There’s a lot of heartbreak in rock ’n’ roll. Few bands are democracies and fewer still are charitable. Popular music is rife with ego, pride, desperation and paranoia. Somewhere, right now, a great musician or a great person is probably getting cut out, shortchanged, overlooked or left behind by a band on the rise.

There’s a lot of heartbreak in rock ’n’ roll. Few bands are democracies and fewer still are charitable. Popular music is rife with ego, pride, desperation and paranoia. Somewhere, right now, a great musician or a great person is probably getting cut out, shortchanged, overlooked or left behind by a band on the rise.

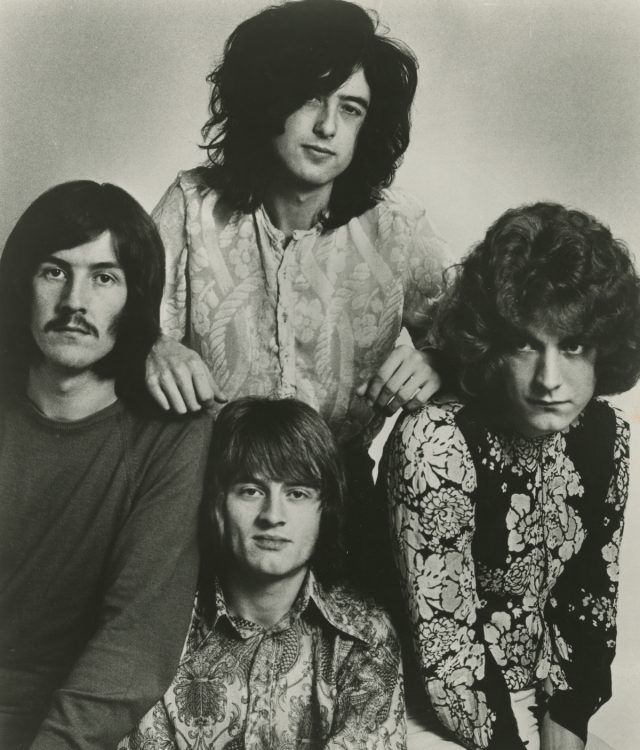

I was reading Bob Spitz’s 2021 biography of Led Zeppelin, in which — among hundreds of other things — he details the way in which producer Glyn Johns seemingly got screwed out of a co-producer credit and royalties on the band’s debut album. Initially, Johns was to be listed as the album’s co-producer, but just prior to release, Jimmy Page reconsidered this and listed himself as producer and Johns as “director of engineering.”

The two men had clashed throughout the recording. At the end of the day, Page believed it was he who put the band together, arranged all the songs, developed his own guitar sound and was present throughout recording. Page instructed Johns on how to do a reverse echo and insisted on close-mic techniques. He concluded he could — and did — overrule anything Johns decided, meaning he, rather than Johns, was the album’s producer. Certainly it was Jimmy’s baby, his concept and his cash making it all happen. So he directed Zeppelin manager Peter Grant to inform Johns that he would not be listed as the album’s producer.

From Johns’ perspective, he poured himself into the project, believed in it, and developed his system for recording stereo drums during the sessions. The record does sound astonishing. But maybe what each person did or didn’t do isn’t really what matters. What matters is that Johns was hired as producer and an agreement was reached involving a share of the album’s royalties. Instead, as engineer, he simply received payment for the work completed.

The incident is something which gets less of a mention in Johns’ own 2014 book, even though the band is listed in the title (Sound Man: A Life Recording Hits With The Rolling Stones, The Who, Led Zeppelin, The Eagles, Eric Clapton, The Faces…). On a less diplomatic note, Spitz’s book suggests Johns called Grant a “cunt” after the demotion and vowed never to work with the band again. He never did, and wasn’t invited to.

If Johns had received a producer or co-producer credit, and the royalty share he was initially promised, it would have been hugely lucrative. Commonly, producers get between 1% and 5% of the recording’s earnings. Led Zeppelin’s debut has sold nearly 16 million copies — plus the equivalent of nearly 800,000 albums in digital downloads. From what I’ve seen, the recording cost £1,782 — and that includes George Hardie’s album cover artwork. Presumably, Johns’ engineering fee was included in that sum. That’s the equivalent of £25,000 today, or $45,000 CAD. That leaves a lot of room for profit.

Page wasn’t the only rocker Johns clashed with over the years. The producer was known not to mince words. He was excused from the recording of Wings’ Red Rose Speedway because he accused the band of writing underwhelming songs, getting stoned and wasting tape — and his energy. He considered Rod Stewart nothing more than “the singer” of The Faces and was upset that Ronnie Wood joined The Rolling Stones, where he believed he was little more than “a mascot.” He was even more blunt about Wood’s predecessor Mick Taylor. During the Exile On Main St. sessions, he essentially told Mick Jagger ‘Either he goes or I go.’ Johns was also canned by the Eagles for not allowing drugs in the studio and being generally unsupportive of their move towards a more rock-oriented sound. So who knows how much cash he missed out on by not keeping his trap shut.

That first Led Zeppelin album had a host of other royalty ripoffs associated with it — mostly of the songwriting variety. While Page was still a member of The Yardbirds, the band played a gig with American folkie Jake Holmes. After searching various listings and databases, I believe it took place on Aug. 25, 1967 at New York’s Village Theatre — incidentally, one day before The Yardbirds played Hidden Valley Ski Resort in Huntsville, Ont. At the former show, Page reportedly saw Holmes perform his song Dazed And Confused, and was quite taken with it — particularly how the vocal lines floated over the musical progression.

Page reworked the song, and Yardbirds vocalist Keith Relf rejigged the lyrics. By March 1968, their version was a regular feature in The Yardbirds’ set, and now is the seventh most-played song by the band ever. It is the most-played song by Led Zeppelin, whose debut album gives songwriting credit solely to Page.

Holmes tried to contact the band over the years about getting credit for the song, but it wasn’t until 2010 that he finally sued Page over it. The matter was “dismissed with prejudice” in 2012. But there must have been some sort of out-of-court settlement, because when the Celebration Day reunion album and video came out in 2012, Dazed And Confused was credited differently for the first time — “Jimmy Page, inspired by Jake Holmes.” Clearly, he got some cash — but probably nowhere near what he could have had if his name had been on the track since 1969. Interestingly, Page has said Robert Plant is responsible for the lyrics, even though he also has no songwriting credit. We’ll assume the pair have worked that out amongst themselves.

There were other liberties taken on the album. The band essentially set out to cover Joan Baez when they recorded Babe I’m Gonna Leave You. Baez had released it in 1962 on her In Concert album — mistakenly credited as “Traditional, arr. by Baez,” even though it had been written by folk singer Anne Bredon. When Led Zeppelin released it, they — like Baez — listed it as “Traditional, arr by Page.” It stayed this way until 1990, when Bredon reached out to Page. The credit now reads Bredon-Page-Plant, so she likely gets royalties.

If you’re wondering what kind of money we’re talking about, royalties for bands like this can be astronomical. Let’s look at one example. On New Year’s Day 1962, The Beatles auditioned for Decca Records. The label made the legendary mistake of passing on them. Their 15-song audition was recorded, but remained unreleased (at least officially) until the surviving Beatles decided to include five of those songs — Searchin’, Three Cool Cats, The Sheik of Araby, Like Dreamers Do and Hello Little Girl — in 1995’s Anthology 1. It was the first time The Beatles released a song with Pete Best on drums. Suddenly, Best found himself sitting on around $9 million in royalties.

Now, back to that Zeppelin debut — and its killer closing track. How Many More Times is one of the first songs I learned to play as a teenage bassist, along with KISS’s Firehouse and Black Sabbath’s Hand Of Doom. The song is something of a medley — much of the middle is the same as a song called The Hunter by Carl Wells and members of Stax Records’ house band Booker T. & The M.G.’s., who recorded it with bluesman Albert King in 1967. He released it as a single in 1969 — the same year Ike & Tina Turner released their version. U.K. band Free also included a version on their 1969 debut album Tons Of Sobs. All these versions credited “Jones-Wells-Jackson-Dunn-Cropper” — the members of Booker T. & The M.G.’s. But Led Zeppelin’s How Many More Times credits “Page-Bonham-Jones.” Eventually, Plant’s name was added to the credit, as it was with Babe I’m Gonna Leave You. And The Hunter isn’t the only song they apparently borrowed on this track. It also sounds suspiciously like Howlin’ Wolf’s How Many More Years.

These incidents continued on Led Zeppelin II. The monster opening track Whole Lotta Love was the band’s first hit. It draws heavily on a track called You Need Love, recorded by Muddy Waters in 1962 and written by Willie Dixon. But Whole Lotta Love was credited to “Jimmy Page, Robert Plant, John Paul Jones and John Bonham” until 1985, when Dixon sued and settled out of court for a co-writing credit and a lump-sum payment. The credit now reads “Page-Plant-Jones-Bonham-Dixon.”

While Howlin’ Wolf (Chester Burnett) didn’t get a songwriting credit on How Many More Times, he did eventually get one for The Lemon Song. The famous third track on Led Zeppelin II is basically Killing Floor, written by Burnett in 1964. Jimi Hendrix performed it often, including — famously — at the Monterey Pop Festival in 1967. Led Zeppelin also played Killing Floor, and merged it with parts of Robert Johnson’s Travelling Riverside Blues (where the “squeeze my lemon” lyrics originate) and King’s Cross Cut Saw (where Plant changed “drag me cross your log” to “juice runs down my leg”).

The blending of the three songs led Zeppelin (pun intended) to rename it The Lemon Song when they recorded it in 1969. Burnett got his credit after U.S. publisher Arc Music sued the band in 1972. Another out-of-court settlement earned Burnett a cheque for $45,000 US, and ever since the songwriting credit on The Lemon Song has read “Page-Plant-Jones-Bonham-Burnett.”

• • •

Area Resident is an Ottawa-based journalist, recording artist, music collector and re-seller. Hear (and buy) his music on Bandcamp, email him HERE, follow him on Instagram and check him out on Discogs.