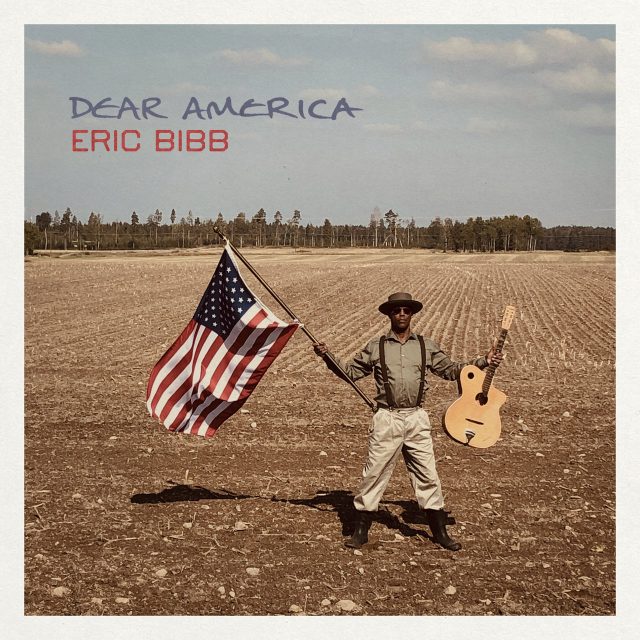

THE EDITED PRESS RELEASE: “Eric Bibb has known many different Americas — the good, the bad and the ugly. Born in New York City in 1951, the thunderbolt of the ’60s folk revival remains an era so alive in the 70 year old’s memory that he can still recall the idealism on the night air of Greenwich Village and picture Bob Dylan standing in his living room. Yet just as vivid are the dark societal flashpoints of the last year, when protesters highlighted the open wound of U.S. race relations while a bitter presidential election scrawled jagged battlelines.

Fiercely literate and historically informed, Bibb is a global citizen whose U.S. motherland — with all its pain and shame, hope and wonder — has bled into his art at every juncture since 1972’s debut album Ain’t It Grand announced him as a new force in blues, folk, and any other genre he cared to alight on. The Grammy-nominated singer-songwriter has perhaps never addressed the United States — or shone a light on himself — with such focused eloquence as Dear America. “On this record, I’m saying all the things I would want to say to somebody dear to me,” Bibb considers. “But it’s a self-portrait as well.”

If you could call out to your country, what would you say? When Bibb embarked on the title song that would galvanise the Dear America album, the songwriter found himself unpacking a seven-decade relationship with a partner of dramatic extremes. “It’s a love letter,” he explains of the record’s root concept, “because America, for all of its associations with pain and its bloody history, has always been a place of incredible hope and optimism. To be American, and particularly to come from New York City, is to be blessed.”

In November 2019, the bandleader hit Brooklyn’s Studio G to track Dear America with producer/co-writer Glen Scott and a crack studio band. “It was a kind of cosmically orchestrated series of events,” he reflects. “I was so pleased to record with Ron Carter, who I have an early connection with through my dad. Tommy Sims was all over the sessions, a wonderful bassist who I’ve worked with before in Nashville. I’ve played with many great drummers, but Steve Jordan has that authority: It’s just about the hit, man. As for Eric Gales on Whole World’s Got The Blues — he was just sublime, probably the most powerful electric blues player right now.”

Destiny is a glib concept, but from his earliest years, all the signposts were pointing Bibb towards a life less ordinary. His father, the late Leon Bibb, was the big bang that set it all off: A charismatic singer, actor and leader of men, who marched at Selma with Martin Luther King in ’65, moved in the orbit of social earth shakers like Bob Dylan and Paul Robeson (Eric’s godfather), and brought home the ethos that art was more powerful when imbued with real life. “My dad was the door to the world that I live in,” nods Bibb, who took ownership of his first acoustic guitar aged seven and never put it down. “That whole connection between music and forward-thinking social movements has always been at the bedrock. I never ‘decided’ I was going to be a writer of socially pointed songs. It was intrinsic. It has to be there. I write what I see.”

There are lighter songs across the tracklisting, stresses Bibb, pointing to the benevolent chug of the locomotive-themed Talkin’ ’Bout A Train, or the graceful opener Whole Lotta Lovin’, with its heartfelt salute to the American roots music that put him on his path.

On the wistful Emmett’s Ghost, he revisits the appalling murder of Emmett Till, whose incendiary lynching in 1955 galvanised the civil rights movement. “That song was written before the George Floyd case,” he explains, “but it feels like it has particular resonance right now.” Meanwhile, on the glowering Whole World’s Got The Blues, Bibb puts an ear to the ground to tap the street-level malaise in his homeland and beyond.

“This album is a love letter,” Bibb says again, “because all of America’s woes, and the woes of the world, can only come into some kind of healing and balance with that energy we call love. That’s my conviction. You see young people now and it’s amazing, with the whole Black Lives Matter movement. All of those things let me know that there is a kind of reverberation from that ’60s energy. You can’t keep a good thing down. Now we’re at that ‘watch and pray’ moment, and it’s an incredibly inspiring time to be writing songs…”