matthew sweet has read my mind.

or at least my books.

like please kill me.

from the velvets to the voidoids.

i’ve been reading them all again recently.

soadking up the stories of the early days of nyc proto-punk.

the days of television and richard hell.

the days of lou and lester and cbgb.

and guitarists like richard lloyd, bob quine and ivan julian.

you might not know who they are.

sweet does.

and not just from books.

he’s worked with all three of them.

learned from them.

been influenced by them.

and he pays tribute to them all here.

in his own way, of course.

which is to say: this is not sweet’s punk album.

it’s old-school rock and power pop.

glam and paisley jangle.

beatle-pop and neil young folk-rock.

and echoes of everyone from t.rex to big star.

but every song is loaded and laced with fantastic fretwork fireworks.

looping, loping licks.

piercing stilleto solos.

it’s nostalgic and old-school.

a throwback for sure.

and a must-have for anyone who loves marquee moon.

but somehow it suits the times perfectly.

especially with that richard hell destiny street reissue coming out next week.

looks like sweet read somebody else’s mind too.

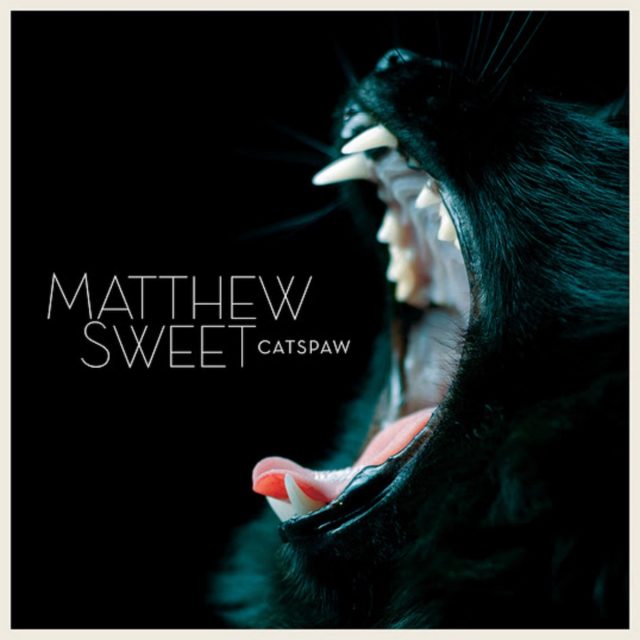

THE EDITED PRESS RELEASE: “Before the gold and platinum albums, before the MTV hits and critical renown, power-pop and alternative-rock pioneer Matthew Sweet was just a 13-year-old bass player sitting alone in his Nebraska bedroom, daydreaming of a life spent making music. “I was just starting to write songs and play a little guitar and I had this thought: I wonder if when I’m old and I’ve been around music a really long time, I might suddenly just be able to play lead guitar without ever properly learning how. Maybe if you just play a really long time, it just kind of comes together? And the funny thing is, it did. I’m able to.”

On Catspaw, his 15th studio album, Matthew Sweet cranks his vintage amplifiers and steps into a role previously played by some of his generation’s most unique and incendiary lead guitarists from Richard Lloyd (Television) to Robert Quine (Lou Reed) and Ivan Julian (Richard Hell & the Voidoids). Though Catspaw is absent of his famous collaborators, their presence is felt in the mark they left on Sweet’s guitar work. His solos are audacious, confrontational, and inspired.

“I play free form,” he says. “Nothing is too labored over and that was important. It’s spontaneous. The more you can do that, the more organic it is.” He refined his style over decades of collaborating with great guitarists. “Richard’s [Lloyd] playing influenced me a lot — the ambition he has, that feeling when he just lets loose. I not only related to the approach, I related to it musically. I was also developing my ear over time. Now I can hear where I want a lead line to go.”

Catspaw is guitar-driven: 12 songs, lean and consistent, direct, and notably darker than Sweet’s recent song-cycles. Apparent in tracks like Best of Me and album-opener Blown Away, the inner-turmoil harkens back to the angst of 1993’s Altered Beast. But where Beast was the self-interrogation of an artist in his mid-20s, Catspaw is the confessions of a career artist, mature and assured in his craft and achingly transparent in his confrontations of aging and the search for meaning. “I’m trying to get my head around getting older, I want to let go, I want to tell the ugly truth … I want to do all kinds of different things in my head and they really popped out in these songs.”

In true Sweet fashion, Catspaw’s mischievous title was born from equal parts grappling with his own mortality and some television obscura from his childhood. “I learned the term from a 1967 Star Trek episode I adored as a kid. (The storyline features a gigantic feline villain.) “Recently I heard “catspaw” again and started looking up definitions. I really connected to the idea of the certain and deadly inevitable — the pounce. Don’t ever forget life is totally cruel and the catspaw is already coming down on you.”

But despair is not the conclusion of Catspaw; one song, Challenge the Gods, urges quite the opposite. “That song is about defiance. I’m saying, ‘to hell with fate and gods and things like that.’ Like Dylan Thomas said, ‘Rage against the dying of the light.’ ” Bolstered by a layer of chugging rhythm guitars, this pick-me-up anthem is his I Won’t Back Down — “Rise above, take your place / Punch the world in the face,” he sings.

Catspaw was finished just before COVID-19 struck, but tonally it feels right on time. “It really feels like the fruit of the pandemic,” says the artist. This is at least partially due to how it was written and recorded: aside from excellent drumming by longtime collaborator Ric Menck (Velvet Crush), this is Matthew Sweet’s first entirely solo effort. Sweet handles all of it: recording, mixing, Höfner bass, electric guitars, and Pet Sounds-like background vocals. Catspaw was recorded in his beloved home studio, Black Squirrel Submarine (named in part for the dark wooden interior). Prefiguring the quarantine and social distancing era, Sweet has created something whole and beautiful within the confines of isolation. It’s a testament to the potency of art-making in solitude.

“For me, being an artist is ultimately a solitary thing,” he allows. “I’ve taken comfort in that as I’ve grown older. Success and people come and go in life, but I know I will always be making music and that it continues to be fun and intriguing — that mystery of discovering what a song is going to become.” Catspaw is the latest product of a remarkably fertile period that began when Matthew and his wife returned to his native Nebraska in 2013 after two decades of living and working in the Hollywood Hills.

While recent efforts Tomorrow Forever (2017) and Tomorrow’s Daughter (2018) derive their strength from a diversity of textures and moods, Catspaw strikes with a uniformity of intent and focus. The soft, natural psychedelia of Drifting and Hold on Tight provide subtle shifts in landscape, while the longing of Come Home once again reiterates Sweet’s uncanny ability to capture the wavelike motion of heartache. Overall, these songs create a pleasing sensation of a prolonged, happy blur. The effect is reminiscent of Cheap Trick’s debut LP or Big Star’s Radio City, products of a bygone era of record-making when long-form flow and coherence — the exact amount of time it took to share a joint with a friend or build up the courage for that first kiss — were essential to a successful album.

“I realized after I’d finished the record that I had made it just after turning 55 and that was coincidentally the exact age I fantasized I would be all those years ago when I was hoping someday I’d be able to play lead guitar on my own album.”