THE EDITED PRESS RELEASE: “The story of White Jesus Black Problems begins roughly 270 years ago, when a white indentured servant from Scotland named Elizabeth Gallimore fell in love with an enslaved Black man whose name, like so much else, had been stripped away from him by his captors.

The pair lived in the colony of Virginia, where interracial relationships were not only taboo, but legally forbidden, and their romance put their very lives in danger. The same laws that prevented the two from ever marrying, however, also affixed their offspring’s legal status to that of their mother, meaning that after seven years of their own indentured servitude, Gallimore’s children would be granted their freedom, as well. And so the unlikely couple begot a generation of free African-American children, who in turn begot another generation of free African-American children, who in turn begot another generation of free African-American children, on and on down the line until the birth of their great-great-great-great-great-great-great-grandson, Xavier Amin Dphrepaulezz. Or, as you most likely know him, Fantastic Negrito.

“I remember learning all of this for the first time last year and it felt like the room was spinning,” says Negrito. “I’d never heard anything like it. These two risked an incredible amount of pain and suffering all in the name of love. They took on white supremacy in the 1750s, and now I’m here as a result. I had to write about it.”

Negrito did more than just write about it, though, crafting both an extraordinary full-length studio album and an entire companion film set to the music. The resulting multimedia work, White Jesus Black Problems, is part love story and part historical excavation, an extraordinary and exhilarating ode to the power of family and the enduring resilience of our shared humanity. Written, recorded, and filmed in Oakland, California, where Negrito grew up, the collection is bold and thought provoking, grappling with racism, capitalism, and the very meaning of freedom itself, all without ever losing sight of the desire and determination at the heart of the tale.

The performances, meanwhile, are similarly ambitious and emotionally charged, mixing blistering rock ’n’ roll grit with infectious R&B grooves and buoyant funk energy to deliver a sound that manages to feel both vintage and experimental all at once. While each track here could stand easily on its own, stepping back to absorb the work in its full audio and visual context yields a far more transcendent and immersive sensory experience, one that challenges our notions of who we are, where we come from, and, perhaps most importantly, where we’re headed.

“At the end of the day, this is a record about love,” says Negrito. “There’s a feeling out there right now that we can’t get anything done because we’re so polarized, so entrenched in our ideologies and unmoved by facts or logic, but I wanted to share this story because I think it smashes that narrative to pieces. Despite the horrific challenges these two faced, they found a way to be together, and the ripple effects of that act of love have been reverberating for hundreds of years.”

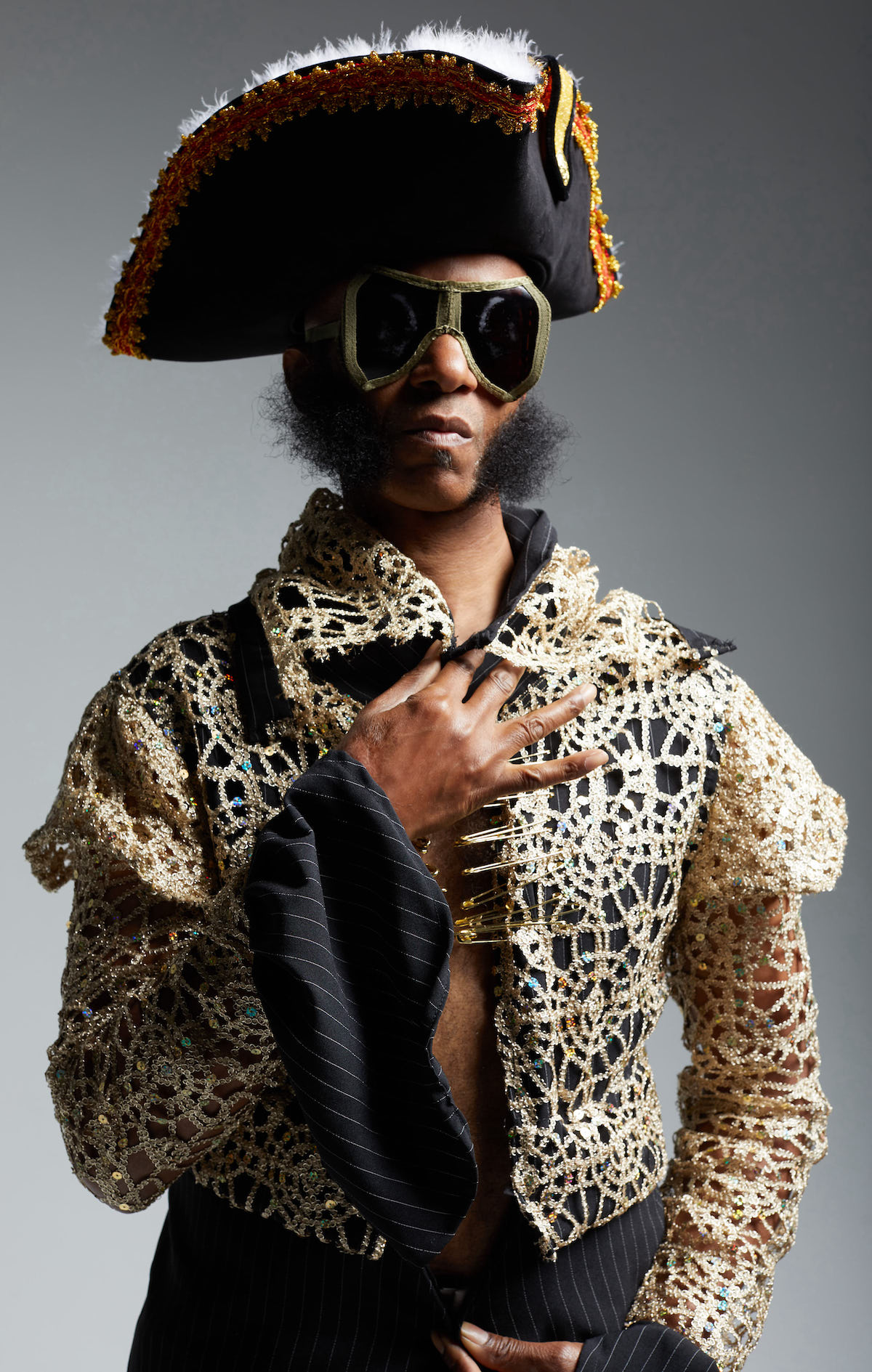

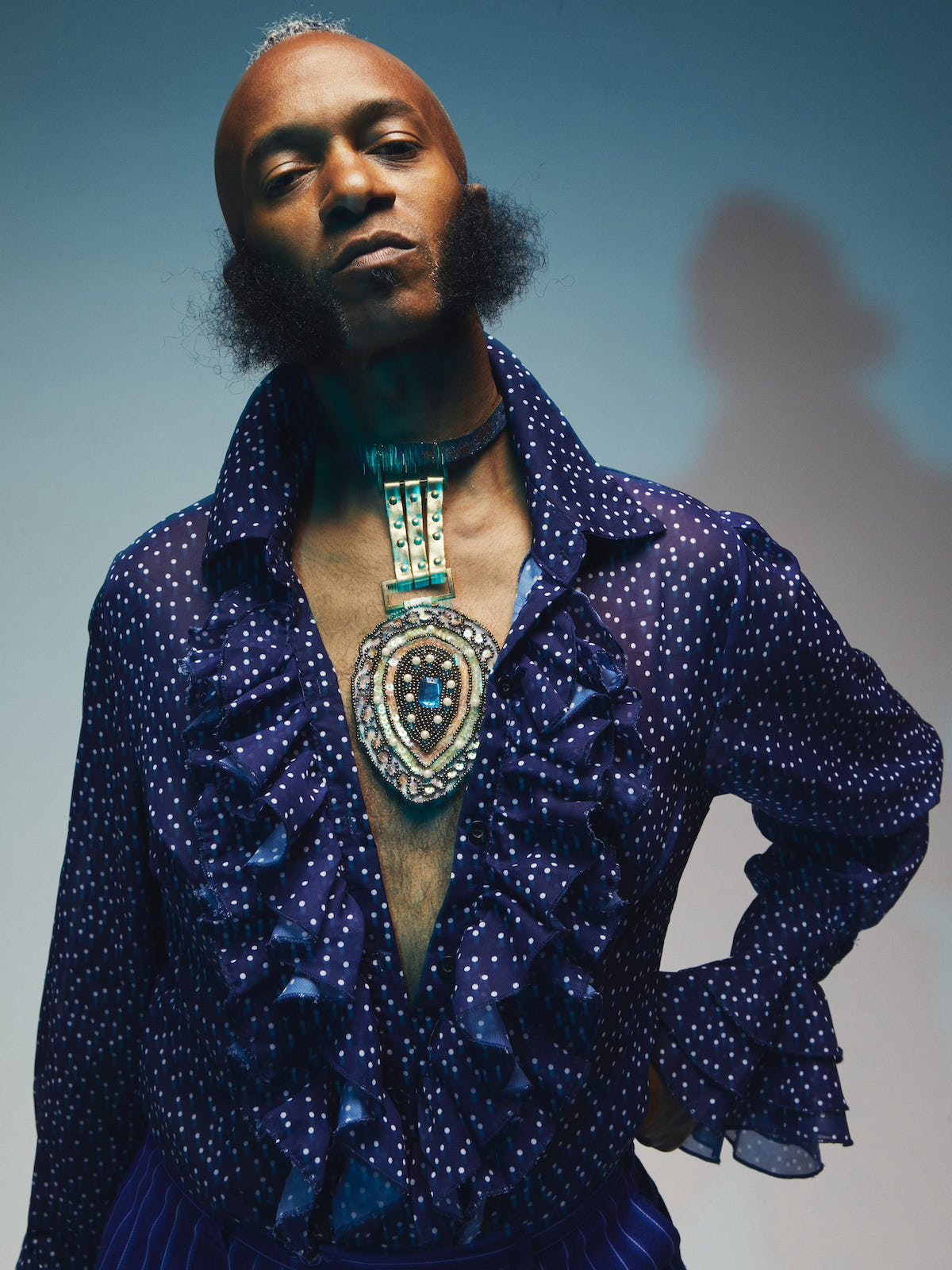

By now, much has been made of Negrito’s own unique story — his early years growing up in an orthodox Muslim household, the doomed major label deal that turned him off of the music industry altogether, the near-fatal car cash that permanently damaged his guitar playing hand — as well as the remarkable redemption arc that began in 2015, when he won the first NPR Tiny Desk Contest. In the years that followed, Negrito would go on to take home three consecutive Grammy Awards for Best Contemporary Blues Album, tour with everyone from Sturgill Simpson to Chris Cornell, collaborate in the studio with the likes of Sting and E-40, launch his own Storefront Records label, perform at Lollapalooza, Glastonbury, Newport Folk, Bryon Bay Blues, and nearly every other major festival on the map, and found the Revolution Plantation, an urban farm aimed at youth education and empowerment. But the events on White Jesus Black Problems pre-date all of that by more than two centuries, and the story here isn’t so much Negrito’s as it is America’s.

“Looking back, I was struck by the number of parallels between their time and ours,” he explains. “Obviously we can’t ever really know what it felt like to be someone else’s property, but there are a lot of things I think we can all relate to here: the consolidation of wealth and power in the hands of a privileged few, the dehumanizing treatment of anyone who looks different or comes from someplace else, the pitting of poor people against each other. And yet, just like today, if you look in the midst of all that chaos and hardship, you can find courageous folks doing courageous things, and I think that’s worth celebrating.”

Over the course of a little more than a year, Negrito wrote nearly 50 tracks inspired by Gallimore and Grandfather Courage, as he came to call him, eventually whittling the collection down to a mix of 13 songs and interludes that captured the struggle and triumph of the couple’s story. For the first time ever, he recorded the core of each song live in the studio with his drummer, James Small (who also plays Grandfather Courage in the film), before later layering up additional instruments on his own and bringing in outside collaborators like bassist Cornelius Mims, guitarist Masa Kohama, keyboardist Lionel LJ Holoman, and cellist Mia Pixley.

“I wanted the kind of organic feel that you can only get with a live drummer,” says Negrito. “I got really painstaking with the bass lines, too, crafting them note by note because they were so important to the songs. And then on top of all that, I started layering a lot of Moog synthesizer and an old Yamaha transistor organ from the ’60s because I felt like it brought a lightness to the sound. People hear this album title and they’re ready for you to break out the militant jackets, but this is a record about love and finding ways to use the past to heal the future.”

That duality is clear from the outset on White Jesus Black Problems, which opens with the mesmerizing Venomous Dogma. Blending choir vocals and sci-fi synths, the track begins with a dreamy soundscape meant to evoke the freedom and joy both Gallimore and Grandfather Courage may have known in their respective homelands. Then, roughly halfway through, there’s an abrupt and ominous shift as searing guitars and chain gang choruses take over; life in captivity has begun.

The fiery Highest Bidder mixes African rhythms with Delta blues as it examines a society where everything — even human dignity — is up for sale, while the dreamy Mayor of Wasteland interlude looks at the intersection of compassion and accountability, and the prog-rock-meets-soul anthem They Go Low considers the depths to which man will sink in the name of greed. “Even today, we worship billionaires while some parts of this country look like what we’d call the third world,” says Negrito. “We’re not at the table when the 1% are making their deals. We’re on the menu.”

A glimmer of hope emerges when the ecstatic Nibbadip rolls around, as the playful tune recounts the lovers’ meeting in details pulled from Gallimore’s arrest record for “unlawfully cohabitating with a negro slave.” “They dragged her into court / On May 4th on a cloudy rainy day,” sings Negrito. “Told her love’s against the law to my grandpa / In Amelia County, VA / He said please don’t sell me / No I’m in love with a woman / Freedom’s in her eyes.” From that moment, the record seesaws between the power of love and the love of power, between the promise represented by Courage and Gallimore’s defiance and the weight of the system meant to crush them. Negrito channels Freddie Mercury on the aching Oh Betty, which wonders if love can survive seemingly insurmountable odds, and lands somewhere between James Brown and Black Sabbath on the desperate Man With No Name, which transforms frustration and exhaustion into a fierce determination to survive.

Despite the ever-looming and distinctly American darkness that threatens to descend at any moment (the brutal You Don’t Belong Here interlude will sound all too familiar in the age of racist rants caught on video, and the Kinksian You Better Have A Gun shines a light on the violence woven into the fabric of our society from the start), love refuses to surrender. The jittery Trudoo finds liberation in self-determination; the dizzying In My Head revels in the transformational art that can emerge from oppression; and the rousing closer Virginia Soil offers up its gratitude for the sacrifices of those that came before.

“I stand on the shoulders of my ancestors, both black and white, who showed me that anything is possible,” says Negrito. “There was a lot of ugliness in their story, but there was a lot of beauty, too, because in the end, perseverance overcame.” Ultimately, that’s what White Jesus Black Problems is all about. “They won,” says Negrito. “Love won.”