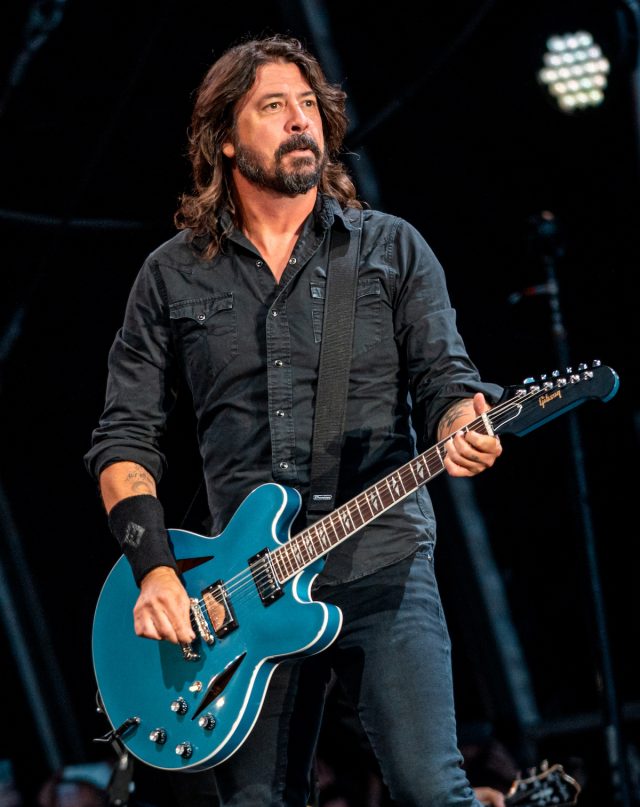

For years now, people have called Dave Grohl the nicest guy in rock. Near as I can tell, they’re right. I was lucky enough to get some phone time with the former Nirvana drummer-turned-Foo Fighters founder and frontman back in 2011. Here’s how it went:

Dave Grohl has reached a new level of Nirvana. After 15 years of ups and downs with Foo Fighters, the grunge icon-turned-arena rocker claims he’s on cloud nine these days.

“In all honesty, the last eight months have been the best eight months this band has ever seen,” the jovial Grohl enthuses from California during a rare day at home. “It’s fucking crazy.

“After making this album in my garage, going out and seeing the reception that we’re getting to the new stuff, and the size of the audiences, it’s shocking. It really is. We didn’t aspire to these new, lofty heights. We just wanted to play music. I mean, don’t get me wrong, I’ll fucking take it. It’s fucking awesome. I don’t have any complaints at all. But it’s strange when you see things just get better and better. It’s not really supposed to happen that way.”

It sure didn’t start that way. When Grohl launched the Foos as a one-man band in 1995, he was simply trying to regroup after the devastating suicide of Nirvana bandmate Kurt Cobain. Easier said than done. As chronicled in the recent Foos documentary Back and Forth, the band and Grohl have endured their share of well-publicized growing pains, including lineup changes, scrapped albums, near-breakups and the near-fatal overdose of longtime drummer and best friend Taylor Hawkins.

But what didn’t kill them, etc. After years of compartmentalizing his past, Grohl has begun to embrace it — welcoming erstwhile Nirvana/Foo Fighters guitarist Pat Smear back into the lineup, reteaming with Nevermind producer Butch Vig and bassist Krist Novoselic on the energized homemade Wasting Light CD, and openly airing all the band’s triumphs, trials and tragedies on Back and Forth.

In this exclusive Canadian interview, the motor-mouthed 42-year-old frontman comes clean on the endless road (which briefly brings the Foos back to Canada this week), trashing the dressing room, and seeing his life flash before his eyes.

The album has been out for a while now. You’ve played the new songs dozens of times. The first big rush is over. But you’ve still got a year or more of touring ahead. Is this where you start to think, ‘What did I sign up for?’

That doesn’t really happen until about a year in. I’m not tired of it at all. We have this saying in the Foo Fighters: Home is the hard part. Getting out on the road and doing this for two and a half hours every night live; that’s kind of what we’re built for. As people, that’s what we’re designed to do. Then you home come and it’s like, ‘Wait; I have to do chores?’

You do chores? It’s an injustice!

I know, right? (Laughs) Nah, I’m just kidding. It’s a perfect balance, what we do now. We realized a long time ago that our life outside the band is just as important as our life inside the band.

You get that sense in Back and Forth when you see everybody’s families hanging out together. You’ve been taking that circus on the road too, right?

We actually had all the families out with us in Europe for about three weeks. And it was fucking chaos. It was awesome. Those kids can trash a dressing room faster than Van Halen. It’s fucking insane. The greatest is when you’re playing in front of 40,000 people and you turn around and all you see are these little day-glo headphones running around the stage beating on cowbells and tambourines and jumping on the drum riser. It’s fucking hilarious.

This tour has literally taken you from clubs to stadiums. Why was starting small important to you?

Because it’s different now. Back in the day, when we’d put out an album, we didn’t go straight to stadiums. We’d start in clubs. We had a bit of time to work up to the bigger shows — if we were even going to play them. But nowadays, we get thrown right into the headlining spot at a festival. You have to feel confident to do that. So we go into our tiny rehearsal space, which is actually an isolation booth — it’s maybe 12’ by 12’ — and the five of us cram in there with tiny amps and just jam as loud as we can until the ceiling is dripping with sweat. And this time, we ran through the entire record like it was a set list, from the first song to the last. And then we thought, ‘Let’s go out and play the entire new record in clubs before anyone’s even heard it.’ I remember having a meeting with management, and there was a lot of scratching of chins about the repercussions of doing the entire album in this digital age where everything goes straight to YouTube. And I went, ‘Fuck it. We’re proud of it. It’s a great record. it sounds good when we play it.’ And doing that really made us strong. So now, it’s a pleasure to play those huge shows.

You’ve spent a lot of years trying not to let your past overshadow your future. Clearly, you’ve become more comfortable with things; what happened?

When we first started, it was only about a year after Nirvana. There were lots of reasons why I didn’t want to talk about Nirvana. One was that Kurt died and he was a friend and it was still hard to talk about with anyone. The whole thing with the Foo Fighters was that I started this band to move on. To me, it was meant as something more than a band; it was a continuation of life in music. So for the first few years, I really wanted to give this band a little light so it would grow. I didn’t want to be stuck in the past. So with as much respect as I could muster, I was silent about Nirvana. Well, as the years went on, it became easier to talk about. And then after a while, I noticed people were coming to shows who didn’t even know I was in Nirvana. That was shocking. I’d talk to a kid and mention the drums and he’d say, ‘Oh, you play drums?’ I’d say, ‘Um, yeah, I used to be in this band called Nirvana.’ And he’d say, ‘You were in fucking NIRVANA?!’ I had just assumed it was always there right behind me, but after a while, it just kind of faded a little bit. So after years of thinking, ‘It’s too soon to work with Butch again,’ I started thinking, ‘Oh my God, it’s almost too late.’

Do you wish you’d done it sooner?

No. I wouldn’t have changed a thing with this band’s timeline, I swear. There are a few little hiccups I wish wouldn’t have happened, but all of the good and bad things have made us stronger.

Have all the events of the past year given you any closure when it comes to Nirvana?

I wouldn’t say closure. Because I don’t want it to end. I’m very proud to have been in that band. I don’t necessarily need any closure there. Losing a friend is something else. But the documentary and the album, that’s Foo Fighters territory. There might be some nostalgia there with Krist or Butch. But when I watch the documentary, I don’t think about Nirvana. I think about the Foo Fighters. I remember when we all watched it for the first time. We were sitting in a room, the lights went out and we watched the last 17 years of our lives. Then the lights went on and we just looked at each other and went, ‘What the fuck just happened?’ It’s like watching your life flash before your eyes, but you still have the opportunity to live. It’s pretty cool.