I have interviewed Ian Astbury of The Cult twice (so far) — most recently in 2016 to promote the band’s latest album Hidden City, and back in 2011, when he was actually on holiday, but was kind enough to discuss his work with The Doors for a feature I wrote marking the 40th anniversary of Jim Morrison‘s death. Both times, he was incredibly helpful and talkative, giving me far more information than I could ever use in a single story. If you haven’t already read that Doors piece, you can find it HERE. Or you can read the full, unedited transcript or our 2016 chat below. I pulled it out of the archives because May 14 just happens to be Astbury’s birthday. Cheers.

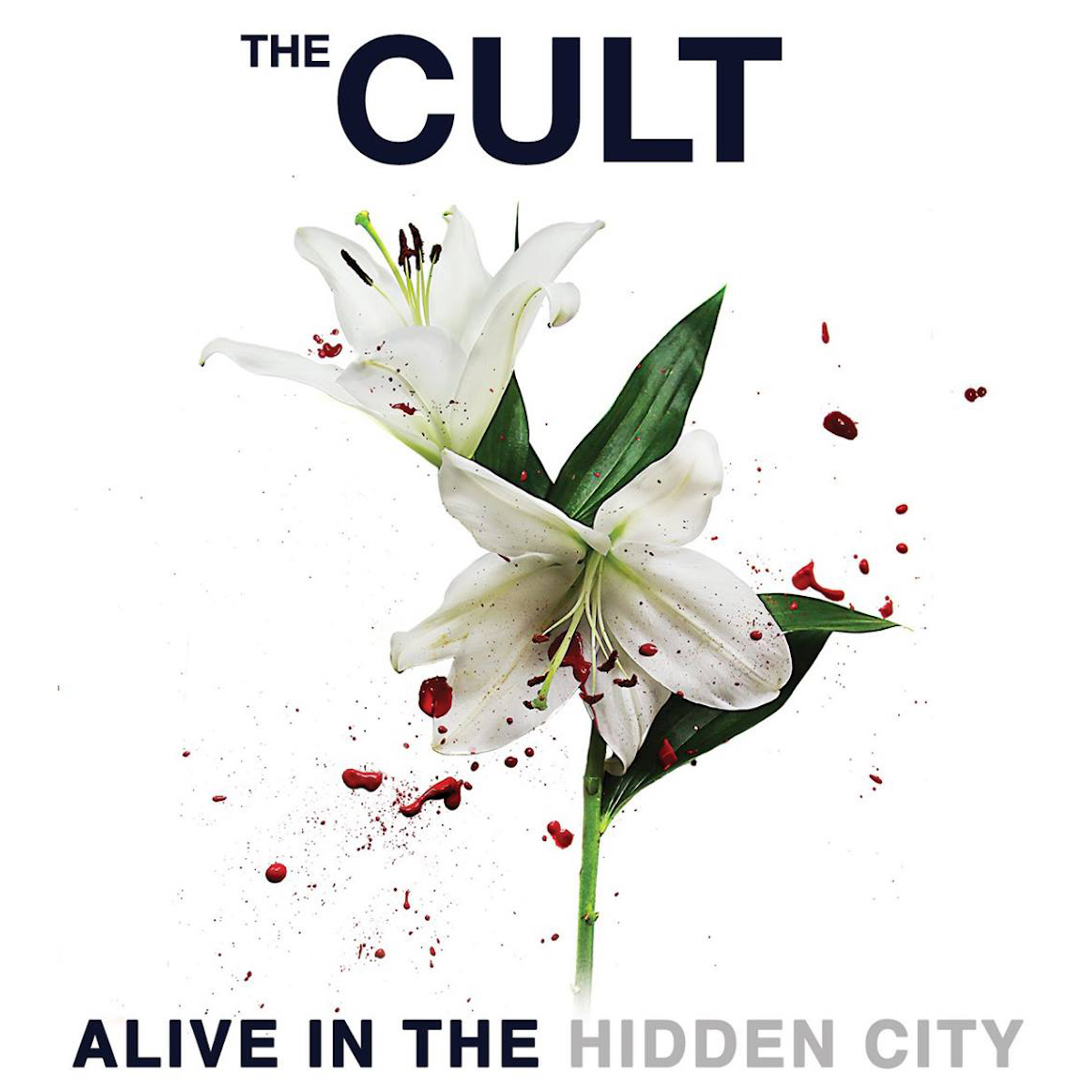

The Cult’s Alive in the Hidden City Tour has been a revelation to Ian Astbury. “These shows we’re doing now are so intense,” the frontman says from his home in Los Angeles. “The new material demands so much in terms of being present as a performer. We’re there in the moment — and we really leave everything on the stage.”

By ‘we,’ of course, Astbury is mainly referring to guitarist Billy Duffy, who has been his musical partner in crime through three decades, several lineup changes and a slew of classic hits like She Sells Sanctuary, Love Removal Machine and Fire Woman. For musical seeker Astbury, however, it’s not about looking back but moving forward. The duo’s 10th album Hidden City, produced by frequent co-conspirator Bob Rock, tempers their arena-rock swagger, crunching guitars and belted vocals with deeper grooves, a slower pace and moodier melodies. As the pair — augmented by drummer John Tempesta, bassist Grant Fitzpatrick and keyboardist Damon Fox — mapped their latest return to Canada, the onetime Hamiltonian weighed in the the cool north, their evergreen hits and going the difficult route.

I know it’s been a long time since you lived here as a teenager, but does touring Canada stir anything patriotic or nostalgic in you?

Oh yeah. I love seeing how Canada has grown up. Everyone is looking at Canada and going, ‘Can we all move there?’ It’s very cool. Trudeau is one of the coolest politicians out there, and obviously, what’s happening in Toronto with Drake and The Weeknd is great. Then you’ve got the Raptors and all the Canadian fashion and all the Canadian artists. Canada’s coming of age.

Do you still have citizenship?

No. I never actually had citizenship. I was a landed immigrant in Canada. The story’s kind of sad. We came over as immigrants in the ’70s — we lived in Hamilton — and my mother got cancer. She decided she wanted to go back to die with her family in Scotland. So we returned to the U.K. Then my mother passed away and my father decided to return to Hamilton. We were kids — I was 17, my sister was probably about 11 and my brother was 16. And we were given the choice of staying in the U.K.or following my father back to Canada. My brother stayed in the U.K. He was still at school. He just went to stay with a friend’s family and finished school. But my sister and I went back with my father to Hamilton, and when we arrived back in the country, the immigration officials said, ‘You can’t come in. You’re landed immigrants. If you’re out of the country for six months you effectively lose your landed immigrant status.’ So here we are, having gone through this really very difficult turbulent couple of years with my mother being sick. and we were refused admission. My sister and I were taken away and separated from my father, which was really stressful and no small amount of duress. My father was a Canadian citizen, but we weren’t naturalized. But eventually they let us in. And like I said, at that point I’m in my late teens, and punk rock is happening the U.K., where I made loads of friends. Hamilton was unfamiliar to me at that point. I’d lost communication with people and I didn’t really feel connected to it anymore. and i really wanted to be in the center of things and be back in the U.K. and music was very very important in my life. So I decided to go back. I spent a few months in Hamilton deciding and then I went back to the U.K. And within a year, I was in Southern Death Cult. And I haven’t really looked back since. But being in Hamilton was really a very formative part of my teenage life. It was really important.

Hidden City was billed as the completion of a trilogy. You worked with Bob Rock again. You played some shows with former tourmates Guns N’ Roses. It seems like things in your world have been coming full circle lately. Does it seem that way to you?

Not so much, because we’re not really taking stock; we’re just getting on with it. We’re trying to make choices based upon instincts. We’ve been offered a lot of opportunities to make money touring with artists who maybe had commercial and artistic successes several decades ago. But we choose not to do that. We still believe that we have a lot left to say. We’re driven and responding to the world we live in today. We don’t want to be a pastiche of what we did 20 years ago.

But obviously you’re playing some of your hits. What’s your relationship like with the older material?

Well, when you talk about something like She Sells Sanctuary, it’s basically three chords. It’s an archetypal song. It’s really simplistic. But the thing about that song is it rejuvenates itself every time we play it. There’s something in the DNA of that song; a certain earnestness and optimism. It’s anthemic. It rejuvenates. It holds its own space. In some respects it’s timeless. And it feels timeless when we’re playing it. It feels current. But then there are other songs we choose not to play because we don’t feel they’re representative of where we’re at right now. It’s all based on taking songs that perform a certain function or create a certain sentiment to form an overall narrative for the set. So we’re not just going to go out there and play Electric, Love and Sonic Temple. because those records were made at a time when the industry was in a different commercial place. These are albums that sold millions and millions of hard copies. So if you’re basing a set purely on commercial successes or if that’s your gauge for artistic importance or whatever, you’re going to completely limit yourself. And I think it’s disrespectful to your audience as well, implying that they’re just going to want to turn up and hear those three albums. Even when we’re gone out and played Electric live and Love live, we’ve imaged it as a current immersive event. We did Love live. We split the show so we played the record in its entirety. Then we show a film and reset, and then we have a completely different staging with a set of material that was more reflective of where we are now.

Some of the newer material seems deeper and darker.

Well, that’s always been there to a degree, if you go back to things like Death Cult. We play Horse Nation. We play Sweet Soul Sister. It has quite an elongated keyboard intro, and now we have a keyboard player, which allows us to link the songs. On this album, there are several songs with piano. And we are able to incorporate that in a live situation, which is something we’ve never really done before. But my voice is always going to be my voice. Billy’s guitar tones aren’t so dissimilar; he still uses amps and effects pedals that he’s used since the beginning of the band. It’s evolved, with new tones and sounds and instruments. But the basic DNA is still there.

You and Billy have spent decades in each other’s pocket. How do you make that relationship work?

We’re very different people. We have very different lifestyles and very different social groups and very different interests. But when we come together in The Cult, there’s just a chemistry that works very well. But it’s all about respecting space. And when you work in the studio with Bob Rock, he’s a great facilitator and diplomat and older brother. He plays all roles and is able to serve the song. The song becomes the most important element in the room and he directs the individuals in the room to achieve a vision which we all discuss and are all involved in. But he helps us to work through the difficult parts if we have a disagreement about something. He’s able to kind of work the process through and do what’s best for the song.

Do you and Billy disagree a lot?

We don’t really communicate like that. It’s more intuitive. We can kind of feel something out. It’s not so much a disagreement. Because we really communicate in an aural way, with what’s coming out of the speakers. You’re working with instinct. And maybe responding is a better way of looking at it. You respond to something. So if Billy threw something down, I would respond to it in a certain way. If I respond to it with disinterest, obviously that is not going to fly. But if I respond to it with some interest, then that is going to potentially grow into something like Birds of Paradise. Initially, Billy was opposed to — not opposed to, but the piano being in the room wasn’t a place he felt comfortable starting with. But I put piano in the room because piano in the room was going to liberate us and make us come at things from a different angle and allow for different voices, different areas, different emphasis. And eventually, the influence of the piano — sometimes directly, sometimes just the fact we’d opened up a whole new conversation with this instrument in the room — I think it kind of led to the breadth of Hidden City. It was really effective. So we work more intuitively like that. Billy may have a certain guitar tone like the one that inspired the song G.O.A.T., which on the surface, just appeared to be like a street-brawl riff. And very quickly, with the cadence of the song, the way the song moved, there was a conversation there. You’re really responding to environment and the immediacy of the the current culture. That song instantly started the conversation, but the conversation was like throwing down: Put down the riff, cut the song, arrange the song, come up with a breakbeat. And the lyrics came immediately. It was all done in pretty much two hours.

What is your role in the live setting when that sort of creation is happening?

Sometimes it’s not doing anything at all. Sometimes it’s just being witness, being present, holding the space, and not climbing the PA stack and jumping into the audience. It’s letting the other musicians speak. That’s something you pick up and begin to realize by spending time in dojos, spending time in ashrams, spending time in meditation, spending time learning the value of not doing. Because coming out of post-punk and new wave and then into blues-driven hard rock, we wanted to create a vehicle that would leave a real imprint on the audience and that we’d all have this kind of immersive experience together. It would be a live performance that would really leave everything on the stage. And everybody felt completely depleted when they left that building. That was our job.

How do you do it now?

Now it’s more refined. I think you find more ways of refining that experience. You have more control of the environment. You’re never going to see the same Cult show twice, even if we decide to play the same set list twice. It’s always going to be different. Shows can take a complete left turn. When we played the Palladium in Los Angeles with Primal Scream last year, it was just post-Bataclan. (The terrorist attack) was something that was really deeply shocking and felt really personal in a way. There was a sense with both bands that we felt really connected to that moment. That really shook us and we kind of brought that into our show, the idea that all of a sudden performance space had become a really volatile environment and certain freedoms had been challenged. So those shows were immersed with that energy and it gave the shows a different edge to it. The gloves kind of came off. There were a few incidents that occurred with security, with certain entitled members of the audience. I was trying to assist some people in the audience who were being crushed at the barrier. They were drunk and flipping me off; they didn’t want to be pulled out. But they were actually in danger. They didn’t realize they had 4,000 people behind them. They weren’t concerned about people around them. And something about that disconnection lit a fire. I went into a rant about Paris, about our freedoms, about our sense of community, about sacred space, performance space, rituals, and how this is all going to be gone at some point. And this is the start of that. The moment. The disconnection. The constant need to be in front of your cellphone, which breaks the spell of live performances. We all need to be present. I’m finding these shows we’re doing now are so intense, and the new material demands so much from me in terms of being present as a performer. That discipline really came through to me working with Ray Manzarek and Robbie Krieger. Because i had to be 1000% present when I was working with them. I had to be at my very very best. I had an obligation not only to those guys, but to the audience and to that legacy. That really reconfirmed to me the importance of responsibility as a performer when you go out there. It’s not just entertainment.

You don’t have a Grammy. You’re not in the Rock and Roll Hall of Fame. Do you feel disrespected?

The only award we got of any significance was at the CMJ Awards in 1985 or ’86. It was at the Apollo Theatre in New York. It was for song of the year for She Sells Sanctuary. And Yoko Ono got up to present it to us and she made a speech about John Lennon and young songwriters directed at us. That moment was transcendent. There wasn’t really much that could top that. But already, at that point, we knew we weren’t going to go the straight route. Even though we had commercial success around Sonic Temple and were on MTV and all that nonsense, that wasn’t our path. We knew even then we were going to go the difficult route. It was going to be longer and deeper, with many more obstacles, but we were going to be here for the long haul. And here we are. But that’s just The Cult. We don’t concern ourselves with legacy or anything like that. We don’t roll into town with that sense of entitlement or expectation. Recently we played with Guns N’ Roses in Mexico City in front of an audience of 65,000 people for two nights. and the most profound moment was when we played Deeply Ordered Chaos in a lightning storm, with the rain coming down and drenching the audience and it was just beautiful. It was a stunning moment. It was an amazing moment. If anything, that’s what I take away from it. Those moments and those experiences, they’re profound.