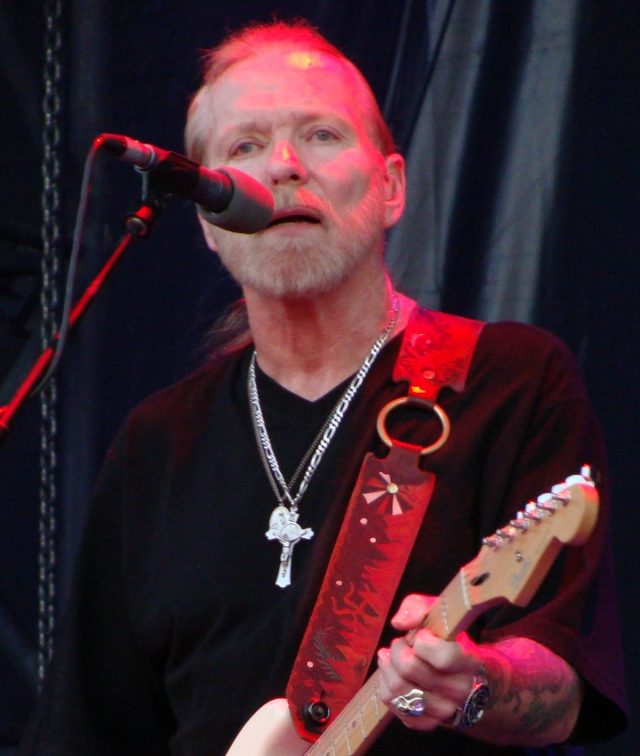

Back in 2011, I was lucky enough to talk to the one and only Gregg Allman. At the time, the southern rock icon was in a good place, recovering after a liver transplant and looking forward to returning to the road in support of his T-Bone Burnett-produced comeback album Low Country Blues — which sadly turned out to be his last studio release before his death in 2017. Since today is the 50th anniversary of the release of The Allman Brothers Band’s breakthrough concert album Live At Fillmore East, it seemed like a good day to pull out chat out of the archives, and toss in a few extra quotes that didn’t make it into print the first time around. Enjoy.

Gregg Allman is still a ramblin’ man. Nearly nine months after a liver transplant gave him a new lease on life, the southern-rock legend is eager to get back on the road and start playing up a storm again.

“Hell yeah, man,” the 63-year-old singer and multi-instrumentalist enthuses from his home in Savannah, Ga. “I can’t wait. I’m not really finished healing yet. They say it takes about a year and a half before you’re back to your old self. I still have residual pain everywhere. It pops up here and there — mostly in the morning when I wake up. But it gets just a little tiny bit better every day. So as long as I get plenty of rest, I should be OK.”

Allman might need to book a few extra naps, judging by his schedule. First he reteams with The Allman Brothers Band for their 22nd Beacon Run, playing 13 shows in 17 nights at the famed Manhattan theatre beginning March 10. Then he barnstorms North America and Europe with his own band to promote Low Country Blues, his first solo CD in 14 years. Not bad for a guy who was facing death last year. Then again, Allman has always been a survivor. Decades of addiction and drug busts, the back-to-back deaths of his guitar-hero brother Duane and bassist Berry Oakley in motorcycle crashes, half a dozen broken marriages (including four years with Cher) — you name it, he’s endured it.

With his new disc garnering rave reviews, a tired-sounding but upbeat Allman endured a few questions about medicine, music and breaking in producer T-Bone Burnett.

This has been a very eventful year for you.

No doubt. And a painful one!

How long were you on the transplant list?

Five months and five days. The last three weeks at the top of the list. That was excruciating. I started to think it was a joke — that they weren’t going to find me no liver. And it was life or death. I had four tumours on the bottom lobe of my liver. But they keep you away from the old D-word, you know. They don’t tell you any bloody stories or how it’s going to be afterwards. So I went into it whistling and singing. I was really happy the day they found me a liver. And when I woke up afterwards, I was even happier.

You made the album before the surgery. How did your condition affect the music? Did it add an urgency to the proceedings?

It really didn’t, you know. Not at all. For me, music takes over — and takes all. It’s like a solace.

But was it physically tough to make the album? Were you able to do everything the way you wanted?

Well, I was a little weak. But I had been for a couple of years, already. I would have to sleep a good 10 hours to play a show that night. It’s still that way. But all that’s going to change.

I understand you didn’t know who T-Bone Burnett was before this album. What convinced you to work with him?

That’s right — I never even heard his name. After my producer Tommy Dowd died in 2002, whenever the subject of recording came up, I would just go hide. I wasn’t interested in breaking in a new guy. But I agreed to meet T-Bone in Memphis. He was there with two carpenters, measuring the Sun Records studio board for board so he could build an exact replica next to his house in Santa Barbara. I thought, ‘Man, that is the hippest thing I ever heard of.’ And then, the first thing out of his mouth was about how great Tommy Dowd was. So little by little, I started to think this guy might just do. And when I got to his studio and saw who was in the band … Dr. John was there, playing up a storm. I’d worked with him on my second solo record. We even wrote a song together. He’s been a long-time friend. Hell, my brother and Mac were good friends. That’s how long I’ve known him.

The album is mostly blues covers. How come? Weren’t you writing because of your condition?

Well, I did write one on there. And I have plenty more. We just wanted to follow a certain theme. We talked about it. Some guy had given T-Bone a hard drive with thousands of songs. He said, ‘I’m gonna peel off about 25 and send ’em to you. You pick 15 and put arrangements on ’em. Let’s do ’em your way, but bring ’em up to date.’ So that’s what we tried to do. And then we cut it all on tape.

Now that you’ve broken T-Bone in, are you willing to work with him again?

I can’t wait to do it again. As soon as I get a little more energy, I’ll be in the studio. And maybe it’s a little premature to tell you this, but I’m going to try to get him hooked up with The Allman Brothers for our next album. That would be great.

Do you have a lot of regrets about your life?

Well, would it help? But yeah, I do. Somebody asked me the other day: If I had to do it all over again, would I change anything? I said, ‘Yeah, the drugs and alcohol.’ You just feel bad all the time — you feel bad when you do the shit, you feel bad when you don’t. That’s how it got for me. Now I’m 16 years clean and sober and I try to get to some of these young players. If I can save just one from that hell, it’s worth it.

It’s been 40 years since Duane died. Do you have any plans to mark that?

We’ll probably dedicate the Beacon set to him. And we always say something about him at New Year’s and his birthday. That’s about it. We don’t overplay it.

But you must think about how things would be different if he were still around.

Yeah. I don’t know though, man. On the one hand, I don’t think the band would be together anymore, ’cause he was so good. Even in death, they rated him No. 2 in the world. Just one behind Jimi Hendrix. That’s a pretty good feat there. So he probably would have left us at some point.