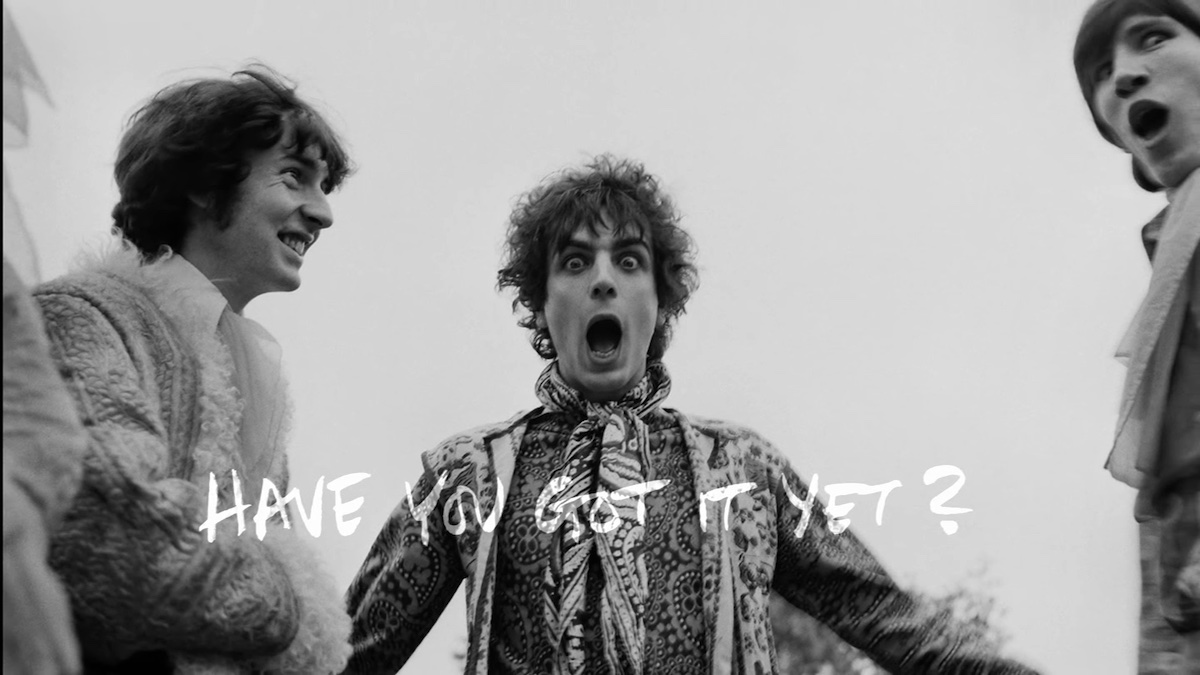

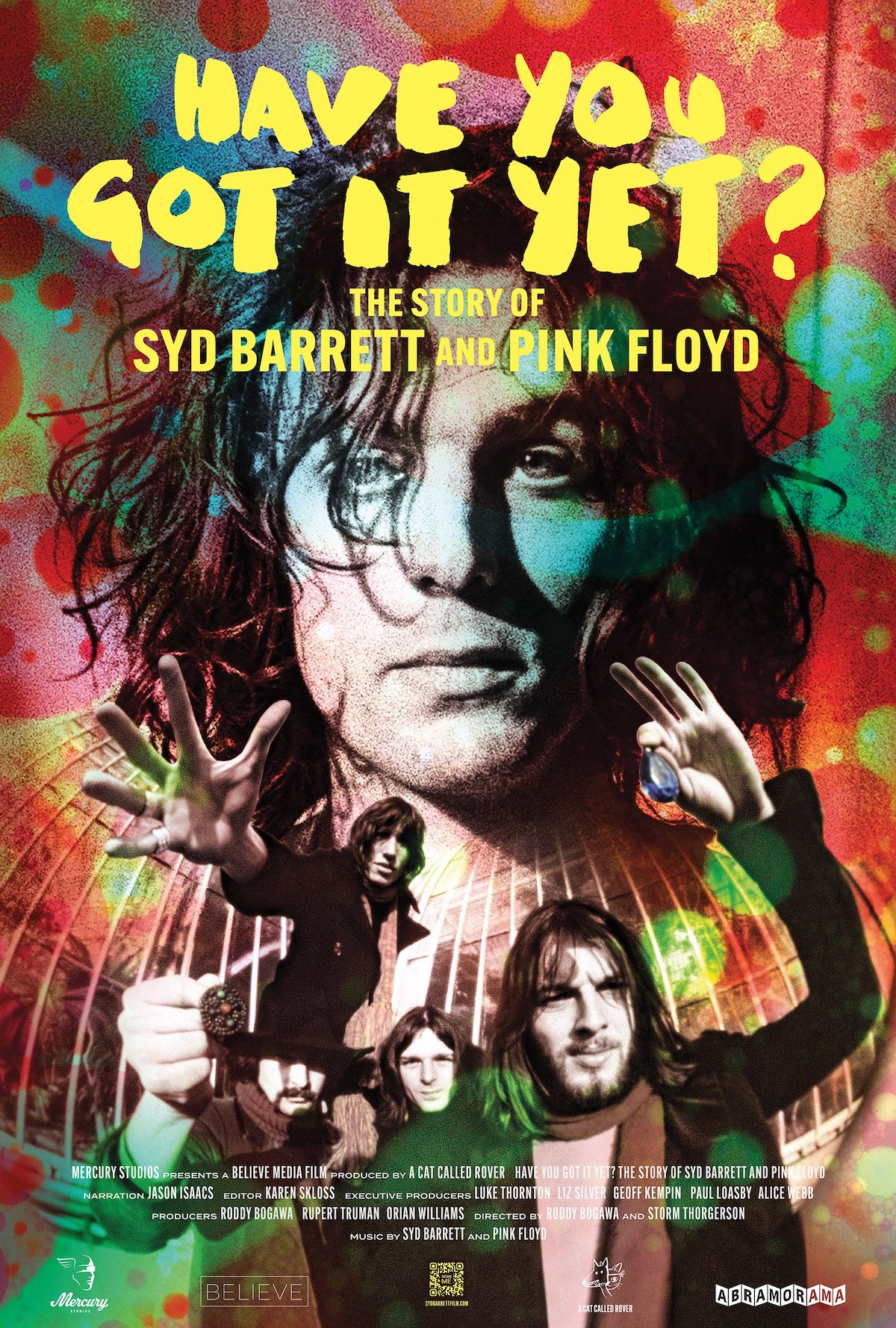

The new Syd Barrett documentary Have You Got It Yet? — a tribute to the founder of Pink Floyd — also serves as a memorial to the film’s interviewer. It’s been 10 years since legendary graphic designer Storm Thorgerson passed. The interviews in this new documentary were among his final projects. Thorgerson was a close friend of the band and most, if not all, of the individuals he quizzes from off-camera throughout the 94-minute documentary.

The new Syd Barrett documentary Have You Got It Yet? — a tribute to the founder of Pink Floyd — also serves as a memorial to the film’s interviewer. It’s been 10 years since legendary graphic designer Storm Thorgerson passed. The interviews in this new documentary were among his final projects. Thorgerson was a close friend of the band and most, if not all, of the individuals he quizzes from off-camera throughout the 94-minute documentary.

The film has the feel of a project designed to give all those involved in Barrett’s tragic unraveling the chance to never have to talk about it again.

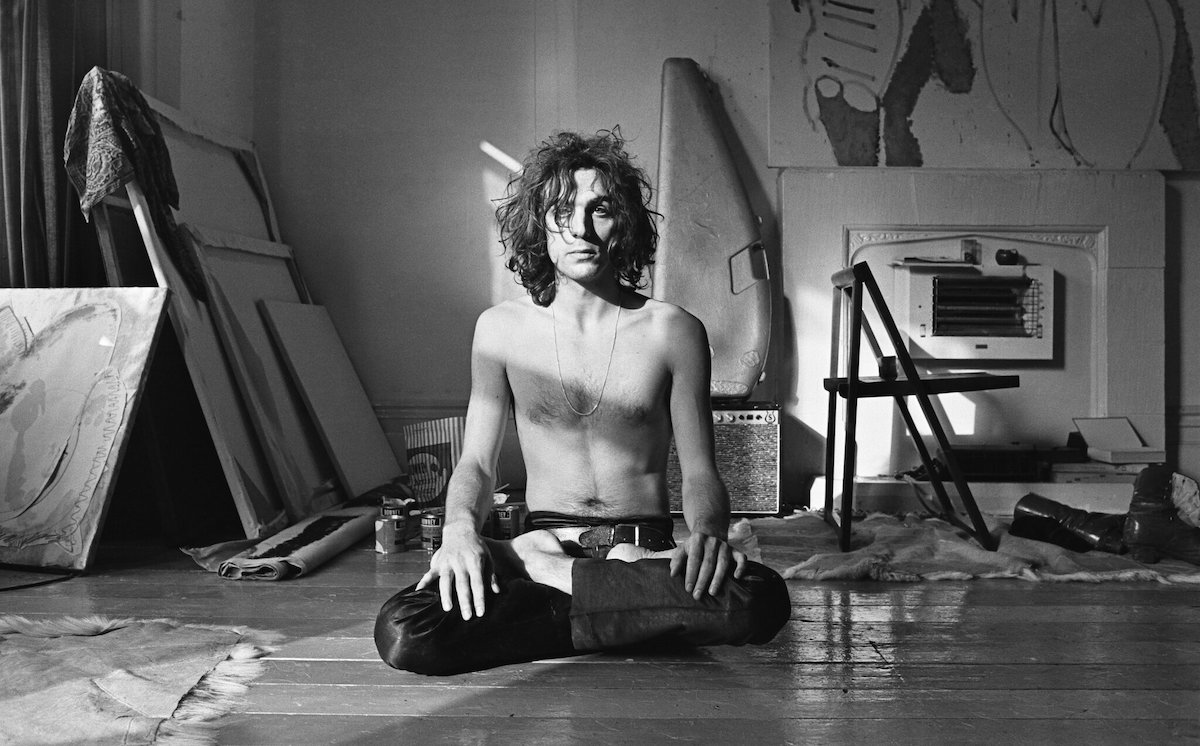

For those unaware of the story, Roger “Syd” Barrett was born in Cambridge — an intelligent and popular individual with talents for painting, music and making friends. He formed what would eventually become Pink Floyd with a bunch of architecture students. His unique, playfully experimental and very British artistry combined perfectly with musicians who were trained to design huge edifices. Think about it. The buildings we like best are the ones which are artfully designed, and the art we like best is the stuff which is thoughtfully constructed — both built to last.

Barrett was a fashionable, good-looking and likeable frontman of a young psychedelic band at the height of the swinging ’60s in London. There were lots of drugs — acid, Quaaludes, Mandrax, weed, opium, heroin — and the band was associated in a major way with a post-war scene which celebrated escapism and experimentation, and used drugs to achieve this. Every time Barrett turned around, someone was pushing LSD on him. Not that he had any hesitations about taking it. The drug, combined with fame and an underlying mental illness, quickly began to transform the effervescent counterculture idol into a dead-eyed, unpredictable and uncooperative pain in the ass. His ability to harness his talent and create unique pop music started to slip away.

Eventually the band literally moved on without him, and after making two challenging, fragile solo albums, the penniless Barrett walked to his childhood home Cambridge from London and never re-emerged publicly again. He died of cancer in July 2006.

I’ve seen and read pretty much everything there is to see about Barrett, having become a major fan when I was around 16. I went to see this new, supposedly definitive film, hoping to see, hear and learn something new. I didn’t really. It’s pretty safe and lovingly done. Setting it apart from the low-budget Barrett and Floyd docs you might find online is the fact that this contains no canned music. The soundtrack is all original, actual material — in some cases outtakes I had never heard before. One of my favourite Barrett songs is It Is Obvious from his second solo album (1970’s Barrett). The doc used part of an outtake of it, hopefully not as a way of accentuating Syd’s shambolic state. In fact, the film used several of his more-challenging, raw tracks like Birdy Hop and Word Song (both from the 1987 outtakes compilation Opel), when I would have preferred his stronger, more together material.

There is new stuff to see in this film. Loads of it. There are several fantasy sequences, which work like dramatised scenes — actors portraying Barrett at different ages, but doing symbolic activities like diving into a pool or walking across a meadow to a standalone door. The interviews with Floyd members Roger Waters, David Gilmour and Nick Mason were done specifically by Thorgerson for the film as well as the numerous others involving Barrett’s sister, several former girlfriends, managers, roommates and school friends.

Where the documentary let me down was in two areas. The first of which is what I’d call continuity and illustration. There are several stages of the movie where the dialogue involves an entirely different album than the one being shown, or a different era than the one being discussed. There are times when follow-up questions or follow-through audio/video is required but not completed. For example, Floyd’s 1967 tour to the U.S. with The Jimi Hendrix Experience is routinely described as having been a disastrous fiasco due to Barrett’s increasingly erratic behaviour. In the documentary they counter this tale with an anecdote that many of the shows were recorded and the tapes tell a different story — that the band often sounded great.

But we don’t get to hear any of that. I would love to hear some live Syd Barrett-led Floyd. It’s incredibly rare. There are some recordings on Floyd’s Early Years box set, but of a Stockholm show in 1967 where Barrett’s mic either wasn’t on, or he was nowhere near it. Otherwise, the band did indeed sound fantastic — powerful and reasonably rehearsed.

The filmmakers should have found a way to get some of that U.S. tour audio. They also should have had a mental-health specialist involved in the making of the movie. Those interviewed mostly all share theories about what happened to Barrett and why — but they’re not professionals. It’s a safe bet Barrett’s ordeal would have been quite different if it happened these days. His sister talks about how difficult it was to care for him, but we never really hear details of that. Was he ever diagnosed?

The band members talk about their regrets — first with how their leader and friend was abruptly dismissed. They simply decided not to pick him up en route to a gig on Jan. 26, 1968. He never quit. There’s never any discussion about the legality of what was done and how it was handled. When the two Pink Floyd albums containing Barrett’s songs were re-released as a two-record set called A Nice Pair in 1973 to capitalize on the popularity of Dark Side Of The Moon, the version of Syd’s incredible Astronomy Domine was replaced with the live version by the Barrett-less Floyd on Ummagumma. The band stopped playing the song live in 1971 until their 1994 tour. It is one of only a handful of Barrett-penned songs they played after he left the band. The others are Matilda Mother (until Oct. 16, 1968), Flaming (until Nov. 27, 1968) and Pow R. Toc H (until Nov. 1, 1969). After Barrett was left behind, the band only played his biggest hit — See Emily Play — two more times. Ever. By comparison, they played the boring Set The Controls For The Heart of the Sun nearly 300 times.

Sadly, the real reason we don’t know more about what happened to Barrett is because he became so reclusive. He withdrew from public life entirely — occasionally being tracked down by fans or tabloid journalists hoping to get some great photos and insight from the Madcap himself.

The bottom line. This doc is well-done. It is a loving tribute to someone they all knew, loved and respected. They just were too young to know how to deal with it properly. As former manager Andrew King points out poignantly and emotionally in the film, it’s a sad story. One which probably would have been no matter what anyone did. It could, in fact, have been much worse.

Legend, martyr.

• • •

Area Resident is an Ottawa-based journalist, recording artist, music collector and re-seller. Hear (and buy) his music on Bandcamp, email him HERE, follow him on Instagram and check him out on Discogs.