“Isn’t there anyone who knows what Thanksgiving is all about?”

– Charlie Brown

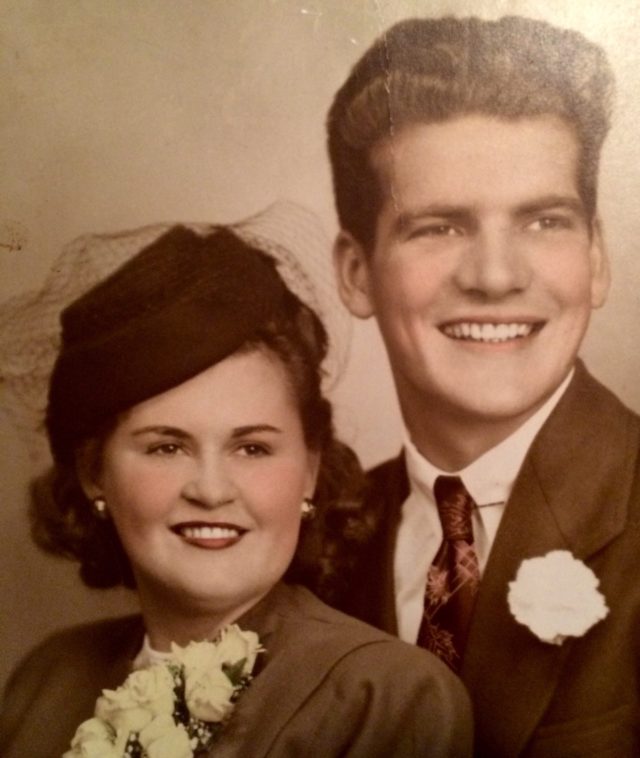

Mom-Mom was pudgy, jittery, and kind. On her one hand she had a ring made of a spoon handle. It was carefully twisted in a way that seemed almost otherworldly to my kid eyes, like if tornado took a flag pole and wrapped it around a tree like a snake. Her life was all but a mystery to me even though I didn’t know that then. I knew that her and Pop-Pop had been married forever. And I knew that they loved each other, or had to, I supposed, although the reasons why were never quite clear to me. Obligation probably played a part. In the old days people stayed married long after the romance had collapsed and rotted away right there on the living room floor. Couples and their children, really anyone who came into the house, would all step over the dried carcass. Then the raw bones. Then the dust, I guess, if anyone survived that long.

Mom-Mom was pudgy, jittery, and kind. On her one hand she had a ring made of a spoon handle. It was carefully twisted in a way that seemed almost otherworldly to my kid eyes, like if tornado took a flag pole and wrapped it around a tree like a snake. Her life was all but a mystery to me even though I didn’t know that then. I knew that her and Pop-Pop had been married forever. And I knew that they loved each other, or had to, I supposed, although the reasons why were never quite clear to me. Obligation probably played a part. In the old days people stayed married long after the romance had collapsed and rotted away right there on the living room floor. Couples and their children, really anyone who came into the house, would all step over the dried carcass. Then the raw bones. Then the dust, I guess, if anyone survived that long.

I was never sure if my grandparents (my mom’s people) were happy. It was difficult to say. There was no overt joy, no daily spark or gleam in their eyes. Neither one of them retired really. Mom-Mom worked in a soulless bulk mailing warehouse across the river from our town until she died of breast cancer in her 60s. Pop-Pop fell dancing at a wedding and broke his leg when I was pretty young and he was still in his 50s. Before that he’d been in construction but he never worked again as far as I can tell. The ebb and flow of their days and nights was not knowable to me. I was on the block, around the corner when my parents were married. Then by the time I was 8 or 9, I was in my grandparents’ home, just down the hall in a spare bedroom. But even then I never understood the chemistry of their union. No kid could have.

All I knew was that I loved them and they loved me. The possible suffering within each of them never resonated with me. I suppose I couldn’t see the forest for the trees, as they say. Now that I’m older, more beat up by the world, I can understand things better. Beyond the harsh language Pop-Pop routinely aimed at Mom-Mom there must have been some extraordinary discontent. Behind the frustrated sighs I’d catch Mom-Mom making, there were likely gaping emotional wounds gushing blood that she never let anyone know about.

Sometimes I would walk in on her doing the dishes and crying. Then she’d immediately try to cancel out the entire world for me, protect me with her loving smile and a can of soda straight out of the fridge.

They were working class, whatever that means. They were both Navy vets of World War II and neither had ever gone to college or probably even thought about it. Their era was wildly different than this present you and me are seeing. People worked at industrial jobs and service jobs and they used their hands to make things or fix stuff. The jobs were there, I suppose. Not far from their house. You could probably walk to a lot of the work available to you back in the 1940s and the 1950s. But ultimately the world began to change in front of them just like it’s been changing in front of us. Just like it changes in front of everyone who lives past the age of 50 or so, I’d say.

Politics make hard jabs in this direction or that one.

Countries destroy each other.

Music styles come and go and all the while it always seems to the people living through it that the way things are right then and there, they’ll probably stay that way for a long time.

It’s quite difficult to imagine your favorite bands being buried and forgotten beneath the rockslides of time. It’s almost impossible to think that someday before long the country as we know it will be utterly gone. New flags will fly in time. Fresh takes on sexuality and violence and self-medication will rise up from a landscape where these new ideas once seemed unspeakable, let alone possible. And Mom-Moms and Pop-Pops will wake up in the morning/ perhaps: as history sometimes repeats itself: in separate beds once again/ and they’ll lie there/ right before the alarm sounds/ their breaths coming long and easy/ before the coming day will take what it will take from them/ and they will each watch the ceiling, so bluish, like dead skin/ as they try to wrap their tired heads around something incidental and unimportant in the grand scheme of things. But something they can’t ignore all the same.

False teeth in a glass on his nightstand. Pop-Pop would rip a fart that could kill a squirrel.

Down the hall, Mom-Mom would hear it like a growling from inside the walls.

Downstairs the fridge hummed like an engine in a plane flying low through this fog that goes on and on and on until a mountain comes out of nowhere and, just like that, it’s done.

At Thanksgiving I would watch Pop-Pop. I don’t know why. He seemed to play his character more sharply and with better intensity on these holiday stages than at any other time. He’d wear one of his better polo shirts. Maybe the light blue one with the Conshohocken VFW logo on his right tit. And he’d be drinking early. A can of beer at 10 a.m. was not unusual or commented upon. The day was festively tinged and for drinkers in the old days that meant a free pass to make up the rules as you go. A crystal dish of cheese cubes and fancy nuts was enough to raise a man’s spirits to another level, you see. As a result, there often came to the surface certain elements of his deeper consciousness that he rarely allowed himself to entertain the rest of the year. Within the alcoholic mind at the holidays, there were snowy countrysides and sleigh rides and silent peaceful evenings that stretched forward in front of them. Down the main drag/ the streetlights brimming with a barrage of illuminated flakes falling so delicately from the slate dark of low space. Down, down, down to these neighborhood streets humming with the radicalized energy of a holy excuse to remove one’s self from the grim-ish reality of daily life/ and to supplant one’s unfathomable and unknowable blues with the mawkish ethos of a era in which a couple of bottles of gift liquor were meant to be finished amongst friends. Amongst friends in a fit of festive merriment. Among family in a rage of gay old joy.

Mom-Mom was different than him. She was more grounded, acutely tuned into the cruel world surrounding her with kind eyes and weapons of heart. If meanness could kill a person then Mom-Mom would have been laid out not so long after I was born. By the mid-1970s Pop-Pop had begun a descent into drinking that he wouldn’t fall away from until the end of his life, when he was holed up in a temporary room in some nice enough place where people wait to die. Until then he had drank his fill though. That combined with whatever unmoored emotions had begun floating around within him long ago brought him to the place of many men he’d call his peers. Shipped off to war, brought home to a swinging party, they slipped back into the world differently than the World War I guys did before them and the Vietnam guys did later on. Their homecoming, for the white GIs anyway, was all confetti and warm slaps on the back. I have no idea what that does to a person. Maybe it made a lot of them feel like they’d saved the world from tyranny. Maybe it made some of them feel like they’d found a purpose in life. And maybe, for at least a few, Uncle Sam dropped them off downtown and they got lost behind the bus station. And they never got found again.

Dramatics aside, Pop-Pop, by the time I knew him, was wonderfully kind to me and openly horrible to Mom-Mom.

I remember times he’d be cursing her for not salting the green beans enough or something ridiculous like that. Immediately upon his words/ right in front of me and my brother and my mom at the Sunday dinner table/ I would notice the color slipping out of her skin. Where the soft welcoming pinks had been now there was only this fragile white. Her silence felt strong but her slumped shoulders and under-her-breath apologies to Pop-Pop reeked of a weakness I couldn’t get behind or even identify. It was as if the man had the power to control her. And that was likely because he, in fact, did have just that. With a slosh of his white bread through the muddy beef gravy, he could make her nervous/ insecure/ shaken deeply with a fear of what might come next. Because often it was reproach, presented bitterly and succinctly by a Pop-Pop who had many broken things inside of him. None of which I know about or even pretend to understand.

But broken people need to break other people.

And so that’s how all this went.

To read the rest of this essay and more from Serge Bielanko, subscribe to his Substack feed HERE.

• • •

Serge Bielanko lives in small-town Pennsylvania with an amazing wife who’s out of his league and a passel of exceptional kids who still love him even when he’s a lot. Every week, he shares his thoughts on life, relationships, parenting, baseball, music, mental health, the Civil War and whatever else is rattling around his noggin.