“Outside of a dog, a book is man’s best friend. Inside of a dog it’s too dark to read.”

— Groucho Marx

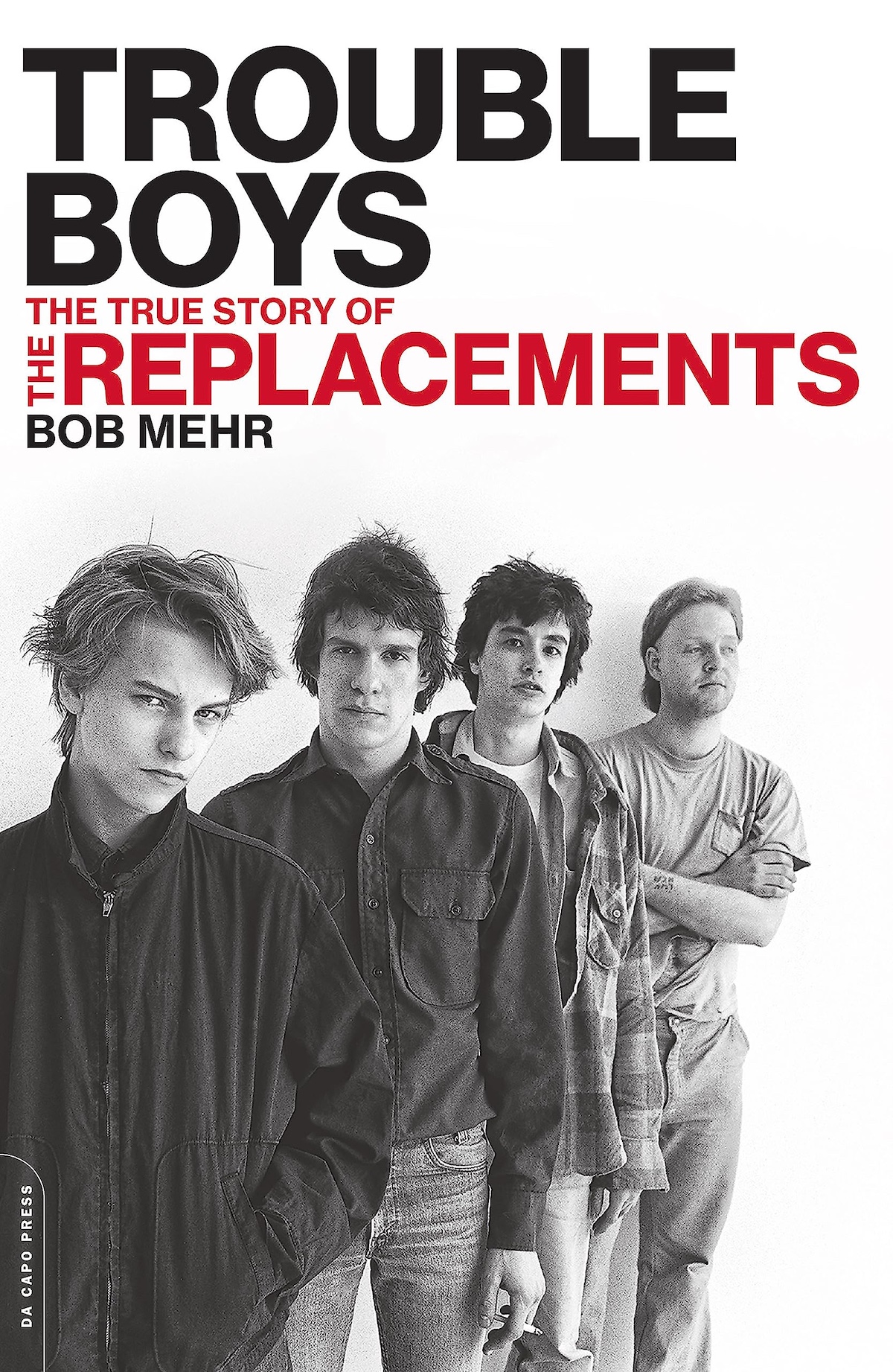

Two years ago in Goodwill I spotted a copy of the 2016 book Trouble Boys: The True Story of The Replacements by Bob Mehr on a shelf. I immediately thought to myself one single thought: Oh, fuck yes, I can resell that for a profit. So I paid my three bucks for it and went on my way. For a while after that it sat for sale in our booth at a local antique mall. Surprising to me, no one bought it. Then- strangely- I kept thinking about the book; thinking maybe I should keep it. Why though? I practically never read music bios anymore. Why would I want to have this one around? One day a few months ago when Arle was heading to the booth to restock, I mentioned to her that I’d like to have the book back. Can you bring it home? I said.

Two years ago in Goodwill I spotted a copy of the 2016 book Trouble Boys: The True Story of The Replacements by Bob Mehr on a shelf. I immediately thought to myself one single thought: Oh, fuck yes, I can resell that for a profit. So I paid my three bucks for it and went on my way. For a while after that it sat for sale in our booth at a local antique mall. Surprising to me, no one bought it. Then- strangely- I kept thinking about the book; thinking maybe I should keep it. Why though? I practically never read music bios anymore. Why would I want to have this one around? One day a few months ago when Arle was heading to the booth to restock, I mentioned to her that I’d like to have the book back. Can you bring it home? I said.

Sure, she said. And then she did.

It sat around after that. It sat around on various bookshelves downstairs in our house, edging up to the lip of dust that inevitably forms on the small cliffs separating the bindings and the drops. For most of the books I own, this is as close as they will ever get to me after that initial day I bring them home. They will see me walk by relentlessly, some for decades now, but most will find no satisfaction if their idea of a good time is actually being opened and read. Trouble Boys was no different, really.

The only things that maybe saved the book from its almost certain fate in the end are these.

First off, it’s fat and so it doesn’t fit well in a lot of our bookcases. This means it’s often laid on top of a row of books that do fit well, giving it, by random stroke of luck, a position where it stands out to me like a sore thumb each time I pass by which is probably 25 times a day minimum.

The second thing is that it’s a hardcover/ and I loathe hardcovers/ always have/ who the hell knows why/ but it’s probably because I’m poor and I have always been poor and paperbacks are the tomes of the peasant, now and forever.

The last reason the book got lucky as hell was the death of Slim Dunlap, one of the defunct band’s members, who died this past December at the age of 73. Slim’s death kicked me in a shin I hadn’t been kicked in for years. This band who had been so tremendously paramount to me in my teenage formative years, they’d been more or less abandoned by me now. My love and adoration had been replaced by apathy and a sense of awkward discomfort. Much like a vital vein in the very arm of the body of work they’d created, everything they’d mean to me/ everything they’d stood for and fought for in a world that doesn’t give a shit/ it had all collapsed. My immersion, my baptism, my 17-year-old stoner passion had retreated and in its shadow now lurked a feeling of being triggered instead of being lifted.

The Replacements, it turns out, had been replaced. Not by another band or even a different genre. But by silence. Quiet. No sound. No music where there’s had been. They’d almost singlehandedly changed my life, made me see rock ’n’ roll as something possible yet impossible at the same time as opposed to just fucking purely impossible from the get-go. Their existence had lent me hope as a kid.

And here’s the kicker.

That sentence right there? That is a sentence that I am absolutely certain would make Paul Westerberg, the band’s de facto leader, throw up in his mouth.

I began reading the book this past week. In the first few pages, I felt weird about it. Something in me had no interest in revisiting a story that I loosely knew. Their childhoods were not especially enchanted. In some cases, there was excessive abuse, the kind that ultimately ruins people. Or causes them to join bands. In examining why I have this kind of trepidation towards band bios (especially this one) I’d probably have to submit myself to a lot of laying under the microscope/ nude. Which no one really wants to have to deal with, I know.

But still, I remain certain that The Replacements, more than any other band in a long storied history of a kid who loved bands, they fucked me up. Not on purpose, I don’t think. Although I can’t speak for the surviving members. More likely, the idea of this music and the way it was presented to the world, or at least the small amount of the world who gave a shit about it when it was unfolding in real time, it reminds me now, at age 53, of a couple of, shall we say, slippery slopes.

The first thing that might have fucked me up when it comes to The Replacements is that I actually played in a real life band. For something like 25 years, from roughly 1995 to 2022, I really gave it my all. Hell, I gave it more than my all. I gave it my fucking soul. I allowed that beautiful beast of possibility which any unknown band truly is, I allowed that to live inside my skin, to flow freely down in my veins/ in and out of my heart. Marah, our band, was this cancerous gift that I have never understood and never ever will. For anyone not in the band, it was- at best- a good time. Good music to listen to, exciting shows to watch. Don’t get me wrong, we had some wildly devoted fans whose love of what we did (and whose gentle smiling at what we maybe meant to do) remains to this day one of the best things that has ever happened to me.

Too often, silly artsy-fartsy wannabes like me, we tend to look back at our lives with this pressing need to see the poetry in everything. When it’s done well, it can be magical. That’s sort of what The Replacements did in the end, I think. But when it’s done all shitty like, well, the results are straight up horrific. Which puts me at death’s door here in a way because I know I am no Paul Westerberg and I also know that I remember a time when I laid in my bed at night and I desperately, desperately wanted to be.

Rock ’n’ roll doesn’t work like that though.

And that’s the first hard lesson most of us who have thrown ourselves to the proverbial woods had to learn. Like many of the people who actually play or played in bands, the actual transitioning from being a radical fan and lover of other bands to being in your own band is way more challenging and mentally taxing than it probably seems. In my case at least, the unbridled/ very real joys of playing rock’ n’ roll across several decades for people (two or five or 11 or 124) who actually wanted to see you- and were willing to actually PAY for the opportunity- might have permanently disabled a former (essential) part of me. All of that work and travel and relentless convincing myself that it was all worth it somehow (or that it would be one of these days), it was also this kind of a… how can I put this without sounding like a dick… well, I’ll just say it. It was also kind of a setup. A sham. A bamboozle the likes of which many if not most people who have never been in a band could ever fathom.

The truth is, bands- like coffee shops and record stores- are absolutely doomed to fail way more than they don’t. It isn’t rocket science. Glory is nothing but muscle car smoke. You can’t hold that shit in your greasy palms; you can only ever smell it. It rises from the summer blacktop over by the Dairy Queen, and you maybe whiff it a few times in a lifetime if you’re lucky.

Jack and Diane? Fuck yeah. They both bathe in that kind of mystical pollution.

But not you, hoss.

Not you.

American triumphantism, obviously, is something we are sold from a young age. It’s all such a mess. We live for the dream of breaking out of mundanity and capturing the skyline because it all seems so beautiful and breathtaking. That sliver of luck just seems so mesmerizing.

But in all actuality the stuff is legend and it’s not even really there to be had in the first place. Think of the American Dream, or in our case, the more streamlined vision of being in a ‘successful’ band and ‘making it’ kind of like one good old fashion cowboy. I’m talking John Wayne. On the silver screen, and later on reruns in the middle of the night, he was larger than life, a bear of a man, tender and tough, who could squint a burning hole into an Indian’s forehead or charm a lovely prairie virgin with a single sexual grunt from the top of his trusty horse. However, in real life, you were never, under any circumstances, ever, ever, ever going to belly up to the saloon bar and actually encounter that hero. Why? Because he was fake. He didn’t exist. He never had before and he still doesn’t now. The closest you would have ever gotten to a run-in with the small reality of John Wayne the man propping up John Wayne the towering fantasy would be something like this:

Here’s John Wayne hollering at you, til he almost pops a vein in his neck, not to open the bathroom door because he’s in there trying to take a crap but nothing is happening. And even though you just want to make contact with your hero and know it’s now or never, the man on the others side of the door is frustrated and pissed off. He screams at the knob when you try turning it.

“Back the hell out of here, pilgrim, before I shoot you through this door and leak the sad story right out of ya!”

And I get that maybe that is an extreme attempt at trying to explain the not-so-fine line between loving a band in the spectacular sunset or losing them in the sudden storm, but that’s all I’ve got, I guess. Look, there is no actual metric for what it means to succeed in a band. In the mid to late 1990s, as our band was being born, the music industry was literally on the verge of being stabbed repeatedly in the eye by the dirty alley dagger of a little up and coming outlaw known in small circles as El Interneto. No one could have seen him coming and who cares anyway. The music industry, as a whole, had always been a colossal ghost ship sailing the seven seas with a cargo load of stank and plague.

The coming era, the one that would essentially witness the destruction of a once-in-a-lifetime band like The Replacements only to conjure up their somewhat unexpected (possibly unneeded?) resurrection, was about to set fire to most of the rock-n-roll playbook that had been written up til then. And it’s worth noting here that that part of all of this doesn’t really interest me either. I don’t ever spend even 20 minutes wondering what might have been if the world had spun this way or that way. To do so would be a monumental waste of my own time. And to write about it would be a waste of yours.

My rambling point is to try and show you how I used to be this scrappy, lovable 15-year-old kid staring out the school bus at my suburban October landscape. Alex Chilton and I Will Dare on my Walkman. There was this dimming light of an encroaching autumn slashed purple streaks across my shining eyes. I was so alive, dude, so alone, and yet so in congregation with the music in my world. With the bands I loved and with my friends who also loved them, I set out on a journey towards what felt like the only way forward for me.

But I was wrong.

Or was I?

To read the rest of this essay and more from Serge Bielanko, subscribe to his Substack feed HERE.

• • •

Serge Bielanko lives in small-town Pennsylvania with an amazing wife who’s out of his league and a passel of exceptional kids who still love him even when he’s a lot. Every week, he shares his thoughts on life, relationships, parenting, baseball, music, mental health, the Civil War and whatever else is rattling around his noggin.