefold sleeve. Sure, that’s a classic-era, vinyl-is-king example, but even newer albums like the ones by Dope Lemon — which include things like zoetrope vinyl, scratch cards, gatefolds and posters — would be wildly out of reach for me.

Synchronicity by The Police has more than 30 different cover variants and audiophile vinyl. Styx’s Paradise Theatre, True Colours by Split Enz and the Superman II soundtrack all had laser-etched vinyl. Led Zeppelin’s In Through The Out Door had a water-activated colour-changing inner sleeve and a paper bag hiding which of the five cover variants you were getting until after purchase. Brian Jonestown Massacre’s new album comes with a box of crayons to go with the colouring book-style line drawing cover artwork of a missile launcher. Fancypants.

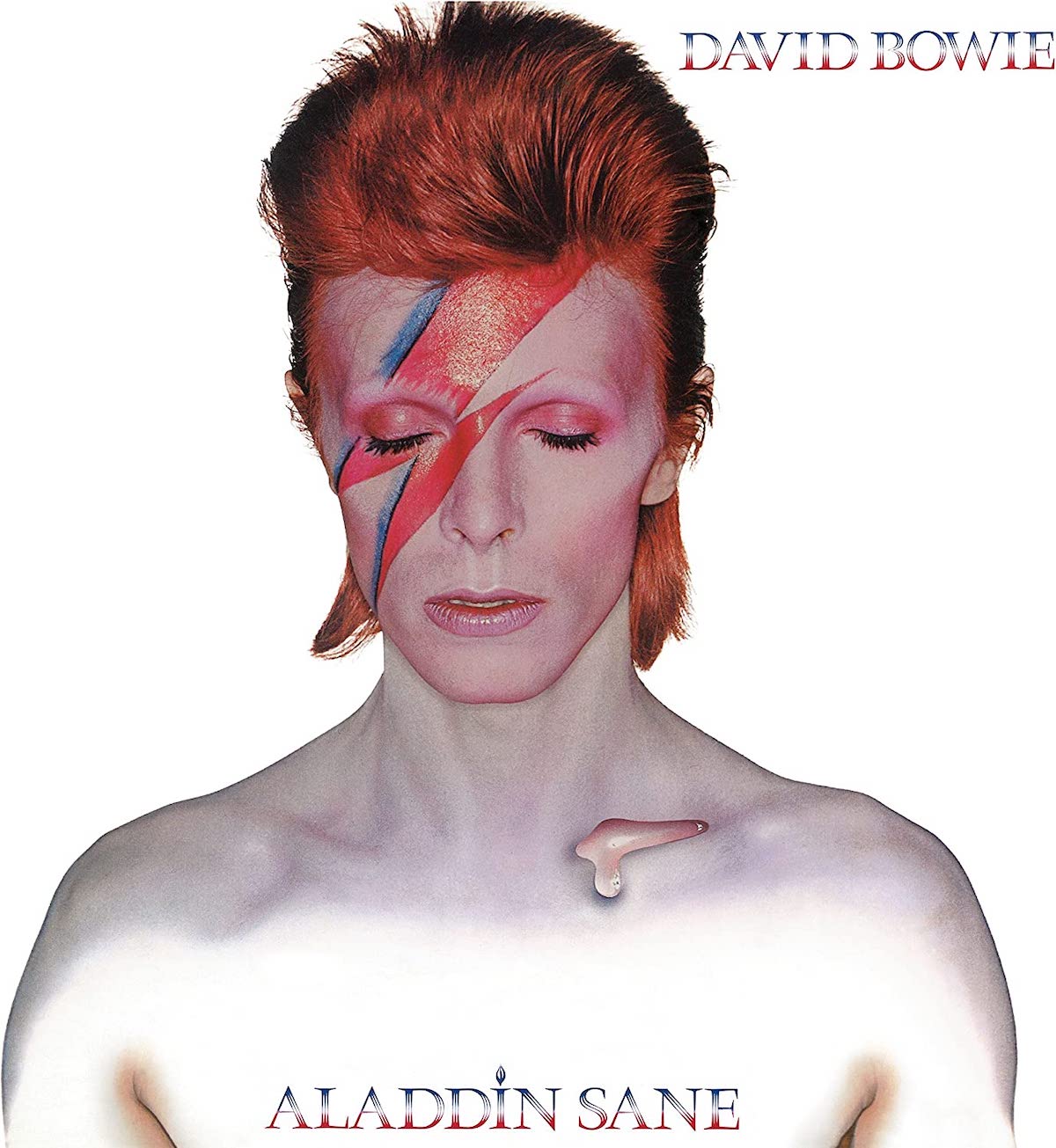

I decided to go looking for the most expensive albums of all time — not to buy, but to produce. Specifically the packaging, not the recording. A classic example is David Bowie’s 1973 follow-up to Ziggy Stardust, Aladdin Sane. It just seems like a normal 1970s glam album, but it is the iconic cover photograph which made it — at the time — the most expensive record ever produced.

The image of Bowie with the lightning bolt across his face was taken by Brian Duffy. Incidentally, the idea for the makeup came from the logo of a National Panasonic rice cooker in Duffy’s portrait studio. Where it gets expensive is with the extensive airbrushing and dye transfer process. The industry standard at the time was four-colour transfers, but Aladdin Sane was printed with an unprecedented seven-colour system. Bowie’s manager was keen to make the packaging as expensive as possible — the logic was this would force RCA to more aggressively promote the album. It worked. Between the popularity of the pre-release single The Jean Genie and the label’s promotion campaign, 100,000 pre-orders of the album helped it debut at No. 1.

The image of Bowie with the lightning bolt across his face was taken by Brian Duffy. Incidentally, the idea for the makeup came from the logo of a National Panasonic rice cooker in Duffy’s portrait studio. Where it gets expensive is with the extensive airbrushing and dye transfer process. The industry standard at the time was four-colour transfers, but Aladdin Sane was printed with an unprecedented seven-colour system. Bowie’s manager was keen to make the packaging as expensive as possible — the logic was this would force RCA to more aggressively promote the album. It worked. Between the popularity of the pre-release single The Jean Genie and the label’s promotion campaign, 100,000 pre-orders of the album helped it debut at No. 1.

Immediate Records only did one 1968 pressing of the original version of The Small Faces’ album Ogdens Nut Gone Flake. The elaborate album packaging won awards, but was far too expensive to turn a profit. It was first issued in a round, replica tobacco tin and contained a poster. Subsequent pressings were on typical album cardboard stock — with a gatefold sleeve.

Alice Cooper’s big 1972 album School’s Out was also originally issued in an expensive-to-produce package. The album sleeve was designed by Craig Braun and die-cut so it could be folded into a school desk — complete with a fold-up lid and the record wrapped inside paper replica women’s underwear instead of a proper paper inner-sleeve.The panties were discontinued not so much because they were expensive, but because they were flammable.

The Beatles’ masterpiece Sgt. Pepper’s Lonely Hearts Club Band was crazy expensive to make — in excess of $800,000 in today’s funds. Much of that was the studio time required and the mountain of classical musicians. But the packaging and artwork were also groundbreaking and elaborate. First, it was one of the first gatefold sleeves in pop music — so it took twice as much cardboard just to do the sleeve. It also was more colourful than other albums — a bright red back cover with black-printed lyrics. It had a patterned inner sleeve and a cardboard insert of cut-outs. By the second U.K. pressing, to save costs, the colourful inner sleeve was replaced with a plain white one, but the cut-outs remained. In the U.S. and Canada, however, the cut-out insert was discontinued after a few years and only came back with anniversary reissues.

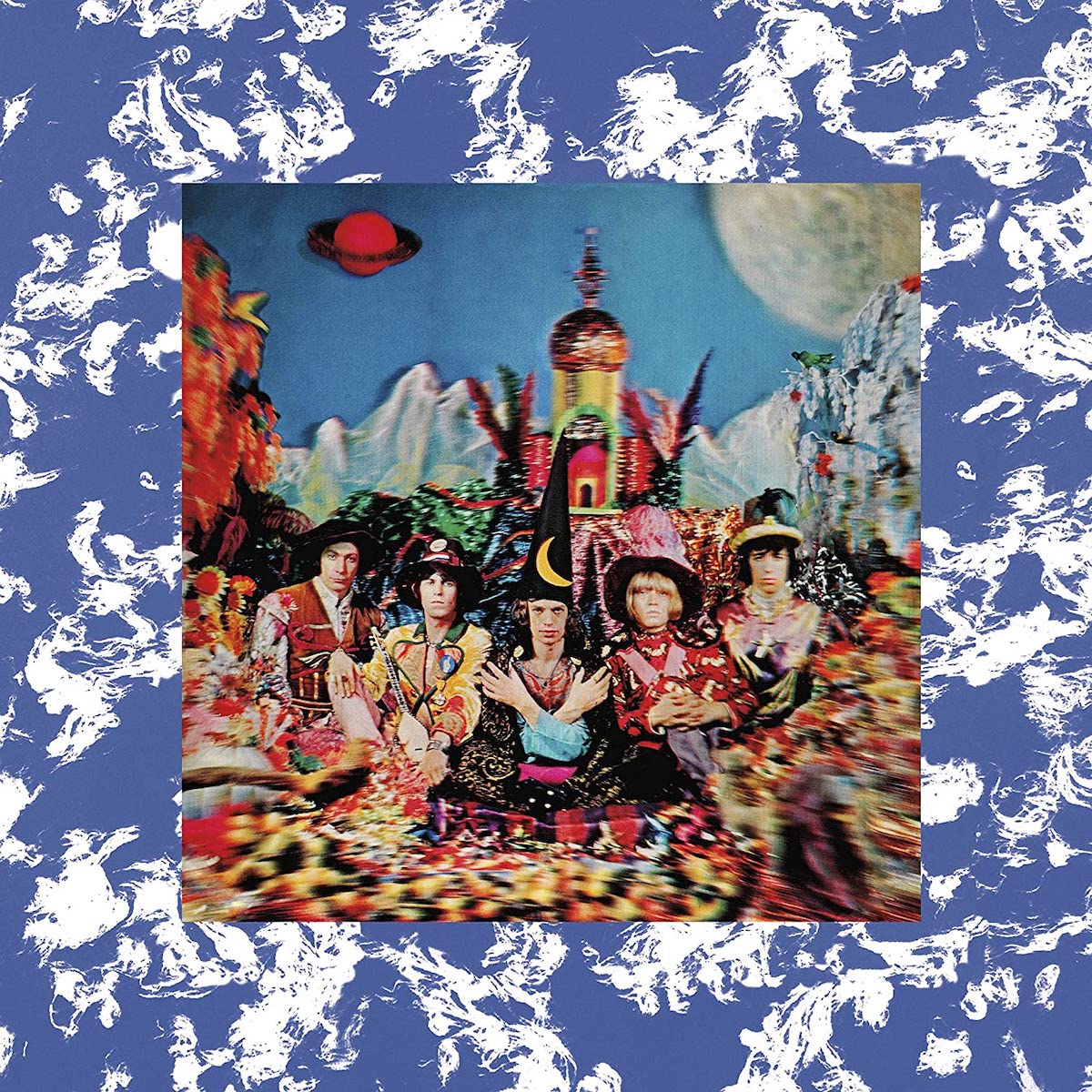

Not long after Sgt. Pepper, The Rolling Stones used the same photographer — Michael Cooper — when they made Their Satanic Majesty’s Request (aka The Stones Are Rolling in some Devil-fearing countries). Cooper is the one who had the idea to do a 3D photo as a way of improving upon the Pepper image. There were only one or two 3D cameras in the world at the time, so they had to do the shoot in New York in order to access the device.

The album took ages to record because of drug busts, the producer quitting and the band members turning sessions into lively social occasions with many guests. That drove up costs — but the production costs most certainly did as well. The gatefold sleeve was fitted with a lenticular 3D photograph of the band on the cover. This is one of those images where it appears those photographed are moving, if you look at it at different angles. In this case, the Stones go from looking straight ahead to looking at each other. All except Mick Jagger, who instead moves his hands.

Stones manager Allen Klein was not terribly supportive of the idea — he made the band build the magic castle, glittery sequined mountains and dangling red Saturn set for the photo themselves. Wood, saws, glitter, glue and Styrofoam. They also had to source all their own clothing. Klein then limited the initial run of 3D covers to 500 copies to cut costs. The lenticular photo — initially intended to take up the entire cover — was made smaller to save money, and then scrapped entirely for a regular band photo on later pressings. There wasn’t another 3D cover until a special limited-edition reprint in the ’80s. As soon as the record was out, they deliberately destroyed the template so no more costly ones could be made. Elaborate and expensive, yes, but it was at least more tasteful than what they originally wanted: To call it Cosmic Christmas and feature a cover photo of a naked Jagger on the cross. Whew. Anyway, the title isn’t really about the devil. It’s meant as a silly version of the phrase you found inside of British passports — “Her Britannic Majesty’s Secretary Of State requests…”

Making lavish album packaging and big budgets wasn’t just a ’70s thing — it was also rampant in the ’90s. Spiritualized’s label Dedicated must have spent hundreds of thousands of pounds on the Warwickshire space-rock band’s third release. Ladies And Gentlemen We Are Floating In Space spared no expense on the recording — which includes choirs and orchestration. But the one variant of limited edition packaging was bonkers — a cardboard box which appears like medication. Inside the box are 12 mini CDs in a blister pack and an instruction sheet on dosage, side effects etc. The discs each contained one song, and were designed to look like two sheets of six pills. Only 200 copies were made, but you could also get it in a one-CD blister pack.

Ah, the ’90s. My pal Jordon Zadorozny told me some interesting stuff when I asked about the cost of getting Storm Thorgerson to do the cover of his third Blinker The Star album, August Everywhere in 1998. Thorgerson, of course, was one of the key individuals who made up Hipgnosis — the art group who did album covers including Dark Side Of The Moon, Houses Of The Holy, Wish You Were Here and Dirty Deeds Done Dirt Cheap. Zadorozny said his label shelled out $40K U.S., around $20K of which was Thorgerson’s fee. “The shoot was mega-expensive because of the freezer truck that had to be kept cold in the hottest climate on Earth,” he says, referring to the “star” of the album cover — a large ice swan, photographed in Death Valley.

The swan — made by a world-class sculptor from Venice Beach who was also a childhood friend of Brian Wilson — was one of four, which could easily break at the neck and had to be handled carefully. The freezer truck broke down on the way to the shoot. So it was a bit hectic, but Thorgerson still saw the art in all of it. “The ice swan was always going to die,” he said at the time. “Inexorably, inevitably, sadly melting away in the desert heat. A phoenix in reverse, turning into water in order to replenish the parched earth beneath: a noble but pathetic gesture, for it was only a drop in an ocean of dryness.”

• • •

Area Resident is an Ottawa-based journalist, recording artist, music collector and re-seller. Hear (and buy) his music on Bandcamp, email him HERE, follow him on Instagram and check him out on Discogs.