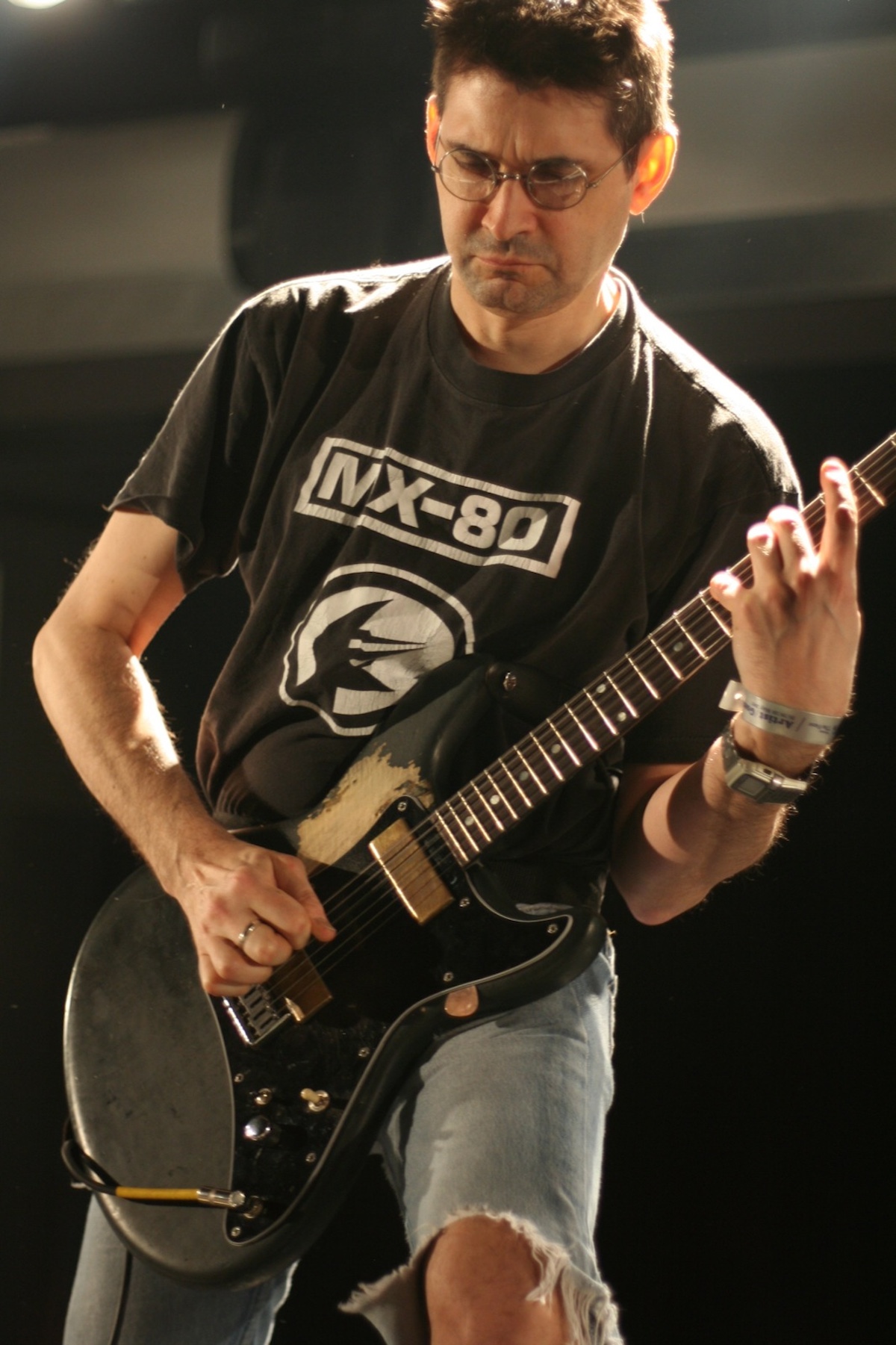

Like countless others, I was simultaneously surprised, shocked and saddened to see that Steve Albini died of a heart attack the other day. Surprised because he was only 61. Shocked because frankly, he seemed like a guy who was way too stubborn to submit to anything as lame and unoriginal as death. And saddened because he was a man who possessed integrity, honour and principle as well as talent and individuality. We need way more of those. Especially right now.

I had the privilege of chatting with the famously irascible musician, engineer and producer (a term he hated but nonetheless earned and personified) a couple of times. The first, if I remember correctly, was when he came to Winnipeg to produce local indie-rock gonzos Stagmummer back in 1997. The second was a couple of years later, when his band Shellac were touring Western Canada. I can’t find the first chat in my archives, which is a shame, because I recall it being a fairly feisty exchange. If I find it, I’ll post it. Meanwhile, here’s the full transcript of our second encounter, followed by the story that ran at the time. As always, Albini was candid, eloquent, opinionated, informative, self-aware and refreshingly, disarmingly honest. Enjoy.

Hi, Steve.

Hi. So how’s Canada?

Canada’s fine. But you know what it’s like up here, you’ve been here before. You were here to work on the Stagmummer album.

(Frontman Zack Walsh aka Jack Balles) actually was instrumental in helping us get a show there on this tour. Since we’re not a Canadian band, we don’t know about the touring scene in Western Canada. So we called up Zack the littlest punk, which I believe was the nickname he got when he was a little kid hanging around all the punk rock shows.

Do you remember any of your time up here producing their album? You’ve been involved in so many records, I would think after a while it would all become a blur.

The bummer is that you tend to forget things that are mildly disappointing — things that don’t really raise any interest even while you’re doing them. But the real catastrophes you remember and the real high points, of course, you remember, and then bits and pieces. It’s like anything else; I bet if you interviewed a baseball player, he would remember something about every game that he played, but he might not remember something about every inning that he played.

How many albums do you figure you’ve worked on at this point?

A couple of years ago I figured it out sort of statistically that it was over 1,000, so it’s probably up around 1,500 by now — 1,500 different records.

Is that everything from singles to albums and performing to producing?

Well, stuff that I personally have put out or been on as a band member, there’s probably a total of 75 or 80 releases. But actual albums, there’s only a few. There’s more singles and EPs and stuff like that. Albums are a pretty big deal to my way of thinking. You really only have any business putting out an album if it’s going to be a real good one. A lot of people throw albums out like hankies; some bands will spend an entire album on an idea that really warrants a verse.

Shellac haven’t put out anything since Terraform in 1998. Why are you touring at this point?

Our touring doesn’t really coincide with record releases in any sense. It never has, never will. We just figure out interesting places to go and we go there. We figure out interesting ways to tour and then that’s the methodology of the tour. This one is just Western Canada. We’re playing in Seattle at the beginning and then we’re playing in Duluth and Minneapolis once we drop down into the States, but the reason for the tour is just Western Canada.

Why here?

It seems like a part of the country I’d like. The Rockies are more dramatic the farther North you go. I like the idea of spending some time travelling through the Canadian Rockies. I grew up in Montana, so I really like the northwest just as a climate and a place to be. That time of year is a really nice time to be in the Rockies, so I’m looking forward to spending some time in the beautiful part of Canada instead of just going to Toronto and seeing the part of Canada that looks a lot like most of America.

It sounds like a paid vacation almost.

Almost all of our touring stuff is. In June we did a tour of the Netherlands, and Scandinavia and Iceland. It was outstanding; it was a really great trip. We got to spend time with people that we really like and see things that we never would have seen anyways; and along the way we got to play a few rock shows.

You’re so in demand as a producer and an engineer it would seem like a major disruption in your life to pack everything up and go on the road.

It is, but the band exists as something that is sort of a reward for us; being able to play together, being about to tour, being able to make records — those are the high points of my year. So if I have to work extra-hard for a little while in order to earn the free time that it takes to do stuff with the band, that doesn’t bother me at all. If it looks like I’m going to be gone for a little while, that means I have to do more stuff back-to-back than I might have otherwise.

I can’t imagine what working extra hard for you is.

I try to work every day. That’s sort of my rule of thumb. If there’s an open day on the calendar, then one way or another I’ll find something that I should do that day.

Doesn’t it become a grind at some point?

Anything could become a grind if you think of it that way. Occasionally, physically it’s fatiguing. But it’s stimulating work; I like all these people that I work with. I like everything that I do. I really enjoy working on great records, which happens once in a while.

What’s the last great record you worked on?

Hmm, let’s see … I really like the last Neurosis album that I did. I think that record came out really great. There are a lot of records that I’m satisfied with on one level or another, but it’s only four or five years later that you recognize the ones that were really great as opposed to the ones that were effortless or that were fun.

Do you have a personal favourite?

I’ve really enjoyed a sort of extended relationship with Silkworm. I’ve done quite a few records with them and I’ve gotten to see them develop over time and I feel like our working relationship has developed over time and is now very sympathetic. I really like all the Silkworm records that I’ve worked on. I don’t listen to that many records that I’ve done for entertainment. I really like the records that I’ve done with Will Oldham, the Palace records, I think those are really great.

Do you still refuse to accept royalties for any work you do?

That’s still the same.

Why?

I feel like whatever contribution I make to a record is, relatively speaking, trivial compared to the lifetime of effort and all the support work that needs to be done by a band itself for its own music. If a band spends years getting its act together, spends a year writing songs, gets those songs in shape, rehearses them, irons the bugs out, plays them live, develops a feel for them, knows them completely within themselves as an expression of their own creative impulse, then goes into the studio, sweats it all out, actually plays and performs the music, makes it sound good and from a performance level, and then after the fact goes out and drags their ass all around the country to promote the record on tour or build up a fan base, that means dramatically more than who was sitting in the producer’s chair at the moment that the record was being made. And I just think it’s an incredibly opportunistic and egotistic perspective for a record producer to think that he deserves any of the moeny beyond what he’s paid for the job. No one runs into a record store and says, ‘Do you have any records that were produced by Steve Lillywhite? I don’t care who the artist is, I just really want some records he produced.’ When someone goes into a record store to buy a record, they’re not buying a record because it was recorded by some dude, they’re buying it because they like the music or they like the band.

But your name on a record does help sales.

I appreciate that you think that, but I’ve made far too many records and I know too many of the bands involved. I know for a fact that me working on a record or not means nothing with respect to sales. What it does do is make journalists and people who work in radio station or whatever, it gives them their first reason to like or dislike the record. It doesn’t necessarily even mean that it will warrant their attention. It immediately allows the band to be categorized as one of those crappy bands that Albini records or one of those interesting bands that Albini records. Those opinions mean nothing with respect to sales. What will sell records or not sell records is whether or not people like them. They can like them for a myriad of reasons, none of which can be predicted. If you could predict why people like things, then everyone would make hit records. People buy records that they like.

How you do feel about your reputation as an indie-rock paragon?

It sort of depends on the connotation. If you’re saying that I am somehow the king of a very small and insignificant kingdom, well, then, I think that sort of dismissive perception of it warrants equally dismissive disdain from me, like ‘What the hell do I care what anybody thinks of me?’ If what you’re saying is that there is an artistically pure and honourable way to conduct yourself and I’m trying to behave in that manner, well, I would say, ‘Well sure, you’re right, that’s what I’m trying to do. I’m trying to be an honourable person in a game that encourages people to be dishonourable.’

How do you manage to maintain that state after so many years? Is it not tempting to take some bigger paycheques, if only to make things a little easier for yourself financially?

It’s never been demonstrated to me that there’s any advantage to going for the short-term money. Everyone that I see that does that suffers for it.

In what sense?

Well, for example, when I see bands go for what appears at the moment to be the brass ring; where they get a wedge of money for doing some sad corporate thing, like signing to a record label for what appears to be a lucrative advance. Every time somebody does something like that, if you follow their trajectory over time, they end up getting punished. Their fan base disappears, their sales dwindle, eventually they cease to satisfy whoever it is they’ve gotten into bed with and then the relationship goes sour and the band disappears. Whereas bands and people who maintain a way of doing things that’s true to their ethical perception of how people should behave, those people last forever. They stick around for a long time. I’ve been making records for almost 20 years.

So it’s honour, but it’s also good business sense?

It’s more a matter of self-preservation. At every turn, there’s somebody who wants a piece of you. It doesn’t matter what you’re doing in this life; at every turn, there’s someone who will offer you something for a piece of you. And if you take the something and give up the piece, you have to do it knowing full well that those offers aren’t being made blindly. The guy is getting more than he is giving, that’s why he’s making the offer. And eventually, people whittle themselves down to the point where they have a subsistence-level existence and the rest of the machinery is siphoning from them money and integrity and work and they can no longer enjoy their own lifestyle, their own career, because they’re doing it for other people.

I would think at your level of experience, you would have enough opportunities that would satisfy you creatively and pay you enough without selling out, so that you wouldn’t have to work seven days a week on so many small jobs.

The small jobs are the stuff that I like. The stuff that I don’t like is administrative work — seeing to the affairs of the studio on a business level or organizing stuff day to day. But I have precisely the same standards that I apply to bands that are on bigger labels as bands that are on the smaller labels. There’s no tongue in cheek; there’s no attempt to run a swindle involved. Whether or not a band is affiliated with a big record label is immaterial to me with respect to whether or not I want to do the record. Once I’ve figured out whether or not I want to do the record, if there’s a big record label involved, it becomes such an administrative nightmare and it becomes such a hassle on all fronts, because there are so many walls of bureaucracy to deal with and there are so many people trying to avoid paying me. More than anything else, that‘s the problem with big record labels, that they have the most resources and they are the biggest cheapskates. They are so difficult to get paid from; they love getting you to do work for them and then screwing you out of the money. And not being a victim to that institutionalized crookery requires a lot of time and effort and energy on my part to avoid being robbed when I’m dealing with a big record label. So I charge a lot more money for dealing with a big record label than I do for bands that are operating on an entrepreneurial level.

What’s the most memorable thing that you’ve turned down?

I’m a little bit self-conscious about mentioning this stuff for a couple of reasons. One, it sort of breeds intimidation among other people. It puts a spin on things so that I am the ultimate arbiter of taste, and lowly bands need not approach me because I will scoff at them. That makes me uncomfortable. I don’t like people to feel that just because it’s not appropriate for me to work on their record that I am in a position where I should be ragging on them. I’ll give you a categorical example. I’ve turned down stuff where it was obvious the band involved were not the people pushing for me. Where there were band members who’d never heard of me, had no idea who I was all about, but there was a manager and a record label person calling me on the phone and telling me they really want me to meet the band and work on the record, and I can tell it’s some sort of a beauty contest at that point. If they’re not familiar with anything that I’ve done, there’s no reason for me to work on their record. They could and should work with somebody generic, because its not in their interest to have somebody like me who has a fairly well-defined ideology working on their record if they’re not in tune with that ideology. Stylistically, the only things I’ve turned down are remixes. I just don’t like the whole idea of remixing other people’s work. I think it’s a trivial task and I think it’s been inflated into this bizarre superimportance because there are people who cant’t do anything else and in order to maintain their celebrity status, they have to keep doing remixes. I just don’t want to participate in that at all. I have no interest in the remix concept. Occasionally, very occasionally I have been asked to work on mainstream pop records, and I just don’t think that I have a feel for that sort of music. I don’t think I could do what’s required of a producer or an engineer in that environment.

How do you decide when to use the credit producer versus engineer?

By choice, I would never be called a producer. I see the title of record producer as a very specific thing. Something that I don‘t do, someone who takes directorial control of a record. I don’t do that and I don’t have a lot of respect for that as a working method. So I don’t consider myself a producer, and I know that the bands I work with don’t consider me a producer. Decisions that would be made by a title producer generally are made by the band when I’m in the studio. So the band should be considered the producer. It’s a convenient term for other people to use.

Back to Shellac: Is Terraform still the musical space you are in right now?

We work on a slower clock than most bands. We’ll propose an idea to each other and then a year later we’ll actually get around to trying it out. Then a year after than we’ll revise it and a year after that we’ll come to some sort of conclusion about it. So Terraform is not really indicative of a specific moment in our development; it’s more a collection of results that took five or six years to be generated. And I think that will be the case with all of our records.

But it’s not as if your new songs are 180° from those?

That’s a real difficult question for any musician to answer. To us, of course, we think that everything we do is radical and unique, that it has never been touched and has no relationship to anything ever heard on Earth before.

Structurally, you do break a lot of new ground. The songs seem to flow of their own accord as opposed to having structure foisted upon them.

I have to say we’re not big on verses and choruses. We tend to write songs in modules — this part, this part, this part — and then the linkages between them sometimes express themselves as different parts. But we haven’t done much by way of standard song — verse, chorus, verse, chorus, guitar solo, bridge, verse, chorus — kind of style.

You also seem to prefer using the guitar very sparsely as opposed to having it dominate.

I’m not as good a guitar player as I am a guitar not-payer. I think I don’t play the guitar really well. A lot of guitar players are really into all the stuff that they can play, all the parts that they play. The stuff that I like the best is the stuff that I don’t play. There are big parts in a lot of our songs where I don’t play a note, and I’m thrilled. That means there’s nothing for me to get wrong if I don’t have to play anything.