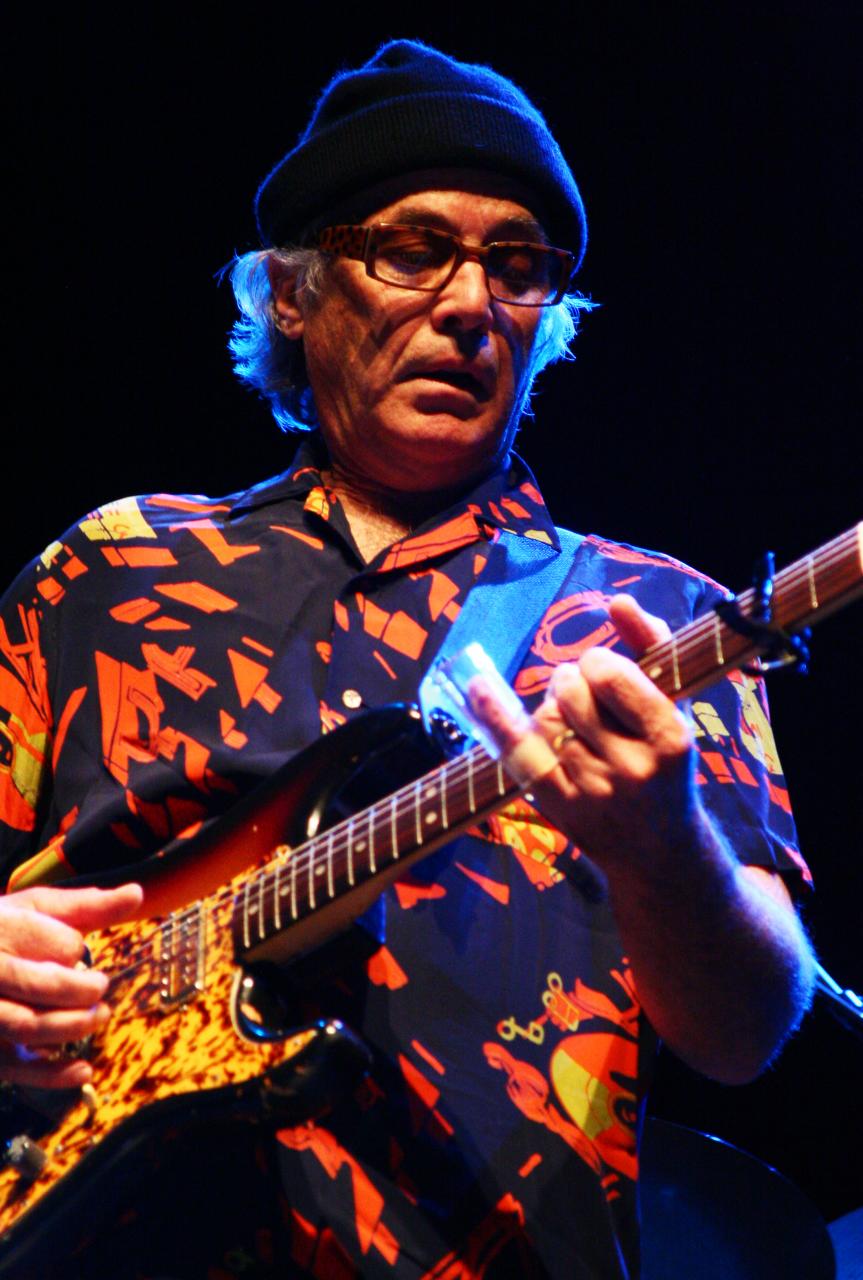

One of my favourite guitarists, the inimitable Ry Cooder, will celebrate his 72nd birthday on Friday, March 15. I was lucky enough to interview him about eight years ago for his then-current album Pull Up Some Dust And Sit Down, and was thrilled to find that he still had plenty of fire in his belly. Like most print interviews I did, much of what he said had to be edited out for space. Since I obviously don’t have that problem here, I’ve restored most of those long-lost quotes below. Enjoy. And happy birthday Ry.

It feels like old times to Ry Cooder. And that’s the problem.

Economic malaise, unfettered greed, spiralling unemployment, self-serving politicians, impotent media: Life in America hasn’t been this depressing since … well, the Great Depression, the veteran singer-guitarist and musicologist believes.

“It’s only perfectly obvious,” grumbles the ornery Cooder from his Santa Monica home. “I read history books. I know what this is all about. I’m not stupid. What we have now is a replica of those conditions. Politicians in general and corporations have manipulated and wrecked the country. As a nation, we’ve come full circle entirely.”

Fittingly, so has he. Cooder’s album Pull Up Some Dust and Sit Down harkens back to his ’70s heyday, when he specialized in unearthing and revamping Depression-era fare like How Can a Poor Man Stand Such Times and Live? and The Very Thing That Makes You Rich (Makes Me Poor). This time around, however, Cooder’s timeless tracks — a musical melting pot of folk, blues, country, Tex-Mex, gospel, soul and more — are topped with his own topical lyrics about everyone from bankers and brokers to illegal aliens and John Lee Hooker. It may be the most personal and potent album of his career; no small feat for a guy whose resumé includes more than a dozen acclaimed solo albums, a slew of magnificent Hollywood soundtracks and collaborations with everyone from The Rolling Stones and Captain Beefheart to Buena Vista Social Club.

Fittingly, so has he. Cooder’s album Pull Up Some Dust and Sit Down harkens back to his ’70s heyday, when he specialized in unearthing and revamping Depression-era fare like How Can a Poor Man Stand Such Times and Live? and The Very Thing That Makes You Rich (Makes Me Poor). This time around, however, Cooder’s timeless tracks — a musical melting pot of folk, blues, country, Tex-Mex, gospel, soul and more — are topped with his own topical lyrics about everyone from bankers and brokers to illegal aliens and John Lee Hooker. It may be the most personal and potent album of his career; no small feat for a guy whose resumé includes more than a dozen acclaimed solo albums, a slew of magnificent Hollywood soundtracks and collaborations with everyone from The Rolling Stones and Captain Beefheart to Buena Vista Social Club.

With Pull Up Some Dust in stores, Cooder made some time to talk about creeping up on Woody, the kids and their texting, and how he soothes his jangled nerves.

Most artists go from angry young man to aging gracefully. You’re getting feistier.

Ha! Not really. But I see what you mean. When you’re surrounded by all these criminal acts and this terrible devolution of political life and social structure here in America — I don’t how it must seem up there, but down here, at my age, you can certainly trace this arc of collapse and chaos — what are you going to do? It was either die of frustration and bitterness or make something out of it, you see. It’s bad mental health to let that overtake you.

But you came up in the ’70s during Watergate and Vietnam, and didn’t write about them. What’s different?

It took me a long time to get to where I had a handle on songwriting. You know, the old populist music of the ’30s, which was invented and written by working-class people, was used to describe their lives and what they were going through, whether you were on strike at the cotton mill or westward-bound on the road. But since I didn’t migrate west with the Dust Bowl guys like Woody Guthrie or see this first hand, I had to creep up on it more. It took time to absorb that kind of songwriting. It’s taken me … well, a lifetime.

You didn’t feel you had the skills back then?

I don’t know what I felt. All I know is that it wasn’t there. Now I can play the instruments the way I would like to hear them played. That didn’t happen overnight. I had a certain amount of dexterity when I was young that enabled me to start to play. But it took time. The same thing goes for the mental process. What really helped me with the songwriting is that I started to write short stories when I was doing the Buddy album. That was like an exercise in seeing where the story was and how to get at it. You need a four-minute song, so you better get at it somehow. So many times protest songs are … well, whatever they are, it’s not my style. So I had to find it and get a handle on it and finally I did.

Does it rankle you that protest music seems dead?

Well, here’s the thing: In the ’70s, you had one huge difference, and that was the record business. You had the three Rs: Radio, records and retail. You had a quick-response system. You could write a song and could go into a studio — in those days, you still did that too — and the record company could put it out as a single pretty quickly. So it was visible. And pepole heard it on the radio, which was very important — in fact, critical. You heard one of those Crosby, Stills and Nash tunes and you would say, ‘Yeah, i just heard about that.’

You could do that today on the Internet.

Oh, I don’t think it’s the same. The internet is so vast and so diffuse. You can’t compare that to the record business and the way it worked. And digital cyberspace doesn’t provide a shared experience. I used to go see Pete Seeger, and within minutes he’d have an entire audience singing. When people sing together, they feel the same thing, they feel kinship. And by the end of the song, they’ve learned something and they can be moved forward. It’s hard to have this kind of experience now; that feeling of solidarity.

Speaking of performing, you haven’t done much lately. Why not?

It’s hard. I’m a homebody. Travelling was not my favourite thing. And it’s very difficult to do music out in the world. It’s the most random, odd feeling. But I’m starting to think people are ready for this message. I don’t know about the youth with their texting; they’re hypnotized by their little screens. But they don’t come see me anyway unless their grandparents bring ’em. But I think older people will respond to this. So if that means I go and play for 150 people — which I think is an ideal audience — to get this message across and give them the feeling I want them to have, I’m happy to do it. We’re going to try a couple of shows this month. We’ll see if I can pull it off. If it’s motivating, maybe I’ll find a friendly billionaire who will underwrite the whole thing.

You’ve collaborated with so many great artists. Who’s still on your wish list?

I don’t know about that. Those things were never planned. They were just phone calls away. Obviously the big call was for Buena Vista Social Club: ‘Would you like to come to Cuba?’ And that’s why I’m still here. Without Buena Vista, I couldn’t afford to live here anymore. The truth is, nothing ever worked very well financially for me. But I didn’t have to worry because we’ve been living in this house for 38 years and we didn’t pay very much for it when we got it. And life was fine. But suddenly, I thought, ‘My God, we’re making some pretty good money here.’ It was nice to see. We put some money in the bank and put some money by for our old age, so I’m not worried any more even though it’s crashing all around us.

I find it reassuring that your music has retained its own sound. You’ve never chased a trend.

Heaven forbid. I wouldn’t even know a trend to chase. heaven forbid. I think it was Dizzy Gillespie who said, ‘You never finish learning your instrument.’ And it’s a wonderful idea because then of course life is always unfolding. You think you’re getting better, and you’re supposed to. And this increases your knowledge of everything, and you sense increases, and therefore you sound better. I like the idea, anyway. The instruments are nice. They’re like friends. You pick ’em up and play and it feels good.

What kind of music do you listen to?

Classical. It’s very spacious and undemanding, especially the French guys. I like Ravel and all those cats. It’s very soothing to my jangled nerves.