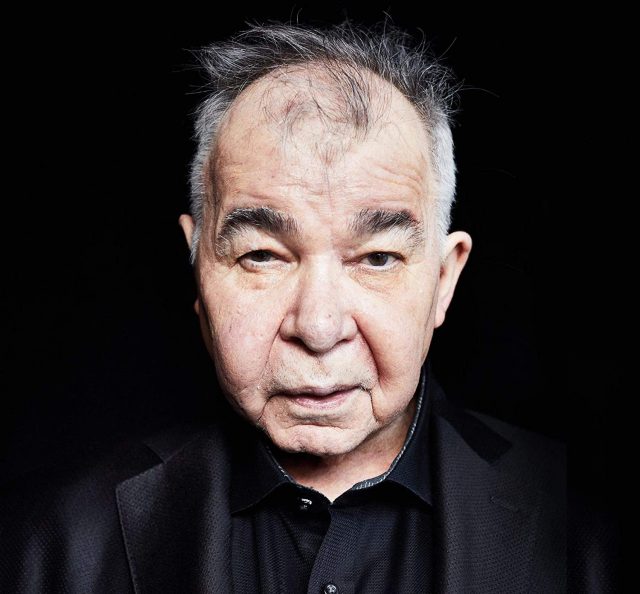

I was lucky enough to speak to John Prine back in 2012, shortly after he turned 65. He was every bit as charming, dry-witted and openhearted as you’d expect from his music. Since April 7 is the anniversary of his 2020 death from Covid, I’m putting it on the front page again. This transcript is a lot longer than the original print version. RIP John. You will be missed. You will not be forgotten.

They don’t make ’em like John Prine anymore. But he reckons they’re about to start.

The dearth of topical singer-songwriters in today’s music scene is just the calm before the storm, predicts the 65-year-old folk legend. “I don’t think it’s too far around the corner,” says Prine in a rare interview from his Nashville home. “Pretty soon you’re going to hear somebody that sounds like a new Kris Kristofferson or a new Bob Dylan or a new John Prine.” After pausing to consider those words, he ruefully quips: “I don’t know what I’d do with a new John Prine.”

Who can blame him? After all, the old one has been doing just fine lately. Four decades after quitting his mail route for music, the Chicago native remains one of the most revered songwriters of his generation. Especially among other songwriters. From peers like Dylan and Kristofferson to unlikely suspects such as Roger Waters, they’ve all sung the praises of his rich repertoire, which runs from evocative ballads like Sam Stone and Angel From Montgomery to witty ditties like Dear Abby and Illegal Smile. And while a bout with throat cancer in 1998 left him with a gravelly delivery, it hasn’t silenced him: Prine and his backing duo still spend a good chunk of the year on the road. On the eve of a Canadian tour, the affable folk legend called up to shoot the breeze about songwriting, the unbelievable Leonard Cohen and his idea of heaven.

Congratulations on turning 65. How’s that treating you?

Well, I was never 65 before, so I don’t have anything to compare it with. I know 40 sure felt good. I hear people moaning that they’re going to turn 40. I’d love to be 40 again. And when I look back to when I was a kid, I don’t remember any of my dad’s friends being 65 years old. I don’t think my grandfather made it to 65; I know my dad didn’t. People back then that were 65 didn’t look or feel or weren’t as active as we are now. It’s a different world now, you know.

A lot of artists your age complain about all the traveling.

You know, I think I’m finally getting used to it! I don’t book really gruelling tours anymore. And I’m not out looking for the best party in town. Now we’re just out doing the shows.

Has the music meant more since your health issues?

Everything means more. I’ve got two smaller children. Both of my them were born within a year and a half after I got diagnosed. They were very small. It was about a year before I got done with all the treatments and surgeries, and then a year after that until I was able to go on the road and sing. I’ve been enjoying it ever since. As a matter of fact, I have to go this weekend to Houston for my annual checkup. These days, it’s just to have them go, ‘Get out of here. We don’t need you. This isn’t the place you need to be.’ That’s good to hear every year.

How do you pick a set list these days? Is it based on what fans want to hear or what you want to play?

Well, I have certain songs I try to hit. For some people in the audience, it might be their first show — or their first show in 15 years. So I don’t ever do a show without Sam Stone and Hello in There. Fortunately, I’m not sick of them. But there are others where I’ve got to watch it, like Dear Abby. It’s the same two chords over and over. I can’t always sing that and make it seem fresh.

Does most of your material hold up well after all these years?

It holds up surprisingly well, even subject-wise. Take (Vietnam vet ballad) Sam Stone. If I had to place a bet when I wrote it, I would have thought that in five years I wouldn’t have been able to sing that sort of topical song. I thought times and situations would have changed. But the people that were touched by that conflict didn’t go away. So I don’t feel like it’s a nostalgic song.

You’re lucky; a lot of writers are embarrassed by their earlier material.

I know. But I’ve recorded songs I wrote when I was 14, and they sound the same as ones I was writing at 25. It came easy to me — so easy I didn’t think my songs were real songs. I was just having fun. I never harboured a desire to travel around the world and play my out-of-tune guitar and sing. I never thought that was even possible. I was just floored that people paid me to sing.

But it’s been years since we heard new songs from you. Do they not come as easily anymore?

Well, the writing, once I get into it, there’s nothing hard about that. It’s the desire. It used to be the only thing I had to do was think about songs. Even when I was a mailman. That job required no great skill, so once you got it down, you had a lot of free time to daydream and make up songs. What’s changed is 40 years of having it as my job. Now I need a carrot on the end of the stick to get started. But the guitar and the typewriter are sitting there.

With two smaller kids, you obviously have better things to do than make another record.

Well, I notice too that when I do put an album out, I don’t want to put something out just to have a new album, just so I can say I put out a new album this year. I want to have songs that I’ll continue to sing for a while. My live show is almost two and a half hours, and I don’t drop any songs, so when I go out to promote a new record, I have to find a way to fit all those new songs in.

You were one of the first artists to start your own record label Oh Boy. How did that happen?

Yeah, I did that in 1984. It came about not totally out of need. What I mean is, it wasn’t because I looked around and couldn’t get signed. I was just tired of record companies. I found them one of the most distasteful parts of the whole business. I really enjoyed the road and meeting people and talking to people and moving around and playing, for the most part. But the record companies … I’m not blaming them. I just don’t think that what I do lends itself to what they do. Because I met some really good people along the way at Atlantic Records and Asylum Records and Columbia and Sony. And there were people I really looked up to because of records they’d made and had a part in doing over the years and the artists they’d worked with. But I always felt like whatever company I signed with, they were basically scratching their heads and saying, ‘What do we do with this?’ They were trying to handle it like a regular pop record. And I always went against the grain, so they’d have to come back and explain that they couldn’t get me played here or there. I always thought they were doing something wrong. So I figured I would just go straight to the people who afford me a living — the ones who pay my rent — and cut out the middleman.

You were way ahead of the pack. Everybody’s doing it now.

When we did it — especially because things weren’t going bad with my old deal — some people told us we were crazy and committing commercial suicide. We were totally surprised how well it worked. The first album on Oh Boy was Aimless Love and we followed that up with an album called German Afternoon. It was named after the beer we were drinking in the afternoon while we were recording. And while we were recording it, people were already sending in cheques for it. We had the record paid for while we were cutting it. And I figured out that the amount of money the record companies give you is just a really high-finance loan. That’s all coming out of your pocket. And like I said, that would have been fine if they knew what they were doing in my case.

Your songs are often very literary and very narrative. Did you ever write fiction?

I never did. The only think I was ever interested in in school — and this also comes under the category of entertaining myself — is what I believe they called short shorts: Short pieces of fiction like you read in magazines. And I really liked dialogue. I once did this exercise for English class where you had to just write a few pages of dialogue. You couldn’t use ‘he said’ and ‘she said.’ The reader had to be able to distinguish what character was talking just from the things they were saying. I really enjoyed doing that.

You’re ending this Canadian tour by taking part in a Leonard Cohen tribute in Toronto. What does he mean to you?

He’s one of the few people I think is a poet. And he’s always been committed to doing his best. Even now. I went to see his show and could not believe it. I never would have thought I would sit through three hours of Leonard Cohen and not even want to go get popcorn because I didn’t want to miss a moment. I met Leonard years ago in Hollywood at a bar down the street from the Troubadour. I’d always liked him and he let me know right there and then he was aware of my music. So it’ll be nice after all these years to pay tribute to him.

What’s next after this?

I’ll take a break and go over to Ireland with my wife and kids for July. We live in a little town two blocks long, and they have 11 pubs. It’s darn near heaven.