“A prison taint was on everything there. The imprisoned air, the imprisoned light, the imprisoned damps, the imprisoned men, were all deteriorated by confinement.” — Charles Dickens, Little Dorrit

Sitting there in his rattling irons, on a winter train headed straight away from everything he had ever known, the world was sliding by, freedom slipping away with every passing mile. Farms like the ones he’d wandered by and worked on all his young life so far, they came up into his vision for just a moment or two before they slid behind the barreling train, into the void of the world he could no longer enter. Patches of dead weeds standing tall at the corners of old bank barns, he would have ignored them to no end not long ago. But now they seemed angelic and beautiful and he craved to just hop off this damn train right now, even as it moved along at a good clip, just to tumble down into these foreign fields and pick himself up and go to sit there in the random nature, in a stranger’s weeds, as a show of remorse. As a signal that he was sorry for the crime. Or for getting caught, at least.

Sitting there in his rattling irons, on a winter train headed straight away from everything he had ever known, the world was sliding by, freedom slipping away with every passing mile. Farms like the ones he’d wandered by and worked on all his young life so far, they came up into his vision for just a moment or two before they slid behind the barreling train, into the void of the world he could no longer enter. Patches of dead weeds standing tall at the corners of old bank barns, he would have ignored them to no end not long ago. But now they seemed angelic and beautiful and he craved to just hop off this damn train right now, even as it moved along at a good clip, just to tumble down into these foreign fields and pick himself up and go to sit there in the random nature, in a stranger’s weeds, as a show of remorse. As a signal that he was sorry for the crime. Or for getting caught, at least.

Kids throwing snowballs at the passing train, he’d see them through the dirty glass of the windows, out there laughing in the slate afternoon. Their arms bent down to their knees, frozen in position as their powdery artillery shells moved from their free mittens through the free air towards the free train itself/ some slashing/ some arcing/ some seemingly stopped in the sky for an instant or two before it began its descent back down towards the free land and the free train and the unfree people in it’s path. Prisoners, onetwotreefourfive, in the window seats near the guards with the rifles, they would have watched as the free snowballs hit that free glass with soft force/ a kind of thud-thud-thudthud-thud/ like the canons in the war of the years to come would sound to him. Someday.

County after county, town after town, river after stream and stream after river, a train moves a man from somewhere to somewhere else and depending on the timbre of the journey, on the reason for traveling, it can be either an uplifting journey primed by the excitement of a coming unknown/ or it can be a dreadful, horrifying thing/ moving you ever closer to a dead body of a loved one/ or the words of an unexpected goodbye/ or, as in our case here, closer/ ever closer/ to an impenetrable fortress of punishment. To a kind of un-freeing that has always been, up until now, simply unimaginable.

Miles from his country home then, as the afternoon sun began to sink into the lazy gauze of a dying day, the looming skyline of Philadelphia must have appeared like a fantastical kingdom in the eyes of the 21-year-old Deviney.

It was early January, 1859, and the city was surely ashen and smoky and unwelcoming. After all, everything that awaited my wife’s great 3x grandfather that day was steeped in mystery and fear and shrouded in regret.

The lad, as it goes, was headed to prison. Far, far from home: in a city the likes of which he had never even tried to imagine, let alone laid eyes upon. Mid-winter January afternoons on the eastern seaboard historically has me betting that the old town was frigid and dank that day he arrived. True, true, there are no guarantees, of course. Unable to find any official weather reports for that exact period, I’m basing a lot on nothin’ at all/ leaning hard into speculation based on what hardly registers as true history anymore: my own personal experience.

Still, I’m not totally without merit here. I mean, I have known some January days in that city in my time. More than a few, quite frankly. Most of them have been wickedly cruel, with little rest from slamming train-like winds into the faces of the people who turn certain corners onto certain avenues when certain gusts are being born out by the Delaware River in order to invade and maraud with no quarter upon every cursing hunched-over street walker it can find.

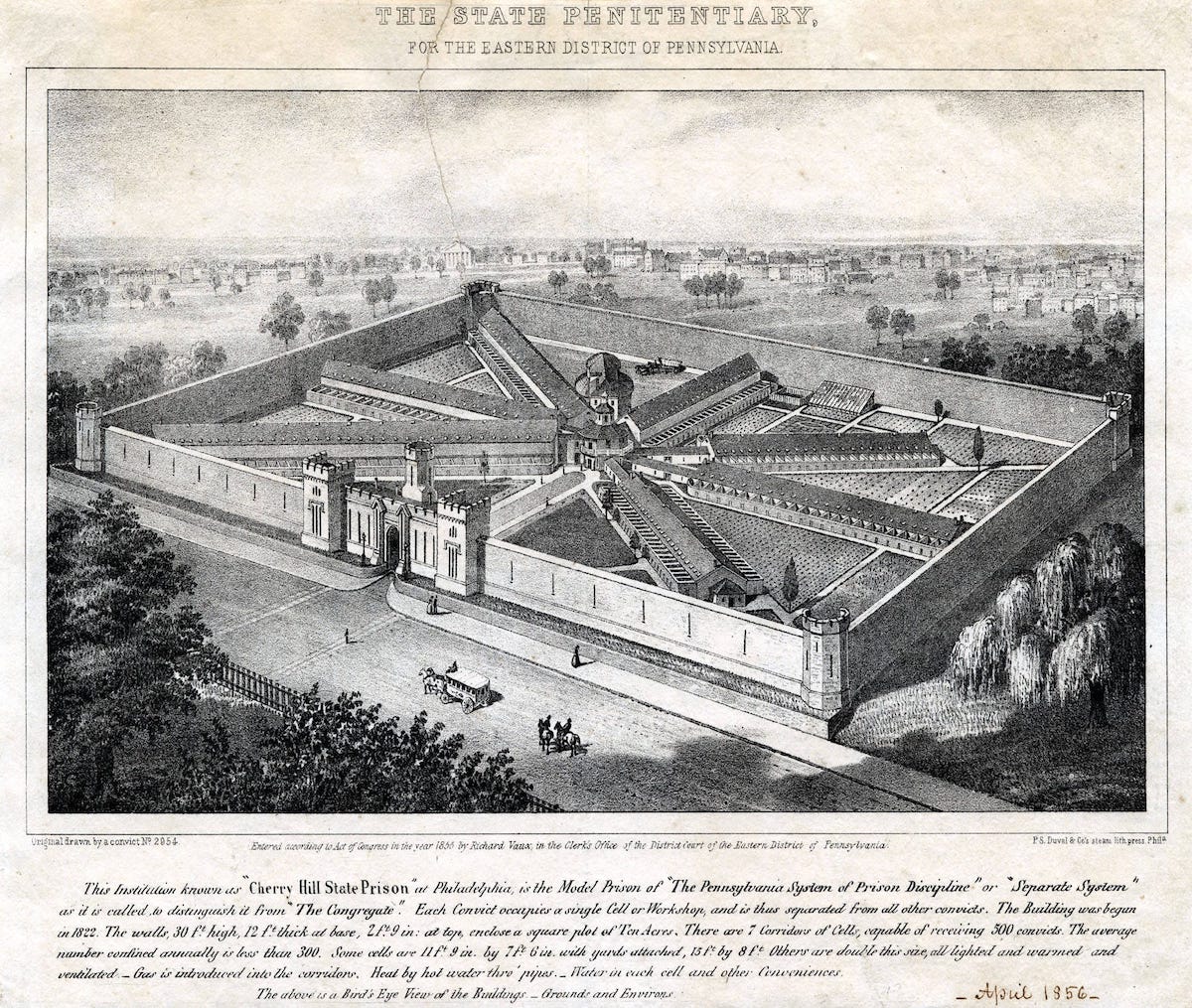

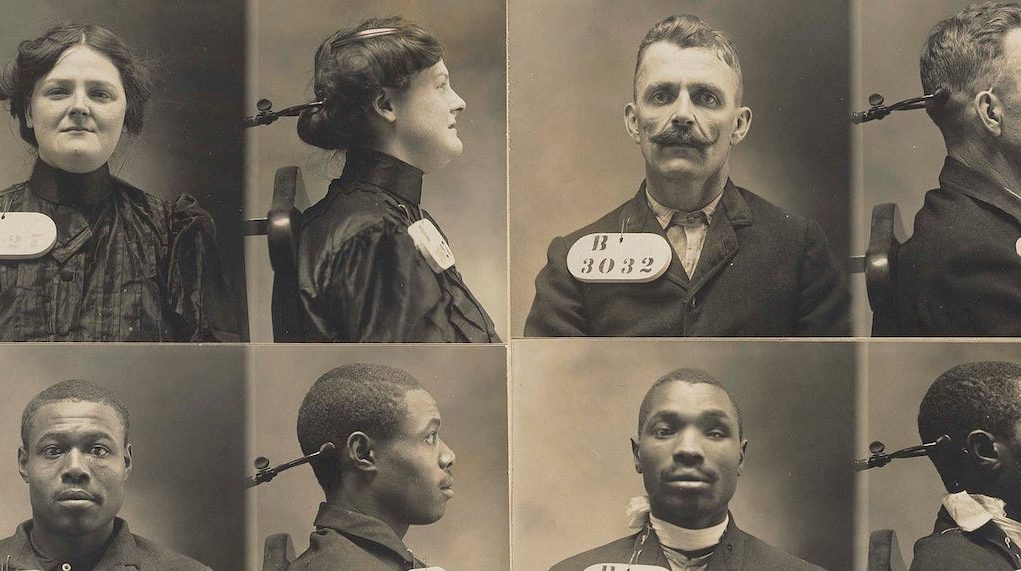

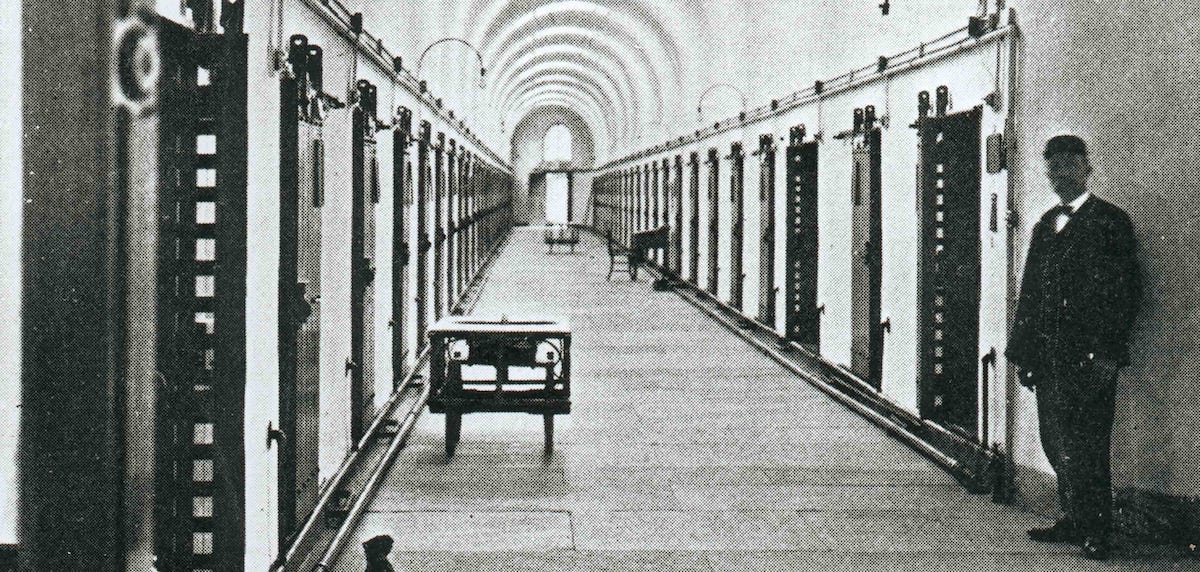

And so it goes that, here, in my imagined history of a true history, I make it cold as hell for the country boy the first moments he steps off the train. In shackles, perhaps/ in cuffs for certain. He’d been tried and convicted of larceny not long before. And true to the manner of a freshly rested court, I suppose, his post-holiday sentencing, in the days just after Christmas and New Years, had found him sentenced in Perry County on the 5th of January and quickly shipped off to Philadelphia. To Eastern State Penitentiary. A stranger in a strange land if there ever was one.

He must have been scared as hell.

And he must have been doing everything in his power to hide that fact from everyone.

“Opportunity makes a thief.” — Francis Bacon

Once, on a street in London, where the theaters draw thousands of tourists from all over the world/ bus loads/ train loads/ buckets from the sky tipping over and out rushes a rambling wave of humanity/ people with money/ people with no idea where they are except for the thrill of realizing- from a height above themselves on those bustling busy streets- that they are in London/ grand old London/ once, I was walking with a young lady/ sifting though the throngs/ trying not to lose my companion in the jam of the incessant ocean of faces and voices and shoulders touching/ arms rubbing/ when I felt my wallet go.

It had been in my back right pants pocket but then it wasn’t anymore and somehow I understood that in the moment it was happening. This isn’t often the case, I know, when an American like myself is drifting unmoored through the London theatre district masses. We, as a rule, never realize until later/ when we go to pay for a few pints in a pub or for a chintzy dish with the Queen’s face on it or for a taxi at the end of a night/ that our wallets are, quite rudely, missing.

Yet on this particular afternoon, I beat the system and felt it go and swiftly I sprung into action. But what happens in odd strange moments like these is that time slows down and you begin to wonder what you are about to run into on the distinct other side of this spinning around you have committed yourself to, unconsciously, I’d say. It’s all reaction, these things, you know? There is very little courage or cunning or intelligence at play at all, I would say.

Hell, halfway back into my wild move to confront a pickpocket, I also began to envision, quite clearly and with much intense detail, the slender silvery blade of such a small but useful knife, as it reflected the excitement of these lanes with local neon sparking off it’s surface/ like a masterful painting that captures the allure and the danger of big city movement/ in the very instants before that same blade thrusts slowly and deliberately into my belly/ like a pin into a potato/ like a finger into a pudding/ and sliced me wide open so that my guts/ my heaving grey bucket of goosenecks in their juices all slipped out of my shirt and onto the sidewalk into a heap rising up from a puddle where a thousand people would quietly cease their momentum to stand in fascinated awe: watching me die on an autumn afternoon as The Producers crowd was being let out/ heading to their early dinners/ chit-chatting and thirsty and ready for some wine.

Who can blame them? Any of them? Not me. No way.

And yet, upon reaching my destination, I observed no knife and no criminal and nothing I had been expecting. But rather, in the place of what I thought I would find there stood a very frail looking creature of which, even to this day, I am uncertain about as far as the sex goes. They may have been a boy, or they may have been a girl. They may have even been a man or a woman, but in that case they would have been quite unusual as far as that goes. Either way, I had them by the arm now and they were squealing/ begging me to let them go/ and no one else was clocking any of this as I slammed the thief up against the painted door of a closed shop and began to feel how much stronger I was than them and how extremely unexpected any of this was to me.

My wallet reappeared and I felt satisfaction, warm like whiskey or wide awake pissing your pants. I had my hand on his/her throat and I was glaring deeply into their eyes and their voice was high-pitched and I could tell they were scared, just like I was scared/ our lives intersecting on this insanely busy road at an insanely busy time of the day/ and I remember thinking how much it would have been a disaster for me if my wallet had gone missing and how much I felt like I was dreaming with my wallet in one hand and my thief in the other as I searched my mind for the punishment/ for the sentence/ for the thing that had to happen at this juncture which I hadn’t asked for or deserved whatsoever.

Then I recall, with great clarity, the release. Much as you might release a magnificent trout, so wild and free, and yet so threatened by the overwhelming sense of imminent death/ the toxic inebriation/ the fuzzy vision and the slamming heart that should and does come with being certain that you are about to die at the hands of another/ I released my grip and the thief’s eyes they lit up/ and my hearing came roaring back from the muffled tunnels it had gone down in.

I heard the streets again as I watched my thief take one step, then two steps, then a third step back the way we had both just come, before disappearing into the river of people, never to be seen by me again.

The thief. In their eyes I saw a person I have never forgotten. A weak bodied urchin grappling to survive. I doubt David Deviney was the same kind of thief. I doubt he was cut from the same kind of cloth that my own Londonish Charles Dickens-y downtrodden punk’s life had been. But also, I don’t know.

There are so many things that we never know about the people that try to take shit away from us so that it can be theirs. We all want to blame it on liquor or drugs or shiftlessness, but I’m not so sure.

Being a thief is an old, old way of living.

Being a thief, stealing out in the country or down in the city, it’s an ancient style of rolling through your days. Of surviving. And it isn’t easy. But some people are good at it. And they say you should do what you love too, you know?

Anyways.

I don’t like straight-up thieves.

But I don’t not like them anymore either.

To read the rest of this essay and more from Serge Bielanko, subscribe to his Substack feed HERE.

• • •

Serge Bielanko lives in small-town Pennsylvania with an amazing wife who’s out of his league and a passel of exceptional kids who still love him even when he’s a lot. Every week, he shares his thoughts on life, relationships, parenting, baseball, music, mental health, the Civil War and whatever else is rattling around his noggin. Once in a blue Muskie Moon, he backs away from the computer, straps on a guitar and plays some rock ’n’ roll with his brother Dave and their bandmates in Marah.