I bought Cheap Trick’s self-titled debut album a few weeks after it came out in 1977. I distinctly remember picking it up at the iconic Tower Records store on Sunset Boulevard in L.A. on an Easter vacation to the U.S. Like many (if not most) early fans, I was lured in by the cartoonish weirdness of the cover pic, the band name and that distinctive logo — it was all unlike anything I’d seen before. Of course, also like countless first-time listeners, I ended up being blown away by the oddball lyrics, powerhouse vocals, muscular beats and searing guitars in their sound, which was also pretty damn unique (at least to my teenage ears).

I also recall that they were opening for The Runaways at the L.A. Forum while I was in L.A. I didn’t get to see that show, sadly. But I did catch them that summer on their first Canadian trek, opening for KISS on the Love Gun Tour. I was already a massive fan; I suspect they made plenty more that night with their typically over-the-top performance. Since those days, I’ve seen them somewhere around a gazillion times, bought and/or reviewed all their albums, and interviewed both Rick Nielsen and Robin Zander. So naturally, I have been looking forward to American Standard: Cheap Trick From The Bars to the Budokan and Beyond, the new book by author Ross Warner.

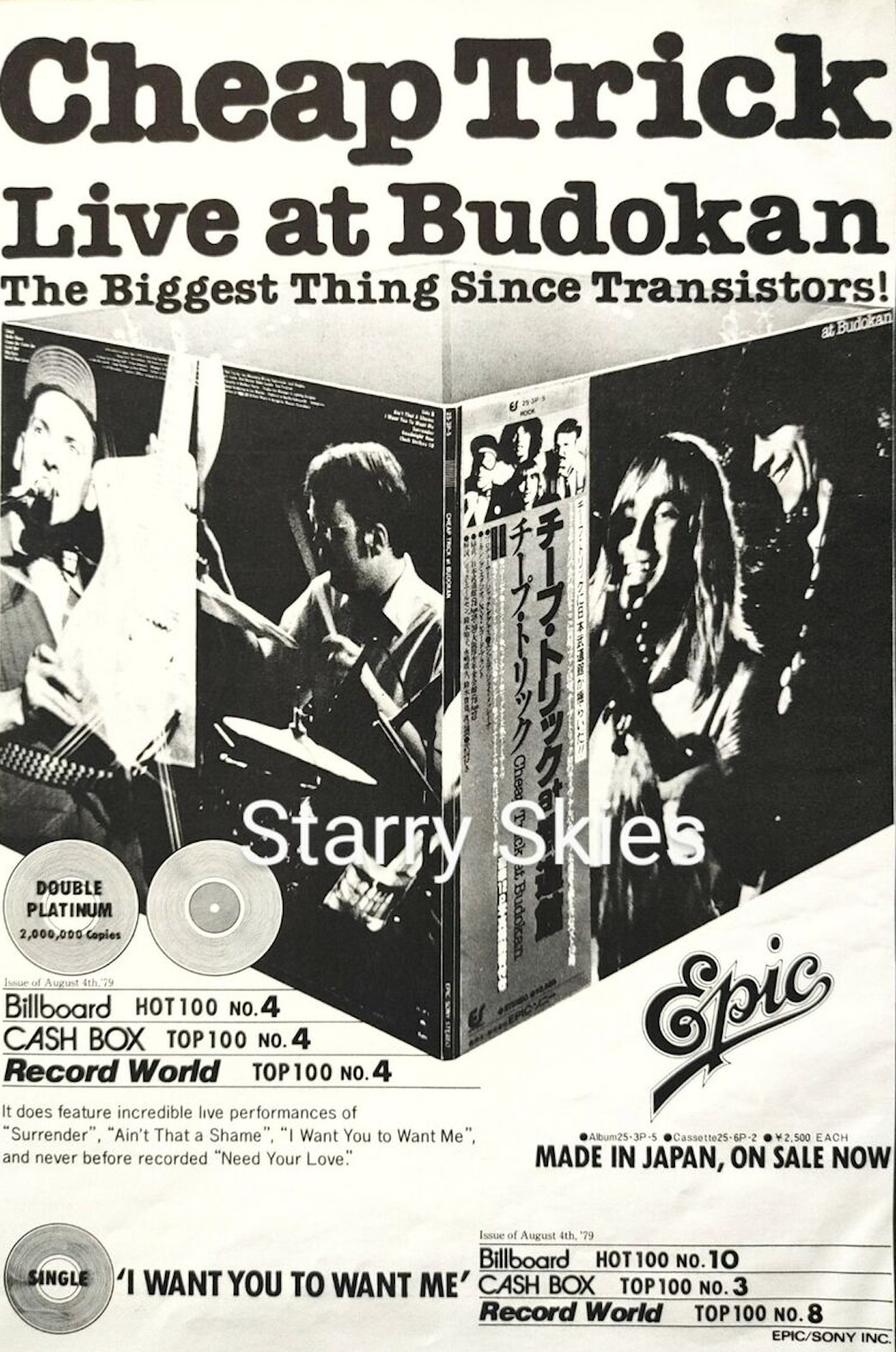

After I included a preview blurb about the book in a roundup a few weeks ago, Warner was kind enough to send me a review copy — and to let me run this excerpt about the band’s landmark Japanese tour and the recording of their breakthrough live album Cheap Trick At Budokan. Suffice to say, he’s all right. Roll some numbers on the couch, get your KISS records out and enjoy:

GO EAST, YOUNG MEN, FOR THE ACCIDENTAL OCCIDENTAL INVASION

In March ’78, the month before they left for Japan, Cheap Trick was featured in Hit Parader. Jim Girard’s interview with Rick Nielsen addressed the intentionally fuzzy history of the band that began with Eric Van Lustbader’s Epic bio: “I don’t think it really matters what we’ve done up until now,” Nielsen said. “Maybe once we have the credibility as a band, then some of that might matter. There are a lot of interesting stories and a lot of old musical ideas that we have. It’d be a treat to hear that people would really care about our past, but right now we mainly talk about what we’re doing now.”

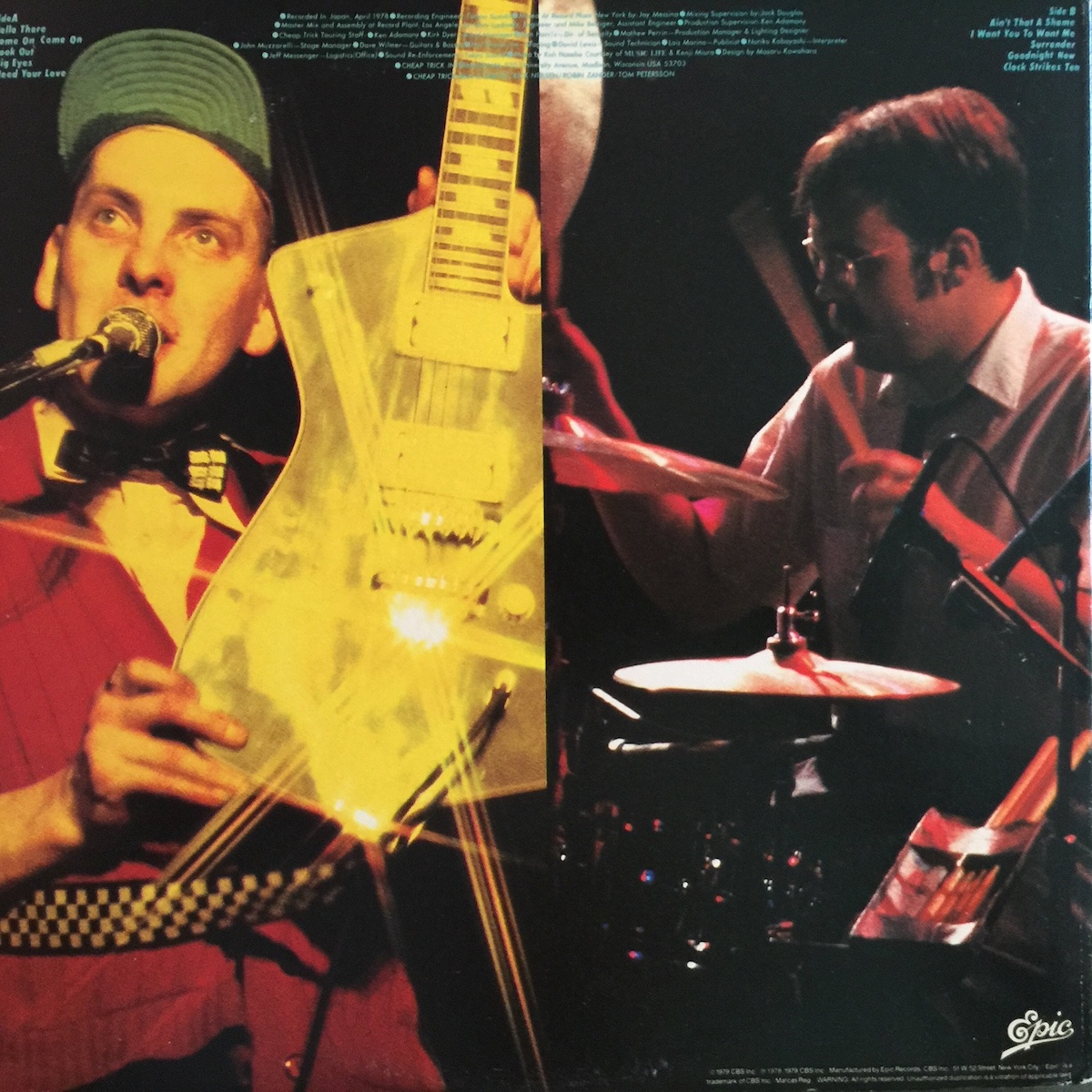

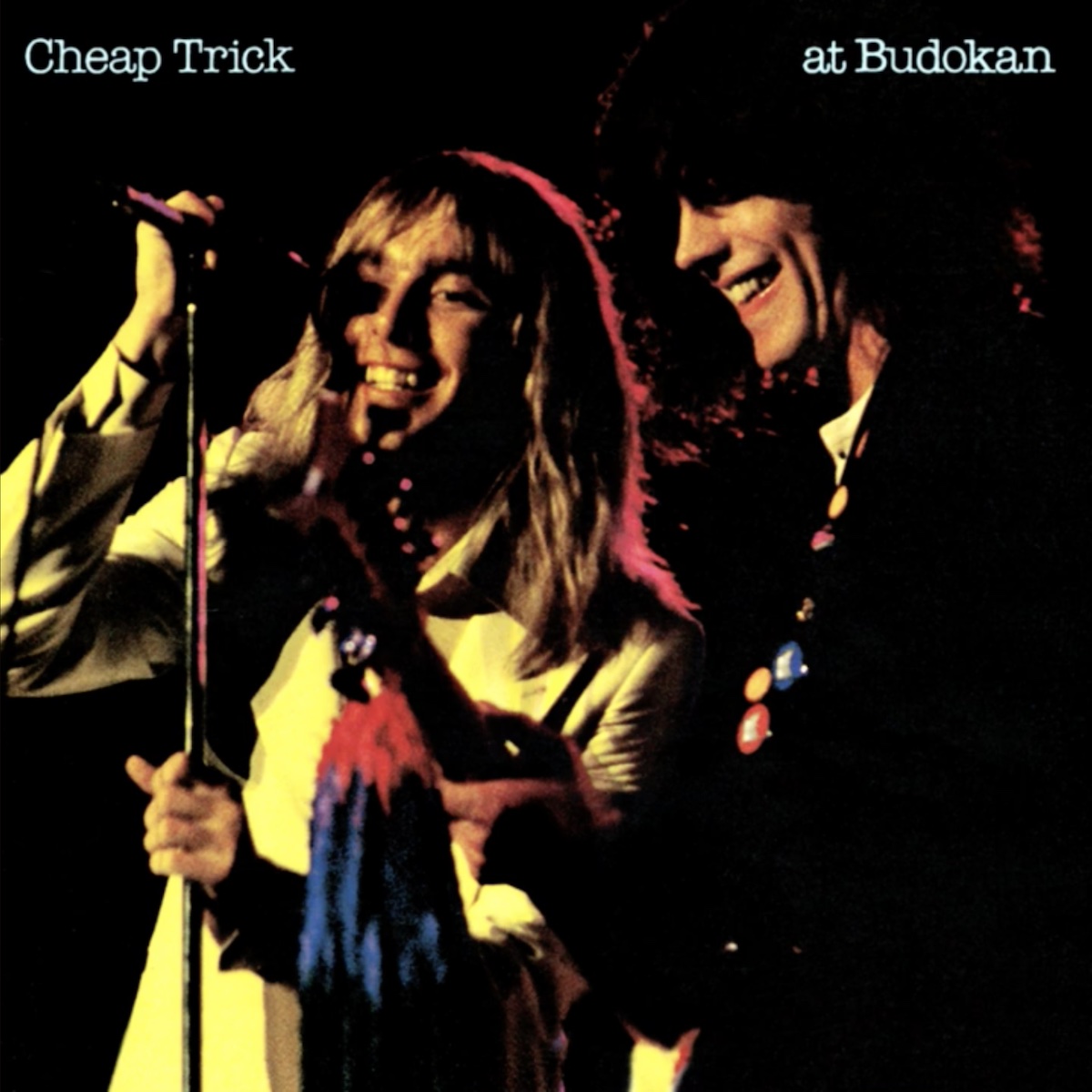

Nielsen, who would receive a dozen custom-built Japanese guitars as gifts upon reaching Tokyo, had an entire page of the commemorative tour book dedicated to his handwritten guitar inventory up to that time. One of these, a blue Greco with “I KNOW YOU LIKE IT” (a line from the 1970 adult film Mona: The Virgin Nymph) inlaid on the fretboard, appeared in Nielsen’s hands on the cover of Cheap Trick at Budokan. The stage lights, however, made the blue guitar appear white in the picture of Rick and Bun on the back of the album. Nielsen also owned a Gibson Les Paul Junior with the same inscription; he had that dirty-grandpa sense of humor long before his own kids were out of elementary school.

Robin Zander, whose life would change the most after returning from Japan, recalls how many interpreters were needed over the course of the visit. Like a game of telephone, he suggests, things would change slightly with each exchange. In many ways, that phenomenon explains how the legend of Budokan grew beyond the concerts themselves. However, the one thing that is undeniable is that the band was completely floored by the reception they received from the moment they touched down in Japan.

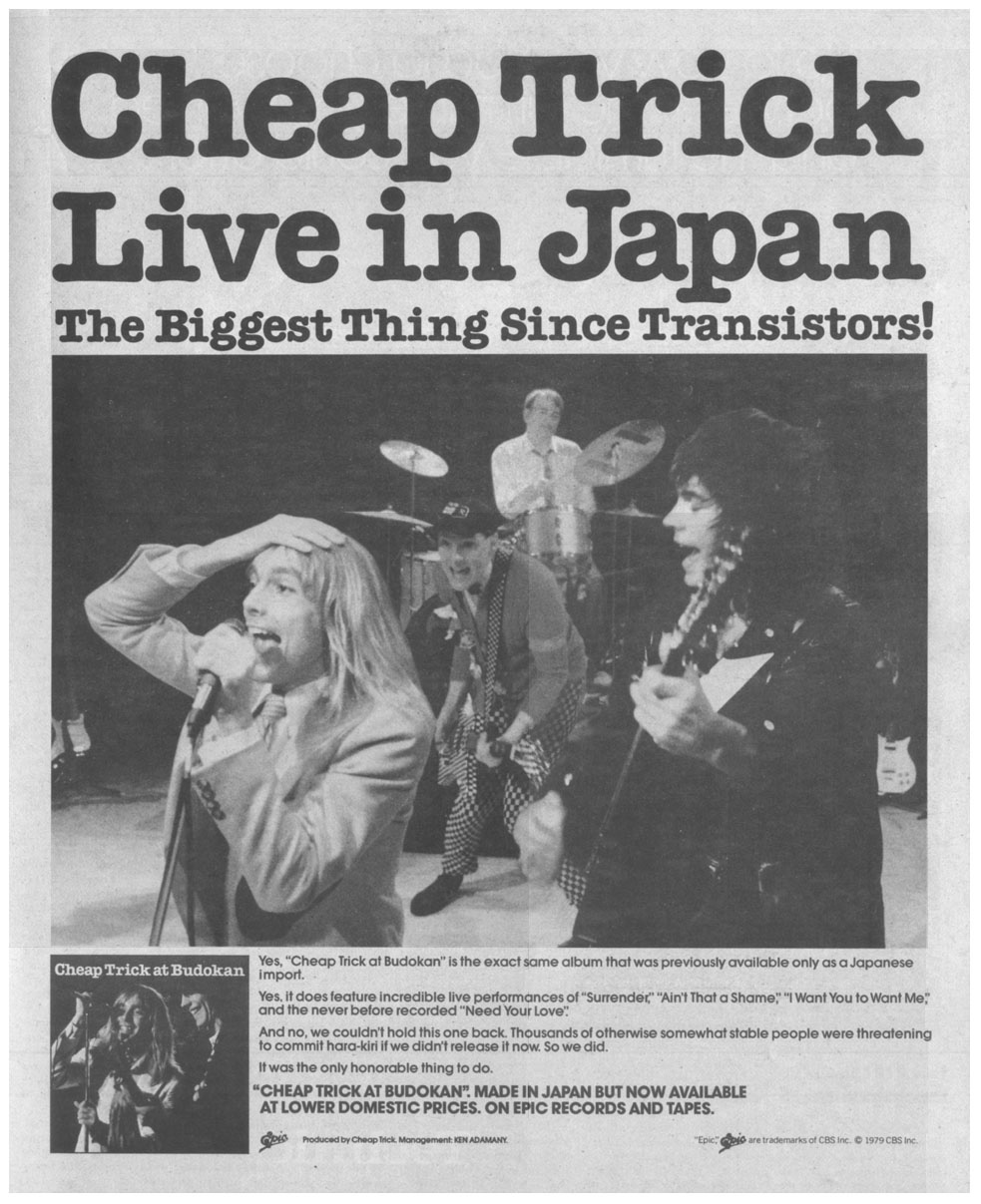

Japan Airlines (JAL) delivered Cheap Trick via Flight #1 at 4:45 p.m. on April 22, 1978. CBS Records staffer Lois Marino, the official tour publicist, dispatched through telex the unexpected and unplannable events that followed. Official photographer for the shows, Bob Alford, recalled, “It was just like Beatlemania. Gangs of Japanese fans were chasing them everywhere trying to rip their clothes off. I remember girls hanging out of the side of high-speed taxis taking photos, risking life and limb. It was nuts!” Koh Hasebe, who had also photographed The Beatles during their visit (and whose photos would appear in Cheap Trick at Budokan’s album art), remembered that even the huge numbers of kids at the airport didn’t stop Rick from tossing them the guitar picks in his pocket. Over the years, Nielsen has said countless times that Cheap Trick made the Budokan famous, and vice versa. Norio Nonaka is often credited as “The Man Who Created Budokan,” which would make him the guy behind the guys who made Budokan famous. Nonaka said he didn’t want the band to leave the hotel, to preserve a clean-cut image for the fans. Security guards were dispatched by promoter Daniel Nenishkis of Ongakusha Company, Ltd. However, it quickly became clear that Nielsen, Zander, Tom Petersson, and Bun E. Carlos needed to stay put for their own safety.

Lois Marino’s telexes to Susan Blond reveal that the “Beatlemania” claims were accurate. The band couldn’t walk two steps from the hotel without being mobbed. They traveled in trucks lying down with blankets draped over them, and fans still knew they were in there. They could finally afford to get two hotel rooms instead of one, though they weren’t paired as they were on the album covers. Robin and Bun E. were in one room and Rick and Tom in the other. The arrangement was a shake up from the “hunks / hicks” dichotomy. The band was told not to peek outside for fear that fans would wander back into oncoming traffic to get a better look at them. The touring party had its own floor with security at every available exit. Cheap Trick was showered with gifts, including those dolls made in their likenesses. Ken Adamany’s typed schedule for the band’s first full day in Japan included “sound rehearsal to be held at” with “some gymnasium” handwritten in. His photo of the band on April 23, shot through a window, seems to confirm the rehearsal location.

The band’s last show before Japan was on April 2 at the Roundhouse, and the 20-song set has a lot of similarities to what was considered for the Japanese shows. The London set had twenty songs and included first-album tunes like Taxman, Mr. Thief, Oh Candy and He’s A Whore. Clock Strikes Ten served as the encore, just as it would both nights at the Budokan. On April 7, Adamany wrote Daniel Nenishkis a letter with a list of 22 songs he said would be performed at the shows. Notable is the inclusion of Top Of The World, Stiff Competition, On the Radio, Hot Love and Oh Claire. Some of these songs would appear on the upcoming album, while Hot Love from the debut had sadly been dropped from the set. On Adamany’s list written in Japan, Taking Me Back from Heaven Tonight is crossed out for In Color’s Oh Caroline. Please Mrs. Henry was also struck from the final list, with Ain’t That A Shame (which appears on Adamany’s letter to Nenishkis) included. Norio Nonaka knew that Clock Strikes Ten and I Want You To Want Me would be hits in concert since both were already gold in Japan. A “souvenir album” and television special were already negotiated, so picking a setlist that matched was paramount. Epic Records Japan wanted three “new songs” for the set, which was how Ain’t That A Shame made the cut. To fulfill the label’s request, Lookout, a song recorded for but left off their debut album, was added, as was Need Your Love (which would appear on 1979’s Dream Police). I Want You To Want Me would be performed at all six Japan shows.

Over the years, Nielsen, Zander, and Petersson have told various versions of the folktale that I Want You To Want Me was added at the last minute to lengthen their set. Much like the improbable details of Eric Van Lustbader’s “band with no past” bio, it is amazing how often that story is repeated — especially since the song had just been performed in two high-profile gigs, one of which was broadcast on British television. The band, however, sometimes lets the truth out when pressed by those who probably know the truth anyway. Nielsen told writer Jeb Wright on Budokan’s 30th anniversary in 2008: “It is half true, and half story. We quit playing it in the United States. It came out as a single, and it didn’t get enough airplay to keep doing it. It was our silly pop song — I wish I could be that silly and stupid more often. For Japan, we had to do it, because it was one of the songs that was a big hit over there. Songs don’t resurrect themselves. It just doesn’t happen, where a song comes out, and a few years later it becomes a hit.

“We brought that out sort of as our last hurrah for the thing. Lo and behold, it took off. The United States started getting the live version from Japan instead of the studio version. I think the Budokan stuff is kind of interesting because it happened the back-ass way around. We had to go to Japan to be known in Chicago.” When asked by Wright whether they ever defied orders to stay in the hotel during that first tour, Rick said “Of course we did. ‘You can’t go there’ makes that the first place you want to go. We didn’t sneak out too often. We had never been there, and we spoke no Japanese at all. We really stood out.”

Of course, Nielsen will still tell the “last-minute addition” story, depending on the audience. For instance, he unspooled it to Howard Stern on April 8, 2016, right before their Rock And Roll Hall of Fame induction, when Cheap Trick appeared minus Carlos. Like all Cheap Trick tales, it’s a great story and retains the improbable nature of their Budokan breakthrough.

As Ira Robbins points out, like parents’ tales of Santa to their kids, or the fictionalized Beatles in their two feature films, “there’s a truth beyond the self-created myth.” The band knew I Want You To Want Me could be a great song; Robin McBride of Mercury Records tried to sign them in 1975 based on the strength of that song. However, the In Color version represented their flat-out pandering to radio. It wasn’t really played live much after the fall of ’77 as a result. As it happens, French singer Niko Flynn released a contemporaneous cover, translated to J’attends Toutes les Nuits (I Wait All the Nights). That version has, according to Carlos, “got a couple of changes in the chorus that we didn’t have, that we actually use on the line ‘Cryin’ — the chord steps up. We got that from his version.”

Adamany’s copy of the official tour press schedule from the 23rd (typed on Keio Plaza Hotel stationery and with the “Again, This Means You” warning) lists the rehearsal for the television special at 4:30 (the first Budokan show was filmed), dinner with the promoters at 8:30, and a radio interview and photo session at the hotel an hour later. There is also an interview with “our pal” Shibutani Yōichi of Japan’s ROCKIN’ON JAPAN magazine and an accompanying photo session. The magazine isn’t often mentioned in the Budokan story like Music Life and Ongaku Senka. However, it was the first Japanese magazine to cover the band, who gave several candid interviews that Steve Harris has made available on YouTube. Unlike the other two magazines, ROCKIN’ ON JAPAN made it through the following decades (like Cheap Trick) and is still in print today.

On April 24, the band flew from Tokyo to Fukuoka for the first show; Adamany’s itinerary places them at Hotel Nishitetsu Grand. The following day, they flew to Nagoya. By this time, they had a sense of the insanity that surrounded them, even though the concerts weren’t being professionally recorded yet. The Japanese audience loved the songs from In Color and, on the first night (April 25), shocked the band when they screamed back the “cryin’, cryin’, cryin’ ” refrain of I Want You To Want Me.

Cheap Trick’s second show, held in Nagoya, survives through a hard-to-find partial audience recording. After the studio version of the not-yet-released Oh Claire plays over the PA, polite applause is heard before Dyer’s booming intro. The song was also listed on Adamany’s April 7 letter. Though the band didn’t play Heaven Tonight’s hidden track Oh Claire that year, they kept coming on stage to the studio version. Adamany did end his letter to the promoter by saying that the actual sets were not limited to the list and / or wouldn’t be in that order. The recording provides clear audio evidence of the venue’s intimacy.

The Osaka show on April 27 was professionally recorded, though it, too, only exists as a partial pull from the crowd. Festival Hall was also smaller than the Budokan, but crowd reaction gave the band a vivid preview of what their audience response might be on the following two nights. The first night at the Budokan, which was filmed, shows Nielsen cupping his hand over his ear in preparation. The version of I Want You To Want Me that’s now synonymous with Cheap Trick was, indeed, recorded at one of the two Budokan shows and not in Osaka.

Along with the false story of their meeting Jack Douglas in the bowling alley, and apocryphal accounts of their signing with Epic, Cheap Trick fairy tales continue — because it seems like the truth doesn’t do it all justice. As Petersson said to writer Greg Prato, “So it’s always something that is a surprise, I’ve found — like that live record. And it shouldn’t be a surprise, because that’s how we were signed to a record label — people saw us live, and that was a strong suit of ours.” In Robin’s words, “It just had to be a moment in time and the energy of it and the fun of it and the kind of absurdity of it.”

Although the world would only hear the poppiest parts of the shows, which most delighted Japanese record buyers, the band performed much of their harder-edged material as well. Front of house mixer David Lewis had been working with the band for a while now, trying to improve their stage sound. He suggested that Epic/Sony boost their setup volume, but he couldn’t have anticipated how loud it would be. Osaka was a much better venue acoustically, although engineer Tomoō Suzuki was so stealthy, the band didn’t notice him. “We knew [the recording engineers] were supposed to be there, but we never saw them, even during soundcheck,” Adamany says. “I remember saying, after the concert, ‘Wow, great show. Too bad they didn’t record it.’ And then, all of a sudden, on stage-left. The door opens, and there’s a room with two 24-track machines and three guys. We had no idea they were there.”

Afterward, Suzuki recalled, “I packed up the equipment at 11 p.m. and headed for Tokyo in my car. It’s about 550 kilometers from Osaka to Tokyo. I reached Tokyo at 5 a.m., slept for two hours, and then entered Nippon Budokan to begin setting up.”

Norio Nonaka would claim that he only saw two songs at the Budokan over fears about the recording. While running to check with Suzuki, he was tripped by a security rope and flung to the ground. Once Nonaka was told everything was fine with the album, he went to the hospital to get stitches on his chin.

While there were undeniable flaws with the multitrack recordings, which would become evident once the band returned to the States, Cheap Trick’s magic was captured nonetheless on the tapes. Carlos even made his own audience recordings, to prove to his family how crazy the shows were. Nielsen told Jeb Wright that back then, “going to Japan was like landing on the moon. Back then, it was all Japanese people. We stuck out like a sore thumb, or a sore Illinoisian.”

Learn more about American Standard at the book’s Facebook page.