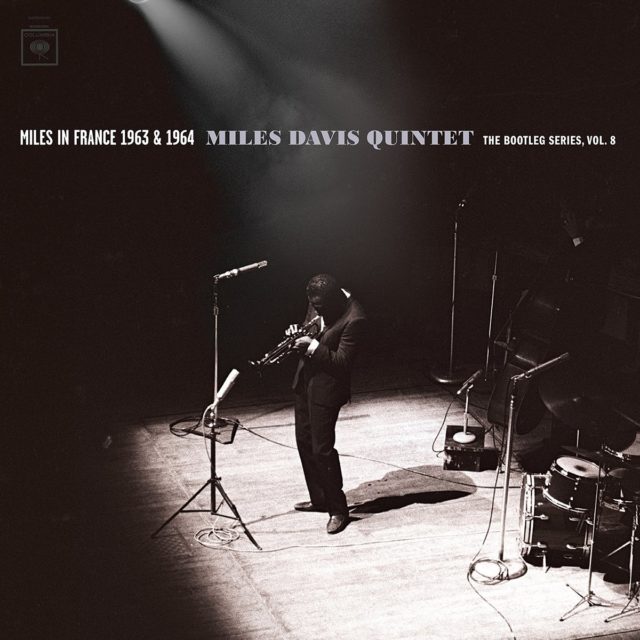

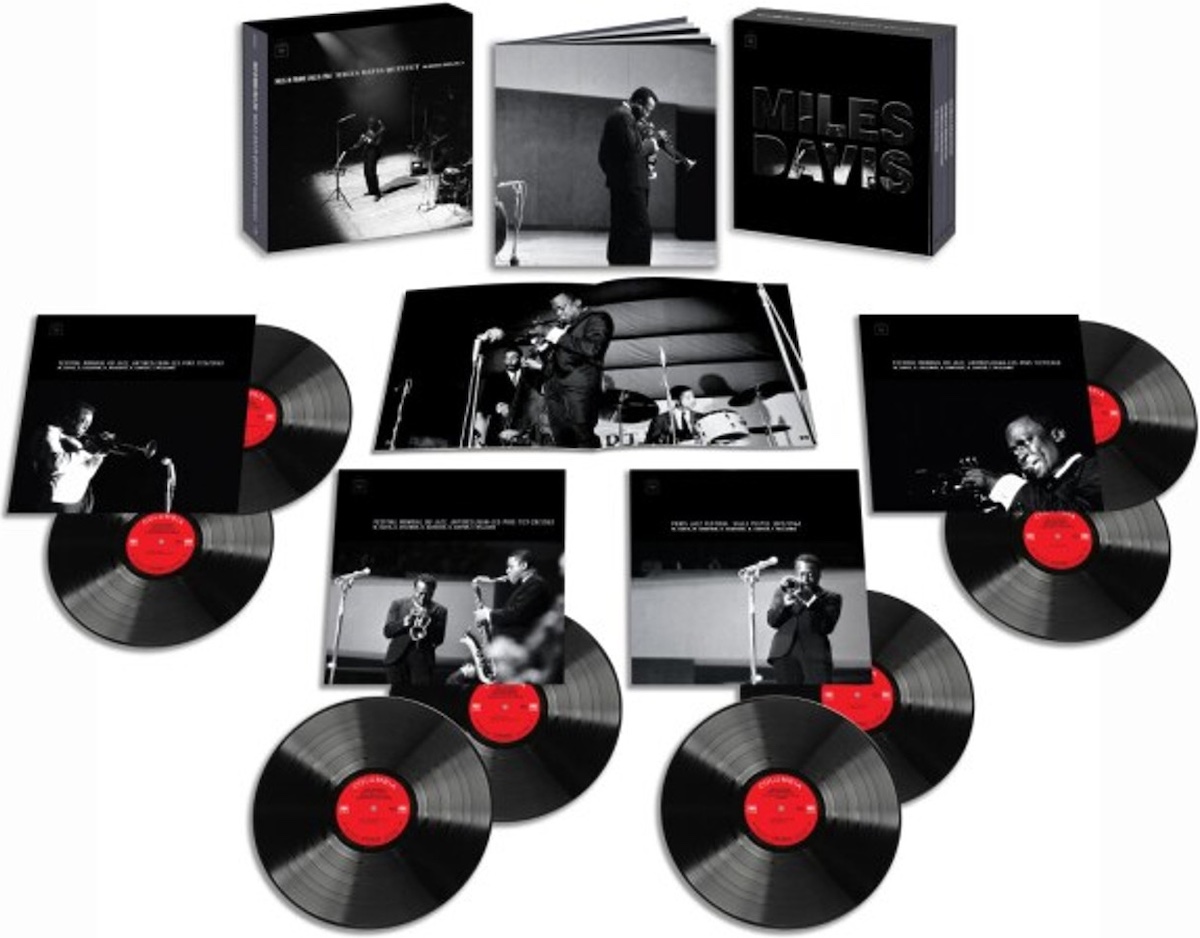

THE EDITED PRESS RELEASE: “The acclaimed Miles Davis Bootleg Series has spanned years as early as 1955 and as late as 1985, but it has not yet touched 1963 or 1964 — a pivotal period in Miles’ musical evolution and the auspicious beginnings of the Second Great Quintet. Miles in France 1963/64: The Bootleg Series, Vol. 8 includes performances at the 1963 Festival Mondial Du Jazz in Antibes and the 1964 Paris Jazz Festival. The 1963 recordings feature George Coleman, Herbie Hancock, Ron Carter and Tony Williams, while the 1964 recordings feature Wayne Shorter’s arrival on tenor saxophone.

France was important to Miles on both a professional and personal level, quickly becoming his preferred live market. He played in France more times than any other country outside the U.S. and recorded there frequently. His history in the country begins 1949 — when he appeared at the Festival International De Jazz at just 22 years old — and ends in July 1991 at a concert in Nice just two months before he passed.

In the early 1960s, Miles came to France having altered the course of jazz. His 1959 landmark album Kind of Blue eschewed hard bop for a modal style that allowed room for a freer type of improvisation — an overcast slow-burner evoking ease and tension. Compared with Kind Of Blue, the music coming out of the quintet in Antibes and Paris had very little room for space and silence. The highs were dramatic and the lows were filled with powerful phrasing, adding fresh perspective to this landmark album in all of jazz.

Miles hired the rhythm section of Hancock on piano, Carter on bass and Williams on drums in spring 1963, and they went into the studio in May of that year with Coleman on tenor sax to record the second half of the Seven Steps To Heaven album. Two months later they arrived in Europe.

Carter recalls the experience in the liner notes, adding, “I had never played with anyone like that, of course, and certainly not for this extended period of time. It was just stunning to hear him play like this, play with that intensity, play with that tempo, play with that direction night in and night out and not turn it on to the band and say, ‘Stop that.’ He allowed us to do whatever the chemist allowed his proteges in the lab to do. ‘Take these chemicals I’m giving you guys and see what we come up with. Just call the fire department if necessary.’ ”

Miles would return to the U.S. with a new sense of purpose, spurred on by the bands he took to France. By the time he recorded E.S.P. with the quintet in 1965, he proved that — despite whatever physical and spiritual challenges he may have endured — he was the barometer by which jazz moved and evolved. Some 60 years removed from these recordings, and more than 30 since his passing, Miles is still the summit and pinnacle, the essence of audacity, the monument of all monuments.

Miles in France was produced by the Grammy-winning team of Steve Berkowitz, Richard Seidel and Michael Cuscuna (it was one of the last productions for Cuscuna, who passed away earlier this year), and it was mastered by Grammy-winning Sony Music engineer Vic Anesini at Battery Studios in N.Y.C.”