As a frequent peruser of thrift-shop record stacks, I can say with some degree of certainty that the addition of Hawaii as the 50th state on Aug. 21, 1959 had a huge influence on popular music.

As a frequent peruser of thrift-shop record stacks, I can say with some degree of certainty that the addition of Hawaii as the 50th state on Aug. 21, 1959 had a huge influence on popular music.

Hawaii had been annexed by the U.S. in 1898 after its monarchy was overthrown by American and European businessmen five years earlier. It had spent the previous 83 years as an independent, globally recognized kingdom. Before that, it was the wild west of exploration, trading and whaling by Europeans and Americans, whose ailments and diseases decimated the population which had been around 500,000 when British explorer John Cook first arrived in 1778 — and around 40,000 at the time of annexation.

Tragic and awful, leading the U.S. to officially apologize in 1993 for overthrowing the monarchy. But to date, there’s been no apology for the onslaught of kitschy, derivative music which became all the rage in North America for more than a decade after being forced into the union.

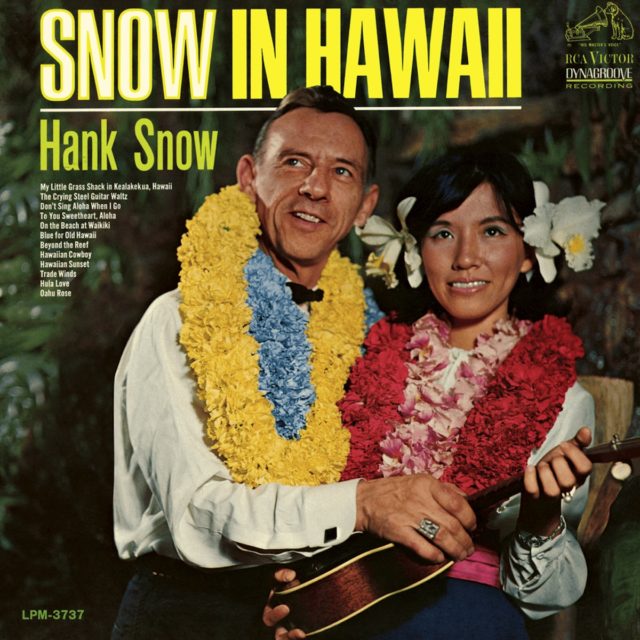

Never mind the films and TV shows like Hawaii Five-O, Blue Hawaii and Fantasy Island. We’re going to focus solely on music. This after I recently acquired the horrendous 1967 LP Snow In Hawaii by Canadian country hall of famer Hank Snow. I guess he needed to add another verse to I’ve Been Everywhere.

This miserable album can be found smack dab in the middle of the Nova Scotia-born Snow’s catalog of nearly 50 studio albums. Between 1952 and 1979, he did multiple tribute albums, religious and gospel albums, spoken-word albums, Christmas albums, a Yukon album, an instrumental album and this ridiculous Hawaii album where he sought to cash-in on the Polynesian craze. The cover photo features him, with fancy cuff links, a huge ring and his paws around a young Hawaiian woman — who, like him, is wearing multiple leis and looking wearily off-camera.

Don’t confuse this post-statehood craze period (1960-1975) with the “second Hawaiian renaissance” that took place starting around 1970, and focused on Hawaiians revelling in their culture. The first Hawaiian renaissance happened during the rule of King Kamehameha V in the 1880s, when Hawaii was an independent nation. The second was inspired by a 1964 essay by John Dominis Holt called On Being Hawaiian. It dealt head-on with the type of stereotypical tripe we find on Snow’s LP, which I find unlistenable.

Old country, mixed with stereotypical Hawaiian sounds and themes. Songs like Hula Love, My Little Grass Shack in Kealakekua and Hawaiian Cowboy. Even sadder, the country/exotica album nobody asked for was recorded in Nashville and produced by Chet Atkins — who never did a Hawaiian album, but certainly did loads of Hawaiian-themed songs. Atkins cut two tracks of slack-key guitar (a Hawaiian style of open-tuned finger-picking) and a well-known rendition of Hawaiian Wedding Song.

Don’t get me wrong. I love my kitschy Hawaiian records. But there’s a line. For example, one of my favourites in my collection is a record called Hawaiian Moonbeams. Nobody is 100% certain who the artist is because it has been re-released and repackaged so many times. One version is even, bizarrely, entitled Hawaii Goes Percussion. It’s bizarre because there are absolutely no drums or percussion on it at all. The record is typically credited to the mysterious duo dubbed Hawaiian Moonbeams, and is considered a rare and desirable exotica artifact. It is sometimes characterized as a “hapa haole” album — a term which basically means multi-racial. In this case, white and Hawaiian. It is a legit, self-celebrating Hawaiian renaissance recording, with mass-marketing by the less respectable craze which started when Hawaii became a state.

So who, apart from Hank Snow, got in on the Hawaii craze? Well, Elvis Presley was an early devotee. He famously did films in Hawaii with popular soundtracks — Blue Hawaii (1961), Girls Girls Girls (1962) and Paradise, Hawaiian Style (1966). He also did the Aloha From Hawaii via Satellite live album and TV special in 1973. Paradise, Hawaiian Style was largely filmed at the Paramount studios in Hollywood, where Elvis first met British belter Tom Jones. The two were friends until the King’s death on Aug. 16, 1977.

After Elvis left the building for good, Pickwick Records put out a compilation called Mahalo From Elvis, which featured one side of tracks recorded after the Aloha From Hawaii concert in 1973 with no audience present. The other side compiled tracks from his films.

Jones, for his part, now co-owns three Japanese restaurants in Hawaii. While he never made a Hawaiian album, he has said the first song he ever remembers having an impact on him was Tommy Dorsey’s Hawaiian War Chant from 1938. It’s an old song, written by Prince Leleiohoku in the 1860s. My father also loved it.

In 1967, The Beach Boys did a tour of Europe in May, and then pulled out of their planned mid-June appearance at the Monterey Pop Festival — opting instead to do two shows in Honolulu on Aug. 25 and 26. The idea was to release the material as a live album, regretfully to be called Lei’d in Hawaii. Even Brian Wilson managed to make the trip, appearing with the band on what would be the only occasion between 1965 and 1970. But they weren’t very well-rehearsed and at least two of them were on acid. They didn’t do so well, and in the end it was decided to record the live album in the studio. It was never issued officially, until suddenly both the live and studio recordings were released in 2017 on the compilations 1967 Sunshine Tomorrow 1 and 2.

In 1987, Dolly Parton opened a restaurant in Honolulu called Dolly’s Dockside Plantation. Reviews were bad. “Terrible” is the description I read in Midweek. It wasn’t long before the name was changed to DP’s Dockside Plantation… and then a new sign which read “for lease.” That same decade, Dolly had a variety TV series called — you guessed it — Dolly. It often featured Hawaii, including an episode called My Hawaii. If I thought Snow’s brand of country was misplaced, I wasn’t prepared for this:

Dolly recorded a number of ’80s songs with Hawaiian entertainers and even bought a plantation-style beachfront home on Portlock Beach, outside Honolulu. It was extensively remodelled, and eventually sold. You can rent it by the week. This year she teamed up with Felix Cavaliere, the former vocalist and keyboardist of The Young Rascals/The Rascals, to re-record the band’s 1968 track My Hawaii. The new version was used as a fundraiser for the survivors of the Maui fires.

While this is a fantastic idea, it strikes me as odd that The Rascals would have recorded such a song in ’66. Cavaliere wrote it, and he’s from Fulham, N.Y. He lives in Nashville. He’s never lived in Hawaii. Holy fuck, is this awful.

Willie Nelson certainly has — and does — live there. His home was one of those spared during the Maui fires. Willie is not the only well-known musician who has, at least at one time, had a home in the Aloha State. Others include Paul Simon, Steven Tyler, Neil Young, Mick Fleetwood, Kris Kristofferson, Sammy Hagar, Jack Johnson and Gene Simmons.

I think you could probably hurt yourself laughing if you mixed the right kind of weed or mushrooms with a listening session of a so-called Hawaiian Christmas album. These things were all the rage. If you search “Hawaiian Christmas” on Discogs, you get a list of nearly 700 albums that fit this description. I mean, I’d certainly buy Santa Goes Hawaiian.

We’ve all heard Bing Crosby or The Andrews Sisters’ versions of the classic Mele Kalikimaka, but have you heard Davy Jones of The Monkees‘ take on this Hawaiian Xmas classic from 2005? (At least 30 years too late.)

During the ’60s and ’70s, when all-things-Hawaiian were trendy, there were plenty of acts who tried to pass themselves off as Hawaiian. The Waikikis, for example. The Belgian studio band made a dozen albums between 1963 and 1969. Their song (and album) Hawaiian Tattoo was a huge hit in 1961 in Europe and Canada, but lesser so when it was released in the U.S. in 1964. To Americans and Canadians of a certain vintage, however, their best-known song might be Hawaiian March, because of its inclusion in the 2004 film The Spongebob Squarepants Movie.

Incidentally, the theme music for the crime series Hawaii Five-O (1968-1980) was an instrumental by Morton Stevens, performed by studio musicians including Tommy Tedesco and Milt Holland of The Wrecking Crew, and Tom Scott and John Guerin of LA Express (Guerin also was The Byrds’ drummer for a few years). It wasn’t The Ventures who performed the theme, but they did cover it in 1969, and it was their biggest hit.

Don Ho was arguably the most famous act from Hawaii. The crooner was actually born there in 1930, though he was part Hawaiian, part Chinese, Dutch, Portuguese and German. Ho did part of his education in New England before finishing at the University of Hawaii. He then joined the U.S. Air Force in California and in the mid-’50s bought an electronic keyboard with some of his salary. He moved to Hawaii in 1959 to be with his ailing mother and soon launched his music career which saw him release dozens of albums including his biggest hit, Tiny Bubbles, in 1966. It was all perfectly timed with the Hawaiian craze and led to Ho appearing on I Dream of Jeannie, The Brady Bunch, Sanford and Son, Batman, Charlie’s Angels, McCloud and Fantasy Island. He even had his own weekday morning variety program on ABC from the fall of 1976 to March 1977.

But if you really want to get immersed in some thick Hawaiian kitsch, get your hands on a 2015 compilation by U.K. label Strut Records called Aloha Got Soul — a 16-track double album of Hwaiian-made disco and album-oriented rock from the late ’70s through the mid-’80s. You will never do anything in an unsexy way ever again.

• • •

Area Resident is an Ottawa-based journalist, recording artist, music collector and re-seller. Hear (and buy) his music on Bandcamp, email him HERE, follow him on Instagram and check him out on Discogs.