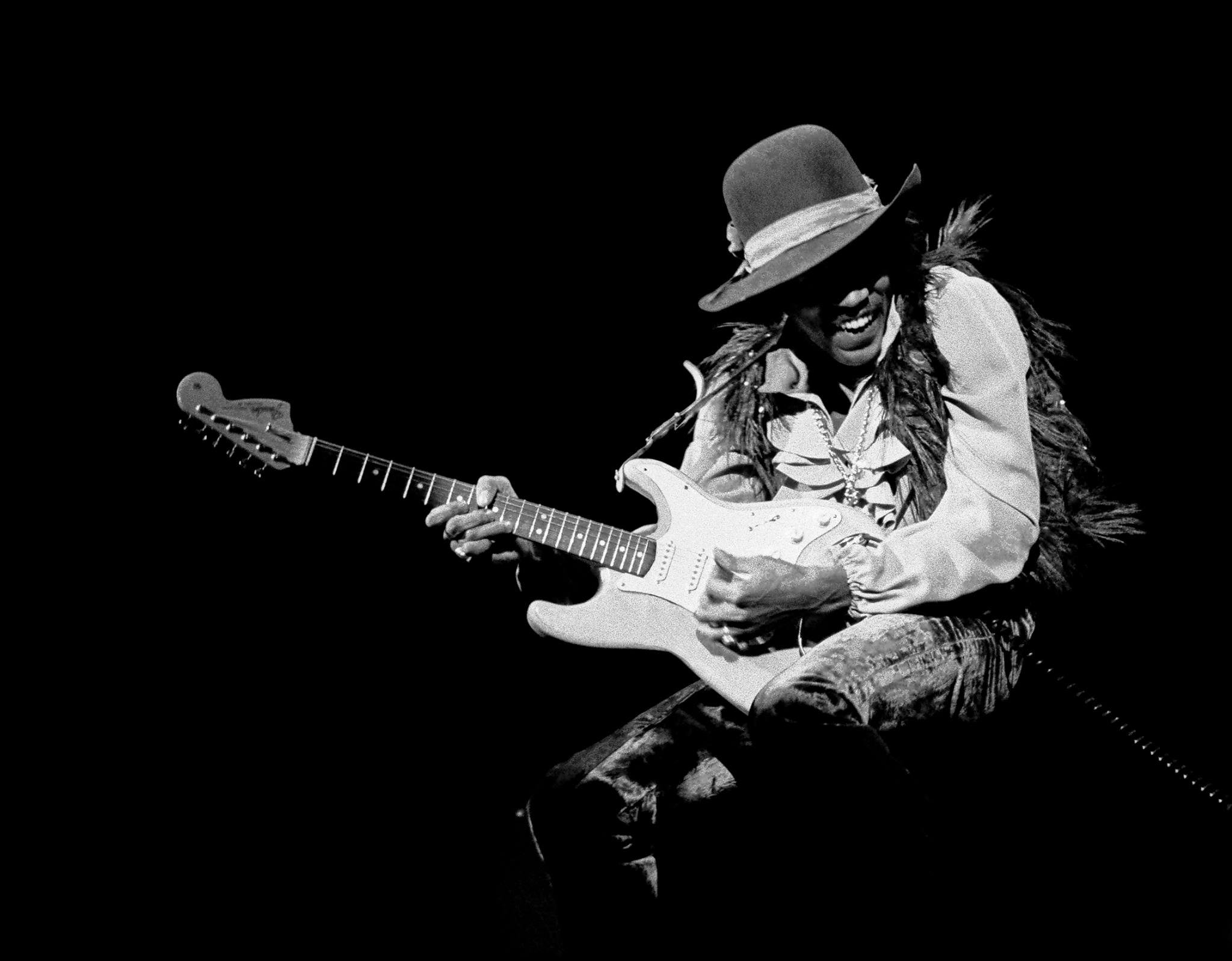

Nov. 27, 2022 would have been Jimi Hendrix’s 80th birthday. Here’s a slightly edited version of a feature I wrote back in 2010 to mark the 40th anniversary of his death:

The Monterey Pop Festival was an experience Steve Miller won’t soon forget. It was there, on June 18, 1967, that he was first saw Jimi Hendrix.

“When I first saw him I thought, ‘Gad, he looks like Eartha Kitt with a guitar. This is really far out. Who is this guy?’ ” recalls Miller, who also played the California festival. “Then I went out and watched his set, and was knocked out.

“It was so cool I couldn’t believe it. He brought all those old blues and R&B traditions to the stage — playing the guitar behind his head like T-Bone Walker and biting the strings like Johnny (Guitar) Watson. You had never seen anybody look that cool, move that cool, act that cool, and kick everybody’s ass that hard with a trio. It was amazing. He was so far ahead of everybody, so free and so fluid and so much fun.”

Miller’s wasn’t the only mind was blown that day. Hendrix’s set — which famously climaxed with him dousing his Stratocaster in lighter fluid and setting it ablaze — was the charismatic performer’s first major American show. It heralded the beginning of a meteoric career that would turn him into the ultimate guitar hero in just three years — and ended with his death at age 27 in a London flat.

THE START

![By Unknown U.S. Army personnel - [1], as originally printed in a Fort Ord Training Center yearbook [2]., Public Domain, https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=30601047](https://tinnitist.com/wp-content/uploads/2018/09/Hendrix_Army.jpg)

James Marshall Hendrix’s story began Nov. 27, 1942, when he was born in Seattle. His childhood was not idyllic. Money was tight. His mother drank. Jimi shuffled between relatives, including a grandma in Vancouver. His parents divorced before he turned 10. When he was 15, his mother died. That was when he got his first guitar, a $5 acoustic. He played constantly, working his way through local bands. One fired him for his wild antics. He left school and found trouble with stolen cars. He avoided prison by enlisting in the Army in 1961, but his lack of discipline earned him a fast discharge. With Army bud and bassist Billy Cox, he hit the road, honing his chops on the Chitlin’ Circuit with Slim Harpo, Sam Cooke and Jackie Wilson.

By the mid-’60s, he was in New York, backing the The Isley Brothers and the flamboyant Little Richard (who would fine him $5 when he outshone his boss onstage, says Miller). Eventually, Hendrix — calling himself Jimmy James — formed The Blue Flames. They found a fan in Keith Richards’ girlfriend, who hyped them to Stones manager Andrew Loog Oldham and then Seymour Stein. Neither got Hendrix. But former Animals bassist Chas Chandler did.

THE U.K.

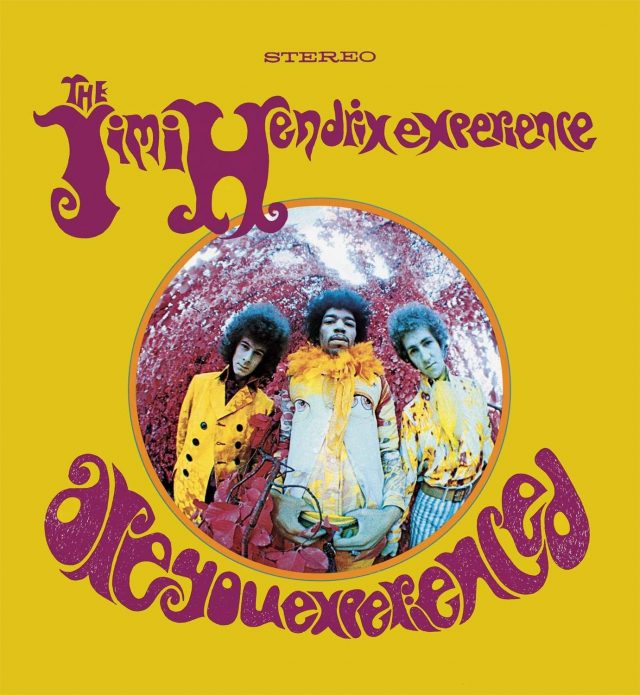

In 1966, Chandler and Animals manager Michael Jeffery signed Hendrix. They flew him to England, recruited drummer Mitch Mitchell and bassist Noel Redding, and The Jimi Hendrix Experience was born. The trio’s first single Hey Joe arrived in late 1966, followed by the LP Are You Experienced in spring 1967. They were cut at Olympic Studios, where Hendrix met the man who would become keeper of his sonic legacy: Eddie Kramer.

“Being in the studio with Hendrix was always a challenge,” says Kramer (pictured above), who engineered or produced virtually all his studio recordings. “You had to really be on your toes, because the direction could change at the drop of a hat. If a song wasn’t working out, Jimi would instantly go into something else. And the band and I had to know what he was talking about. He had a tremendous amount of concentration and a laser-like focus.”

They served him well. In 16 staggeringly prolific months, the Experience created the albums that anchor Jimi’s catalog: Are You Experienced, Axis: Bold as Love and Electric Ladyland. They yielded a list of immortal anthems: Purple Haze, Foxy Lady, Fire, Crosstown Traffic, Red House, All Along the Watchtower, Voodoo Chile (Slight Return). “They are all great,” raves Kramer. “From Are You Experienced — the coarseness and the roughness of that — to the most experimental moments of Axis and Electric Ladyland, which really kicked down the doors.”

Meanwhile, Hendrix’s dynamic gigs — which fused his pyrotechnic skill and groundbreaking use of feedback and distortion with his old-school showmanship — left both his peers and teenage fans gobsmacked. Among them: West Bromwich lad Ken Downing.

“I saw him when I was 16 for the first time,” says Downing, now better known as former Judas Priest guitarist K.K. Downing. “It was a life-changing experience, literally. I had a $15 guitar that was virtually unplayable. I was dabbling. But after seeing Hendrix and thinking, ‘This person is totally God,’ all I wanted to do was play his riffs. I saw him seven or eight times. I was totally in awe.”

The rest of the world would soon follow suit. For better and worse.

THE FAME

After Monterey, Hendrix’s star rose rapidly. Are You Experienced reached No. 5. He toured extensively. He even opened for The Monkees.

But fame and fortune brought problems. Groupies, dealers and leeches descended. The drinking and drugs increased. In May 1969, he was busted for drugs at Toronto’s Pearson Airport. The music suffered. Frustrated, Chandler left. The Experience weren’t far behind. Loyal friends were replaced by crooks, alleges Miller. “He didn’t have one person with education or brains around him. He was surrounded by punks and people who were just using him. Everybody just wanted to make money off him. He didn’t have any help. I felt very badly for him.”

After the Experience’s last show on June 29, 1969, Hendrix recruited Army buddy Cox on bass, added a guitarist and two percussionists, dubbed them Gypsy Sun and Rainbows — later shortened to Band of Gypsys — and played Woodstock, closing the festival with a now-legendary reimagining of The Star-Spangled Banner.

It was mostly downhill from there. He cut a live album with a new Band of Gypsys to settle a contractual dispute. He reformed the Experience without Redding. He talked about firing his manager and joining ELP. He noodled in the studio. He played memorably at the Isle of Wight. He played poorly at Madison Square Garden. Miller recalls their last gig, at Philadelphia’s Temple University:

“He was completely addicted to heroin and speed. He was controlled by the Mafia. We played just before Jimi. We finished our set and were moving our gear off the stage. I was picking out a spot near his monitors to sit down and watch him — anytime we worked together I literally sat on the stage watching him because he was such a magnificent musician. And this guy came up and said, ‘Get off the stage’ and pulled a gun on me. Those were the people handling Jimi.

“When he arrived, he stayed in the limousine for two hours, until $112,000 in cash was rounded up and given to his handlers. This was 1970, so that was like $900,000. It was a huge outdoor show and they held it up. When they finally came out to play, they smelled so bad I almost threw up. He had just shot up. He looked like he weighed 110 pounds. They looked bad, they smelled bad, they couldn’t play. They just made noise. All I wanted to do was just grab him and take him home with me and save his life. But you couldn’t get near him. He was dead four months later.”

THE END

Hendrix spent the evening of Sept. 17 at a party in London, ending up in a girlfriend’s flat. The next morning, his fully clothed body was found. He had reportedly taken too many sleeping pills, drunk too much red wine and asphyxiated on his own vomit. Rumours circulated that his manager had killed him for insurance money. Nothing was proven.

Hendrix was buried in Renton, Wash. Chandler died in 2006; Redding in 2003; Mitchell in 2008. The music lives on.

IN THEIR OWN WORDS

Here’s what some contemporary players had to say to me about Hendrix and his music.

Slash

“Jimi was fucking awesome. Wow. There’s so much stuff about him. I just appreciate Jimi Hendrix for being one of the most bitchin’, fucking rock ‘n’ roll-blues-soul guitar players of all time. Being ranked No. 2 behind him (by Time Magazine)? That’s bullshit. That’s sort of an embarrassment. I mean, it’s flattering, but come on.”

Josh Homme

“Hendrix has only been horrendously imitated. You listen to someone do Hendrix and then you listen to Hendrix, and they’re cavernously apart. Some of it plays like an alien who has no distance between his mind and his fingers. I miss not hearing what he would have done. In a sea of AutoTune and manufactured music, I would love to see him fuck shit up. We could use somebody like that.”

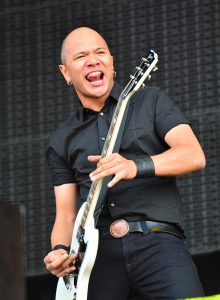

Danko Jones

“His impact on rock is so imbedded now, it’s hard to decipher almost. The use of distortion and feedback, the way he solos — it’s all been used by so many bands that it’s hard to remember he basically started all that crazy stuff. But for me, Hendrix represents something more than just the music. It was a black guy fronting a rock band. Up until that time, music had been dominated by white guys. I looked to him for inspiration on another level than just music. To be Jimi Hendrix at the time, doing what he was doing, I can only imagine how hard it must have been to get to the level he got to.”

Derek Trucks

“Everybody goes through a Hendrix phase. If you play electric guitar in our genre, you go through a period where you just dig into those records so hard. For me, he is that perfect collision of everything I love about Chess Records and Delta blues, along with that psychedelic period when there was great music being played, along with some late ’60s jazz, and The Beatles and Dylan. He took from all the right places, you know. It seemed he was dropped from space, but if you really trace it, you can hear all those influences.”

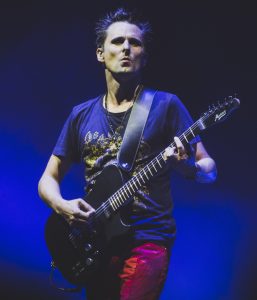

Matthew Bellamy (Muse)

“When I was growing up, I didn’t know that much about rock. I was more into jazz, blues and classical. But when I was 13, i saw a video of Jimi Hendrix setting fire to his guitar at Monterey. It just totally blew my mind. Both in terms of the theatrical side of live performance, but also the chaos and craziness of his guitar playing. The unpredictable elements of that really changed my perception of music. Up until then, my perception was that everything was very formalized and had to be done a certain way and written down. I didn’t really understand improvisation. But Hendrix took improvisation to a different level. He took it outside of actual music; he took it to his lifestyle in the way he dressed and the way he moved the guitar.”