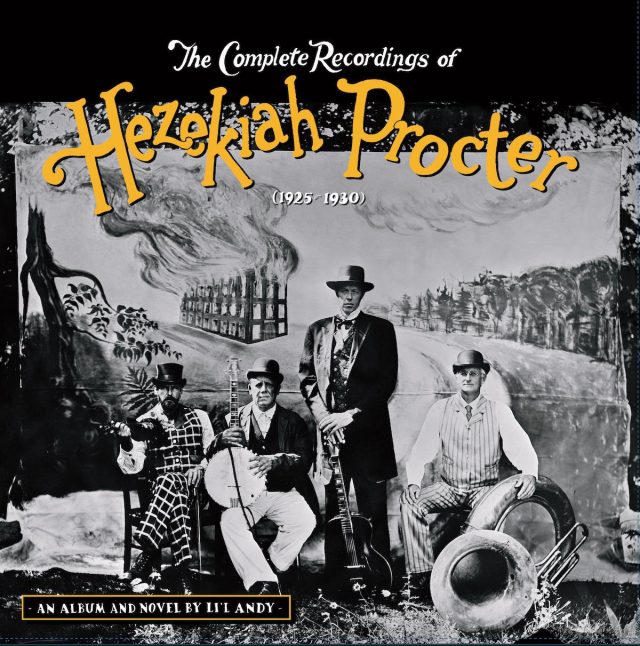

THE EDITED PRESS RELEASE: “Montreal singer-songwriter Li’l Andy’s latest project The Complete Recordings of Hezekiah Procter (1925-1930) is at once music, history, fiction, biography and recorded performance art. A two-disc, 29-song box set also including a 150-page novel telling the story of Hezekiah Procter, the tracks were painstakingly recorded on both analogue tape, and using pre-electric, 1920s technology. Overall, it is another stunning example of Li’l Andy’s boundless artistic ambitions and pure love of early North American roots music.

Until recently, little was known about the singer who most often called himself Hezekiah Fortescue Procter. From 1925, until his mysterious disappearance in 1929, Procter recorded some of the earliest examples of country, jazz, and old-time music and set the blueprint for the modern country star: cantankerous, talented, self-destructive — and perhaps a murderer.

Who is Hezekiah Procter? “He’s a completely fictional country musician that formed in my head over the past 10 years,” Andy says. “As soon as I started playing guitar when I was 11, I loved listening to Hank Williams, Jimmie Rodgers and Charlie Poole. I got sucked in as much by the music as their stories, the mythologies that built up around them. What made them burn out and fade away so young, so sadly, so mysteriously?

“That made me wonder: Could you create some kind of über-roots musician, that kind of untrained, self-destructive genius who makes a handful of great recordings, then disappears from history so that 78rpm collectors and archivists obsess about him? That’s who Hezekiah is. He’s a medicine show performer from the 1920s, one of those singers who was there when phonograph companies began recording “hillbilly” music, a folk hero, a Marxist who writes union ballads for striking labourers. He’s also maybe a sell-out, and a murderer.

“Once he formed in my imagination, I began to write songs as him. And while I wrote those 30 or so songs, I realized I had to write his life story to understand him more. So I wrote a biography of him, which took the form of fake liner notes to a box set of his collected recordings. That grew into 150 pages. When it came time to record Hezekiah’s songs, I realized I needed to record them on equipment from the 1920s or 30s. I hate modern, digital recording anyway — it’s too clean and transparent — but to use it on this project in particular would’ve ruined it. So we managed to record on a Webster-Chicago wire recorder made in 1937. And while recording I began acting as Hezekiah, developing his vocal mannerisms and archaic guitar style.

So now, when I perform live, I am him. In my singing, the banter between songs, everything. It’s old- time country performance art. It’s extreme vintage recording. It’s experimental fiction.

“From the start, I wanted this project to be a compilation of the complete recordings of an obscure country or folk or “hillbilly” singer — the kind of retrospective box set or two-disc set that comes with a thick booklet recounting the singer’s career with archival photos, like the kind Bear Family Records or Smithsonian Folkways put out. But when COVID hit, I suddenly had a lot of time to just sit in my studio and write. So the ‘liner notes’ became a novel. And the songs became a part of Hezekiah’s life story. And writing songs as Hezekiah became a madcap quest to find functioning recording gear from the ’20s or ’30s so we could make an album that sounded like old 78 rpm records.

“Finding recording equipment from the ’20s or ’30s that still worked was a challenge! And finding anyone who knew how to operate it. I talked with archivists at the Smithsonian in New York. I wrote to 78 rpm record enthusiasts in England and Germany who still cut to wax or lacquer. But … nothing I heard sounded really good. I think that recording on that gear is a lost art, sadly. At practice one day, I was complaining about it to my drummer Ben Caissie. And he said, “You should try a wire recorder!” I hadn’t heard of a wire recorder, but Ben explained: “It’s this machine they made in the ’30s. It records on a reel-to-reel like a tape machine, but instead of tape spinning by, it’s this razor-thin band of steel wire. It’s steel, so it doesn’t degrade and become unplayable over time like tape.”

“That sounded promising. But we didn’t have one. Ben set up a Kijiji alert for “wire recorder” and after about a year, he saw one listed for sale in Quebec City. That night he hops in his car, drives to the address the guy gave him over the phone, and arrives at this huge cathedral. The guy selling it was the caretaker of a Catholic church and they’d used the wire recorder to record sermons in the ’30s and ’40s! Ben bought their 1937 Webster-Chicago wire recorder, and when he was leaving, the caretaker said: “Here, you might as well take these too!” and gave him dozens of wire reels to record on. So that’s what we recorded the takes on: we taped over hours of sermons to make this album. Between takes, we’d listen to the voice of a Roman Catholic priest sermonizing in French as we cued up for the next song.

“The other challenge was writing songs and a novel at the same time. It made the revision process dizzying, a minefield. Every time I changed a line in a song, I’d have to go back to the novel and change something in the text. Every time I changed something about Hezekiah’s character or backstory, I’d have to think: “OK, does that make any of the references or lyrics in the songs ring false?” It was a constant back-and-forth for months and months.

The most rewarding thing about this album was realizing that I can write songs as another person, from a point of view other than my own. I started writing songs when I was 11, and I quickly got bored with the idea that a singer-songwriter has to pour out their “deepest, darkest feelings” in their songs and write heart-on-sleeve lyrics, as people say.

“Getting away from that cult of authenticity, which we totally fetishize in folk music, has been liberating. Particularly today, when “authenticity” is just another marketing strategy, be it in country music or on Instagram. We shouldn’t be asking: Is this artist the ‘real deal’? Do they have the correct life story and background to play this music? We should be asking: Are the songs good? That’s what The Complete Recordings of Hezekiah Procter is all about. Saying, “Is this idea of authenticity getting us anywhere closer to making good music, good art?” Or is it possible to make good art from a point-of-view that’s completely fabricated and imagined? As a guy from Montreal in 2022 imagining the life of a string-band musician from 1920?”