It had to be one of two things: Either someone really knew what they were doing, or it was all dumb luck. Smart money’s on the latter, I’d say, but I’ve got a stubborn heart that refuses all that.

It had to be one of two things: Either someone really knew what they were doing, or it was all dumb luck. Smart money’s on the latter, I’d say, but I’ve got a stubborn heart that refuses all that.

Oct. 26, 1964 was a dank regular Monday in San Francisco the day that Fantasy Records co-founder Sol Weiss hit the record button on the tape machine. Historical weather charts indicate that the city was likely dealing with at least a bit of drizzle that afternoon. They also say that there was a lot of fog and smoke.

I’m not sure what they mean by smoke, but I guess it could have been coming from the cigs Vince Guaraldi was chain-smoking. Weiss, who’d co-founded the popular jazz label with his brother Max 15 years earlier, was in the studio to record the jazz pianist who — despite having won a Grammy by that point — was hardly a household name. Outside of the rather insular jazz world, Guaraldi, who was 36 at the time, was a talented, somewhat progressive musician who had known some decent success. Not much more, not much less. The music he was creating was good, but jazz wasn’t exactly competing with The Beatles. Guaraldi got by all right, but basically no one knew who the hell he was.

Then, almost overnight, everything changed.

Crossing the Golden Gate Bridge one evening in a taxi, a TV producer by the name of Lee Mendelson was staring out the window and listening to the radio station that the cabbie had on when he happened to hear a song, a piano-based instrumental, that took his breath away. It was 1963 and Mendelson had been given the task of finding the perfect music for a planned documentary about Charles Schulz, the famed cartoonist who had created the immensely popular Peanuts comic strip.

This song, he’d felt right away, was the precise sort of music that the film needed. But there was just one problem. He didn’t know who the artist was and the DJ never said.

As soon as he got home Mendelson reached out to a friend, the esteemed jazz critic Ralph J. Gleason, described what he had just heard (probably hummed a bit into the receiver/ I like to think), and was handed the keys to the kingdom.

“Oh yeah,” Gleason told him, “that’s Cast Your Fate to the Wind, by Vince Guaraldi.”

“You want me to put you in touch with him?” asked the critic.

“Yes, please.” Mendelson responded. “Yes I certainly do.”

Guaraldi, by all accounts, got a phone call sometime shortly after all that. He was told by Mendelson that he could create the soundtrack for the documentary if he wanted the gig.

Guaraldi, a jazzman who’d been around the block a time or two, didn’t need time to think it over. He took the gig. He met with the television folks and he eventually met with Shulz himself. Everyone was on board. Then, just a couple weeks after that initial conversation between the two men, and long before Mendelson was expecting to hear much music from Guaraldi, the television man received a phone call in the middle of the night. It was his jazz piano player on the other end of the line.

Guaraldi seemed sort of electrified.

“Look, I have something I need to play for you, something I just wrote,” he told Mendelson.

Mendelson, woken from a sound sleep by the blasting phone was dubious.

“Can’t it wait until a better time, Vince?” he asked.

“No, no, no! I just wrote this! I need to play it for you right now over the phone so I don’t forget it, man.”

And so he did.

The song was Linus and Lucy.

Nothing ever came of the documentary about Schulz. As far as I can tell, the big networks weren’t that interested and the thing died in the air before it ever had a chance to land. The footage has likely leaked into the hands of people creating other projects about the Peanuts creator, I would guess. But I can’t say for sure: so I won’t.

The failure of the film, though, should not be misinterpreted. As it turns out, many of the people who had been tapped to work on it ended up sticking around to be an integral part of what was to come. And what was to some was television. A lot of it. For the big time.

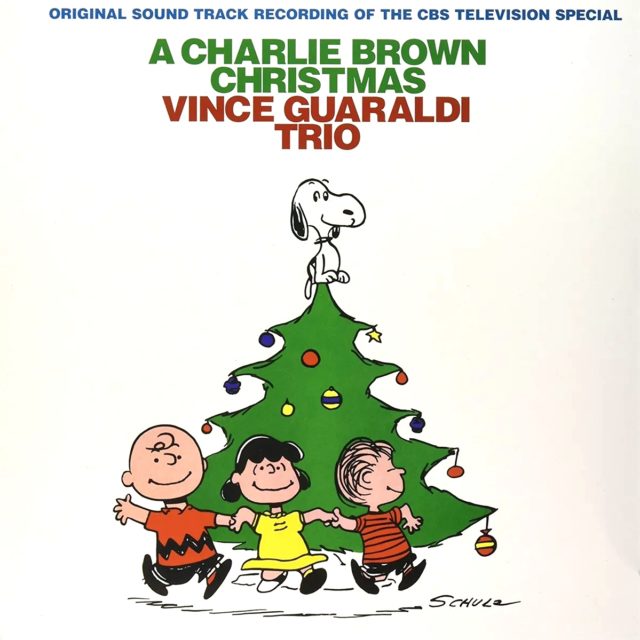

The music that Guaraldi made for the abandoned documentary? Luckily, that did ultimately find its way into the mainstream. In December of 1964, Fantasy records released their sixth Guaraldi album (but their first with a Peanuts theme) a record called Jazz Impressions of A Boy Named Charlie Brown. Featuring songs ostensibly intended to showcase individual Peanuts characters, the music quickly became bigger than any songwriter’s intentions had envisioned. Critics mostly dug it. People out in the world seemed captivated by it. There was something ethereal and melodic about Vince Guaraldi’s music.

And that something was about to prove to be a hell of a lot.

The next year, things lined up, and Mendelson, as producer, along with a former Disney animator named Bill Melendez on board as director, put together a crew and they all began working on the very first Peanuts TV special for CBS. With funding from the Coca-Cola Co., the wildly successful comic strip’s TV debut budget was meager even by 1960’s standards. Plus the entire thing was reportedly written by Peanuts mastermind Schulz in just a few weeks. From the get-go, no one seemed all that optimistic.

In house, the executives at the network thought it was destined to flop. It was too slow, they griped.

The animation isn’t up to snuff.

And the music isn’t right.

Many experienced TV veterans expected nothing less than a major Christmas time bust.

But they were wrong.

And it worked.

First aired on the night of Dec. 9, 1965, A Charlie Brown Christmas, Schulz’s weary-eyed kid homage to the ‘true spirit of Christmas’ was a brilliant display of art and emotion rarely seen by the TV-guzzling American public at that point. The only show that more Americans watched the night it debuted was Bonanza, which, with all due respect, is a show for cowboy dreamer dumb-dumbs.

For our purposes though… who cares.

I’m leaving the TV special behind now. I love it so much, but I need us to talk more about the music.

Okay?

I need this.

Because the music is nothing less than magic.

When Weiss popped that record button on that autumn day in San Fran in 1964, there was no way that either him or Guaraldi (who was in the studio to lay down a single track he’d just written for the documentary) could have known what was coming.

This is something that I like to think about.

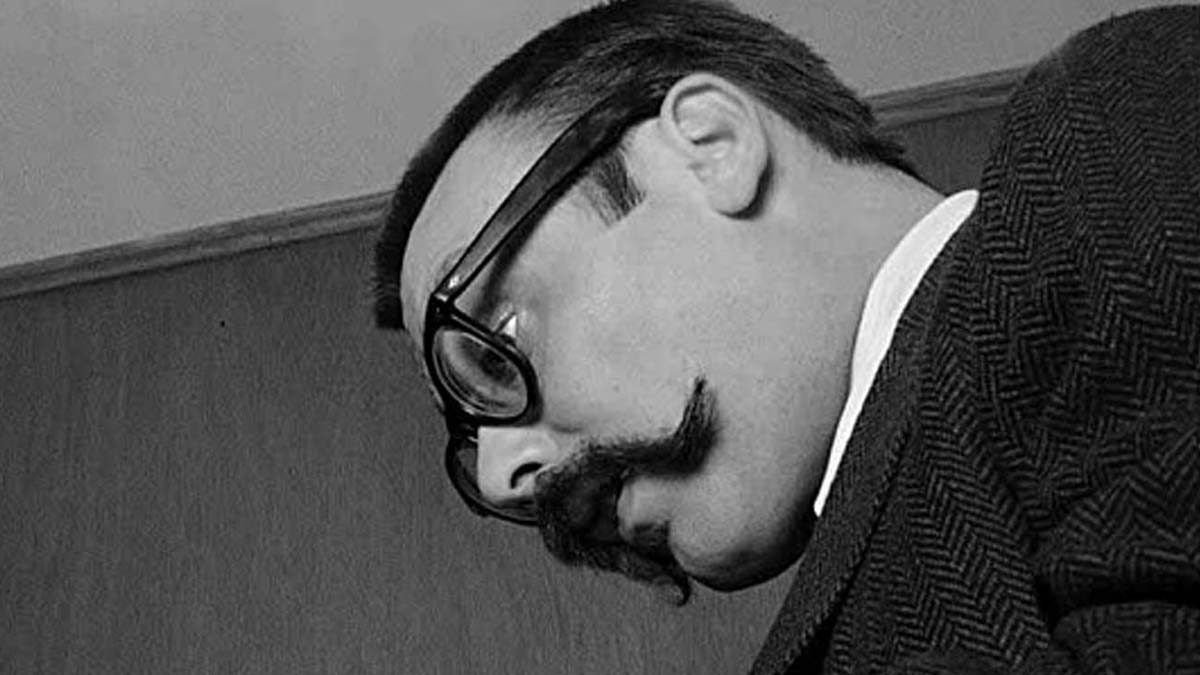

On YouTube there is a short video shot in noir-ish black and white that purportedly shows the seldom filmed jazz genius with Weiss himself. The men are side by side in the Fantasy recording studios/ each looking fairly average, like common lads of the American ’60s. It is ghostly in a way, this clip is, to see footage of men such as these two when so little footage actually exists.

But it does offer up a possible (if not probable) glimpse into the single day session not long after the footage was shot when they cut a new original of Guaraldi’s called Linus and Lucy.

It was the song that Guaraldi had woken Mendelson up to listen to on the phone.

It is a song that has come to live in rarified air reserved for cultural titans. Alongside Babe Ruth moving his giant body on spindly legs around the bases in glitchy black and white/ alongside the silence of the footage of the boys in the U-boats heading for Omaha Beach/ alongside JFK going down in the backseat of the Caddy/ alongside the first Hammond notes of Freebird/ alongside the druggy kick of the fat hitting your bloodstream with the first McDonald’s fries down your hatch/ alongside the portraits of Frederick Douglass and the poems of Emily Dickinson and Hank Williams’ wry smile and Lincoln’s marble unshot head and Martin Luther King’s deep evocative unshot voice/ alongside the things that we have selected as a people, without ever really knowing what we were even doing, Linus and Lucy is just as fitting a lead off track to the soundtrack of our collective existence as any song that has ever been written.

Everything about it is familiar to us.

We were born knowing its every weaving note.

In many ways, it is a song that — should we remove it from our systems, systematically, like with a surgeon’s scalpel and maybe a laser beam — we would just as likely feel tremendous loss when we came to. Then, not knowing what exactly has been taken from us, we would likely panic/ set upon by some kind of intense demons that feed on us sensing a thing we don’t really quite fathom.

I don’t know. Maybe that’s a bit overzealous of me to imagine things that way.

Or maybe it’s exactly what would happen if that song was erased from the little icy skating pond in our ribs where it’s been playing for a long time now.

To read the rest of this essay and more from Serge Bielanko, subscribe to his Substack feed HERE.

• • •

Serge Bielanko lives in small-town Pennsylvania with an amazing wife who’s out of his league and a passel of exceptional kids who still love him even when he’s a lot. Every week, he shares his thoughts on life, relationships, parenting, baseball, music, mental health, the Civil War and whatever else is rattling around his noggin.