It was Halloween night, and the streets of Winnipeg were empty. Empty, that is, except for me. I was looking for Veda.

It was Halloween night, and the streets of Winnipeg were empty. Empty, that is, except for me. I was looking for Veda.

I’d heard there was only one way to find her. It had to be All Hallow’s Eve, nearing the witching hour; and – and this was the difficult part for me – one couldn’t be looking for her. Which I was.

I saw a sinister-looking man standing on a corner, the streetlight conspicuously bathed him in a faded purple glow.

“How do I find Veda?” I asked him.

“No one finds Veda,” he said, and I saw that he had no eyes. “Veda finds you.”

“I’d like Veda to find me,” I said.

He turned his face toward mine, as if staring at me, looking me over.

“What is it you wish to ask the great Veda?” His voice had changed; the raspy, smoke-damaged whisper was replaced by a woman’s voice: Veda’s.

“No doubt it is the same that many others have asked you, Veda. I wish to know the future. What is my fate? And how can I avoid it?”

“Have you the ingredients?”

My hand went to my pocket. Yes, I had them.

A door swung open – a door I had not noticed was there – and behind it I saw nothing but darkness. The eyeless man stood aside, and I walked through its threshold. A feeling of being nowhere and everywhere welled up inside me. The world was both small and infinitely expansive. I could make little sense of it, and so I continued forward. Nausea turned my stomach over upon itself.

Slowly, the light returned, and it was the same purple glow that permeated the streets. But now it fell on a stack of wooden crates, bookshelves and trinkets, on the severed heads of rats and chickens, on bats’ wings and lizard tails, on vials, on potions, on poisons and antidotes, on scrolls and spells – all scattered throughout the room with a chaotic order. And, then, there in the middle of it all, resting on chair of what looked like human bones, was Veda. Her eyes thoroughly pierced me; my soul (my being) stood naked before her.

I handed her the ingredients: a bloody Kleenex and the knife that caused the blood, the tongue of a duck, and three rock-tumbled and polished kidney stones.

Each Veda dropped into a small cauldron that rested between her thighs. Noxious fumes spewed out, a hidden heat-source frothed the liquid, bubbles boiled, hissed.

Veda closed her eyes, and she leaned forward, put her face against the cauldron’s mouth, and breathed in. When she sat back, I saw her eyes had turned a luminous green, and they darted around, not quite fearful, but as if they were seeing ghostly spirits fill the small room.

“I will only ask you once. Do you really wish to know your fate?” I noticed a caution in her voice, as if she was giving me one last out, one last chance to remain happily ignorant.

• • •

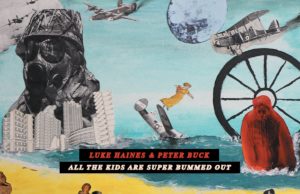

To read the rest of this review — and more by Steve Schmolaris — visit his website Bad Gardening Advice.

• • •

Steve Schmolaris is the founder of the Schmolaris Prize, “the most prestigious prize in all of Manitoba,” which he first awarded in 1977. Each year, he awards the prize to the best album of the year. He does not have a profession but, having come from money (his father, “the Millionaire of East Schmelkirk,” left him his fortune when he died in 1977), Steve is a patron of the arts. Inspired by the exquisite detail of a holotype, the collective intelligence of slime mold, the natural world and the suffering inherent within it — and also music (fuck, he loves music!) — Steve has long been writing reviews of Winnipeg artists’ songs and albums at his website Bad Gardening Advice, leading to the publication of a book of the same name.