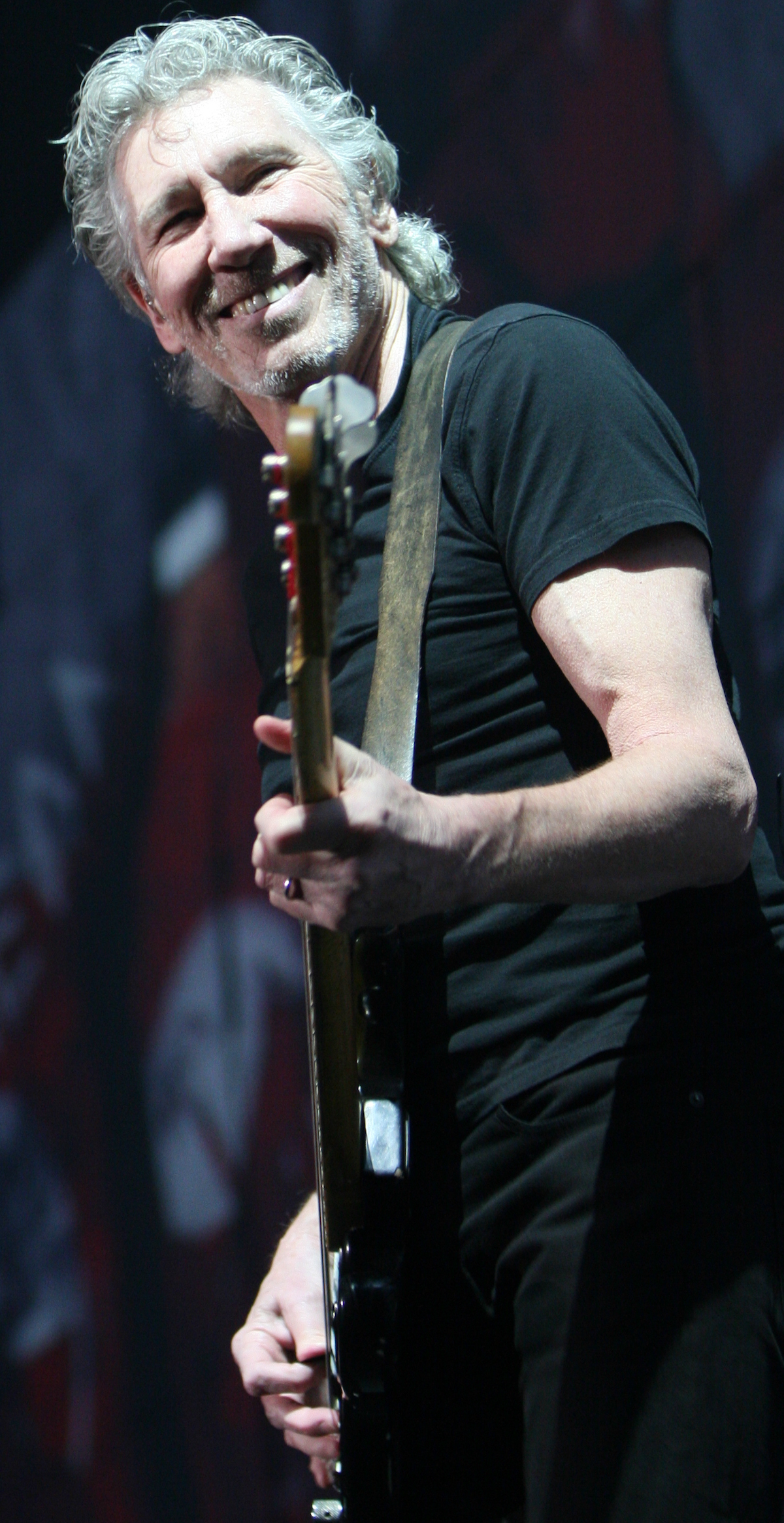

Roger Waters speaks his mind. For better or worse.

That’s obvious to anyone who’s read, watched or heard an interview with the opinionated, mercurial singer-songwriter and former Pink Floyd member. When faced with a question or opinion he doesn’t appreciate, he’s been known to lose his cool, hurl insults and terminate interviews. So I’d be lying if I said I wasn’t a tad nervous about speaking to him in 2015 over his latest movie version of The Wall. But as is often the case, I found him to be friendly and thoughtful — the opposite of his prickly reputation. Maybe it was because I avoided talking politics or Pink Floyd. Or maybe I just caught him on a good day. Either way, I breathed a sigh of relief when it was over. And I later heard from a publicist that Waters made a point of saying how much he enjoyed talking to me, which I thought was kind of him. Anyway, since Sept. 6 is his birthday, it seemed like a good day to pull this one out of the archives. Enjoy. And if you see Roger, tell him I’m still waiting for my sweetie.

Roger Waters has made the final cut.

To the former Pink Floyd singer-bassist, his latest cinematic incarnation of The Wall represents closure. For himself and the audience. “It’s the final piece of the Roger Waters jigsaw puzzle,” the 72-year-old artist claims. “You’ve got it. That’s all there is. I can’t open myself up any more than I have.”

He is not exaggerating. Although first and foremost a concert movie anchored by a stadium performance on his 2010-2013 Wall tour, the 130-minute film — tellingly titled Roger Waters The Wall — also documents an emotional journey by the veteran musician. Personalizing the updated musical’s themes of war, death and fatherhood, Waters travels through Europe by car, reconnecting with the ghosts of his past. He takes his family to the grave of his grandfather, who died in France during the First World War. He visits a memorial to his father, who went MIA in Italy during the Second World War when Waters was just a baby. And, in the film’s most moving shot, Waters sits in his Bentley on a French roadside, weeping as he reads the letter his mother received all those years ago, informing her that her husband has been lost in battle. Set between the dynamic and spectacular performance footage, these scenes elevate this version of The Wall far above and beyond the typical concert movie. On Remembrance Day, Waters called from London up to discuss the film, his first rock album in more than 20 years, and why there might still be another brick in The Wall saga.

Congratulations. I think The Wall is the first concert film that made me cry.

Thank you. I mean that sincerely. I’m happy to say it moves lots of people to tears. That is hugely gratifying, as you can imagine.

Obviously, you could have gone with just a straight concert movie. Why was it important for you to include the road-trip footage?

Nobody’s asked me this, so I’m glad you have. It’s all part of my personal journey; the tearing down of my own walls. I was a deeply embarrassed little kid who had real trouble exposing my emotions. Then I went through that whole process of rock ’n’ roll and found that very difficult as well; I found it almost impossible to perform to small audiences, so I hid behind all the noise. And now my journey has taken me to someplace where … you know, I just realized something. In the song The Final Cut, I sing about wanting to show my naked feelings, to tear the curtain down. It goes, ‘I held the blade with trembling hands prepared to make it, but just then the phone rang; I never had the nerve to make the final cut.’ See, I can even remember some of my own lyrics! But anyway, for me, putting the road footage in is me making the final cut. It’s tearing the curtain down.

Doing that scene in the car with the letter must have been incredibly difficult.

Yeah. I’d read that letter once before in my life and I gave it to (director) Sean Evans and said, ‘Here, you keep this. I’m not going to look at it again until we’re somewhere in France. And when I look at it, you better bloody well have film in the camera, because I’m not doing it twice.’ But the other reason I put that footage in there is because of doing the tour and meeting those vets. There’s a bit in the film where I talk about the one who says, ‘Your father would be proud of you,’ which opened me up like a fucking melon. I couldn’t handle it at all. But there were a lot of moments like that. It just sort of destroys you. I felt it was important to show that.

Did this whole process give you any closure on a personal level?

Well, what isn’t in the film is that after we shot for the day in the memorial garden in Casino, Italian television was there and I did a 30-second, ‘Thank you, it’s been lovely’ thing. And some old soldier who lives on the east coast of Italy, his name is Harry Schindler, saw this and decided that he was going to make it his personal business to find out where my father had actually died. And he did, by doing research and going through regimental records. And then he went to the local town and he persuaded the local counsel to erect a monument to my father in the playground of the local elementary school. I went with him there to unveil it on the 70th anniversary of my father’s death. And if you wanna talk about moving, you should have been there that day. I put on a suit and the whole town was there practically, and it was absolutely amazing. Harry, of course, has since become a very close friend of mind. He’s 94 years old. He was actually fighting about a mile away from my father on the day my father was killed. Anyway, he was trying to figure out what he was going to write on the monument. My father’s name obviously goes at the top, but he thought it should also say, “In memory of Second Lieutenant Eric Fletcher Waters and all the other Allied missing.’ And I said, ‘Hang on, Harry. You can’t use the word Allied. It’s not just about the Allied missing, it’s about all the missing. This isn’t just about our lot. I know the other missing were the Germans. But they weren’t Hitler. They were just blokes who’d been told to join the bloody army and get on with it.’ So we put a quote from one of my songs at the end of it. It’s from Final Cut. it says, ‘Ashes and diamonds, foe and friend / We were all equal in the end.’ That is written on an obelisk in a school playground in the middle of Italy. And that moves me almost more than anything else.

Over the years, you’ve reinterpreted and recontextualized The Wall several times. Do you think you could do the same thing to other works in your past, or is The Wall unique?

I have no doubt there are other works. The ones that spring to mind immediately are The Final Cut and Amused to Death. I’m sure they would bear a similar treatment. But I’m happy to say that I’ve also got a bunch of new ideas. I’ve got a lot of new songs. I’m in the middle of making a new album. And I am full of enthusiasm to make an arena show out of the new album and old songs that can work together. I did that once before with a thing called Radio KAOS where I used a new record and threw a bunch of old songs in as well. I think I know better how to do that now. And it would be a perfectly legitimate thing to do. Because one thing I do know about rock ’n’ roll audiences is that they’re a lot happier if there are some oldies in the set, and not just a bunch of stuff that’s completely new.

Does the amount of time that’s passed since you released a new album add any urgency and pressure, or are you immune to that by this point?

I am fairly immune to it. The truth is, you have to notice something before you can paint it. So part of my job is to notice things that are going on. And sometimes it takes me a long time to mull my way through them, or to write enough material, or even to think that there’s something coherent or cohesive enough to be bothered. You know, you start putting the first marks on a sheet of clean paper and before you know it, you’re in the middle of a painting that could take a long time to finish.

Is it perfectionism that makes you work so slowly?

Perfectionism is big part of it, yeah. I care about the meanings of the words I use. That may sound very prissy and pretentious, but I do. And I’m content to be that way. This new record I’m making will be more of the same. It’s very unlikely that I’m going to suddenly stop making the kind of work I’ve made for the last 50 years and start doing something different. So the new work will be similarly confrontational and anti-war and all the rest of it. As all the work has been over the years. I make no apologies for that.

Is there anything left on your bucket list?

Well, I’ve been working with some people on a theatre version of The Wall. We’ve done some workshops, and having reduced people to tears with just eight actors and a piano, you think, ‘Wow, that’s really spine-tingling.’ So I think we’ll do that. I hopefully will eventually publish my book. And apart from that, I don’t know.

What do I win for getting through an entire interview without mentioning the name of your old band or asking about a reunion?

Ha! I’ll send you a sweetie! Well done!

• • •

A brick-by-brick history of The Wall

THE ORIGINAL ALBUM

Pink Floyd’s 11th release — and arguably the band’s crowning glory — was ironically inspired by one of the lowest moments on their 1977 tour. During a show in Montreal’s Olympic Stadium, singer-bassist Roger Waters was so irritated by a rowdy fan that he spat on him. After, the show, he discussed his feelings of alienation with producer Bob Ezrin, saying he wanted to build a wall onstage between the band and the crowd. Starting from there and drawing upon his own life and that of doomed former bandmate Syd Barrett, he crafted the classic concept album about a young man named Pink who loses his father in the war, is abused by tyrannical teachers, and becomes a depressed rock star who isolates himself from the world and his family with drugs. Released in 1979, it has gone on to sell a reported 23 million copies and become one of the most acclaimed and enduring albums in rock.

THE ORIGINAL TOUR

Staged in just four cities — Los Angeles, New York, London and Dortmund, Germany — the original production was a landmark in live concert production, introducing many of the elements that it continues to feature to this day. Due to its complexity, it was staged just 31 times, and reportedly cost more than $1 million before the first performance. During the tour, the bandmembers reportedly travelled in separate mobile homes which were parked in a circle with the doors facing outward. Perhaps not coincidentally, it was also Pink Floyd’s final tour with the classic lineup of Waters, guitarist David Gilmour, drummer Nick Mason and keyboardist Richard Wright.

THE FILM

With its strong narrative and lead character, The Wall seemed tailor-made for the silver screen. So, in 1982, director Alan Parker — working from a screenplay by Waters — filmed a fairly faithful version of the tale, with Bob Geldof playing Pink and animator Gerald Scarfe supplying iconic sequences like the marching hammers. The soundtrack featured reworked songs and some new material. Although Waters has called it “a very unnerving and unpleasant experience,” the film eventually earned $22 million, garnered generally positive review and won two BAFTA awards for best sound and best original song.

THE LIVE ALBUM

Released in 2000 to commemorate the album’s 20th anniversary, Is There Anybody Out There? The Wall Live 1980–81 compiles the best songs from the 1980 and ’81 shows in London, with the addition of a master of ceremonies and two songs that didn’t make the final studio album: What Shall We Do Now? and the instrumental bridge The Last Few Bricks. Waters was reportedly against its release, but was outvoted.

LIVE IN BERLIN

To commemorate and celebrate the fall of the Berlin Wall in 1990, Waters created and staged a massive all-star performance of The Wall in Berlin’s former “no-man’s land.” A long list of guest artists including Van Morrison, Sinéad O’Connor, Cyndi Lauper, Marianne Faithfull, The Scorpions, Joni Mitchell, Thomas Dolby and Bryan Adams played for a crowd of 350,000, performing with a cast that included Albert Finney, Jerry Hall, Tim Curry and Ute Lemper. The show aired on TV in more than 60 countries, and a live album and video of the concert were released.

THE BOX SET

As part of the Why Pink Floyd…? reissue campaign in 2012, The Wall was refurbished, expanded and reissued in various configurations — including a six-disc box set that included dozens of original demos, a DVD of related video footage and various memorabilia.

THE WALL LIVE

Two decades after the Berlin show, Waters launched The Wall Live tour, which opened in Toronto in September 2010 and played 219 shows around the globe over the next three years. Updated and reimagined, it no longer focuses on rock-star alienation, incorporating a strong anti-war theme instead, reflected in the new concert film Roger Waters The Wall and its accompanying soundtrack. During a 2011 performance at London’s O2 Arena, Waters was joined briefly by guitarist Gilmour and drummer Mason, marking the first Pink Floyd performance since Live 8 in 2005 — and their last appearance to date.