THE EDITED PRESS RELEASE: “I had this idea that — I’m not a religious person, but I do believe that there’s a spirituality to a lot of people and they’re not religious,” says Lambchop’s Kurt Wagner. “You don’t have to be religious to be a spiritual person, right? You just don’t have to. There should be an acceptance, or a way of recognizing spirituality without it being overtly religious.”

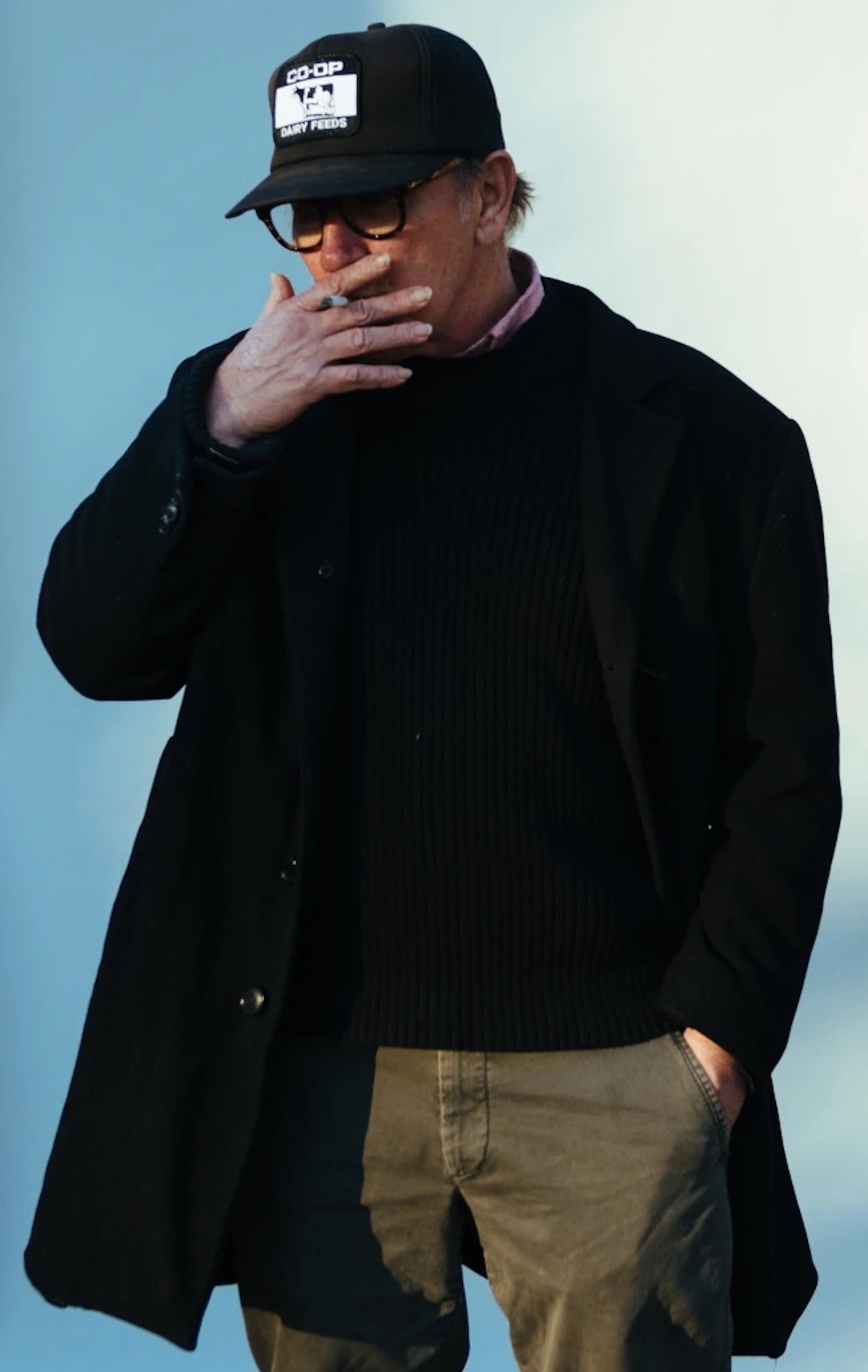

The only prophets worth a shit are the reluctant ones, and so it was that right before he started working on what would become his new album The Bible, Wagner found himself at the proverbial crossroads. Nearing the end of Lambchop’s third decade as a recording artist, Wagner felt musically isolated. He questioned whether continuing to make music even made sense. “I feel weird because I’m going to be 64, dude,” he says on the phone between drags of a cigarette. “What the fuck am I doing?” The Bible is the sound of Kurt Wagner asking big questions like that one — and all the other ones.

Wagner has always considered himself to be a late bloomer — he was 35 when he started Lambchop all those years ago, way back in the first big funk of his life. After losing his girlfriend and his job in a brutal Chicago two-fer, he came home to Nashville and started hanging around a songwriters’ night called The Working Stiff Jamboree at the Springwater Supper Club. He would bring the afterparty home to his house. “I finally started writing songs because nobody else was,” he says. “And we needed something to play other than covers.” This was Nashville, after all, home of the country music machine — there were legions of musicians showing up here every day just to play somebody else’s songs. But Wagner’s distaste for the cover song wasn’t only due to some noble artistic integrity. “I was that bad a musician,” he laughs, a little ruefully. “I literally would only play the chords I knew in the song and skip the ones that I didn’t.”

So he would invent rules to gamify the sessions, to get this demimonde of wannabe Nashville musicians moving in a different direction. “I remember I would try to handicap them somehow,” he says. “If they were a really great guitar player, well, no, you’ve got to play the organ.” Then he would sit back and watch and listen. He found his writing voice in this observational style. “It was like journalism, in a way — just reflecting and commenting on my life, my friends’ lives, whatever.” Wagner would change some details and obscure others to disconnect his insights from the individual, to more closely approach the universal. His lyrics and his phrasing conveyed a profundity that he didn’t know he was capable of — he had found his singing voice through finding the words to sing.

He’s terminally modest, so you believe that’s what he actually feels when he says his true talent was convincing enough burnout Nashville freaks to come over to his crib long enough to create the unhinged outsider country sound that fueled those first few Lambchop records. “We represented, in my mind, the actual Nashville sound,” he says. “These are people who were born or raised here, and this is the music that’s actually coming out of Nashville.” He was seeing how far he could push this self-definition when he facetiously called it country music in his band bio. “Careful what you call yourself,” he cautions, “because people don’t actually listen to music. They’ll just read a couple lines of your bio, and the next thing you know, you’re the most fucked-up country band in Nashville.”

So if that’s the power of the bio, what will they believe when Wagner tells them about The Bible, about this album that was recorded in the middle of a plague, when he was isolated from his Nashville community yet closer to his own nuclear family than he had been in a long time? It was during this time of renewed musical self-doubt that he was serving as the primary caretaker for his own father, watching his dad get COVID and then recover, and then have a stroke and recover, and then get both of his hips replaced and recover. Is this the album where Wagner confronts his own mortality because he was thinking about his dad so much? Or is this his Minneapolis album? Wait, what?

During that first year of quarantine, Wagner was up worrying in the middle of the night when he tuned into his friend from Minneapolis, Andrew Broder, playing piano on Instagram Live. A couple years prior, Wagner had met Broder and a whole gang of Minneapolis musicians in a Berlin studio, through their mutual friend Justin Vernon. He was deeply intrigued with the entire scene these guys had going up there, maybe because the spirit of it reminded him of his original weirdo music scene in Nashville, and now he was entranced watching Broder play piano in the middle of the night online. So he called him up. “Dude, I’ll get you in a studio,” he says. “You just go in there for like three or four hours and do your thing.” Broder did just that and sent him back a dozen 20-minute-long pieces. And so it was that Wagner found himself in Minneapolis in the sweltering summer of 2021, in a decommissioned paint factory-turned-practice space, when everybody was still kind of looking at everybody else as a potential source of disease. He had entrusted himself to this piano player and his mad genius of a production partner, Ryan Olson.

“Ryan and Andrew, they’re like two sides of my personality,” Wagner says. “And if you put them together as a team, they represent me.” This would be the first time Wagner let somebody else — not to mention somebody else without any sort of a connection to holy, old Nashville — produce a Lambchop record. “Yeah, and that’s joy. I feel that in what I’ve been doing all this time. It’s all about really not getting too fucking hung up being a serious fucking musician, and enjoying each other’s company. It’s a social thing that we do together. And it should be enjoyable. If it’s not — which I think it ends up being for most musicians as they spend their careers doing it — it becomes a fairly joyless fucking thing. And when I see that coming, I do not want it in my life. That’s just like, why do it if you’re not enjoying it?”

It was in that decommissioned paint factory in Minneapolis, watching a bunch of burnout freaks play their instruments, that Wagner found his way to writing The Bible. The sessions reminded him of those long-ago days at the Springwater Supper Club, when he first brought the afterparty back to his house. But maybe because he wasn’t the one making the afterparty rules this time, the music on The Bible is more unpredictable than it’s ever been on a Lambchop record. Jazz careening into country, into disco, into funk, and back to country. And he knows that he can call it whatever he wants to call it in this bio. And he trusts his own voice — that he can tie all those sounds and styles together with his own words and phrasing. Whether the lyrics are observing the dire headlines of racial strife from that summer in Minneapolis, or just the graffiti outside that paint factory, or the bumper stickers out on the highway, or his own feelings about his father confronting his mortality back home, or about him doing the same on his own wherever he may be in the world. This is Lambchop’s new album — born in a new place but out of a process that he first discovered back home in Nashville, the one that helped him find his own voice in the first place. Amen. This is The Bible.”