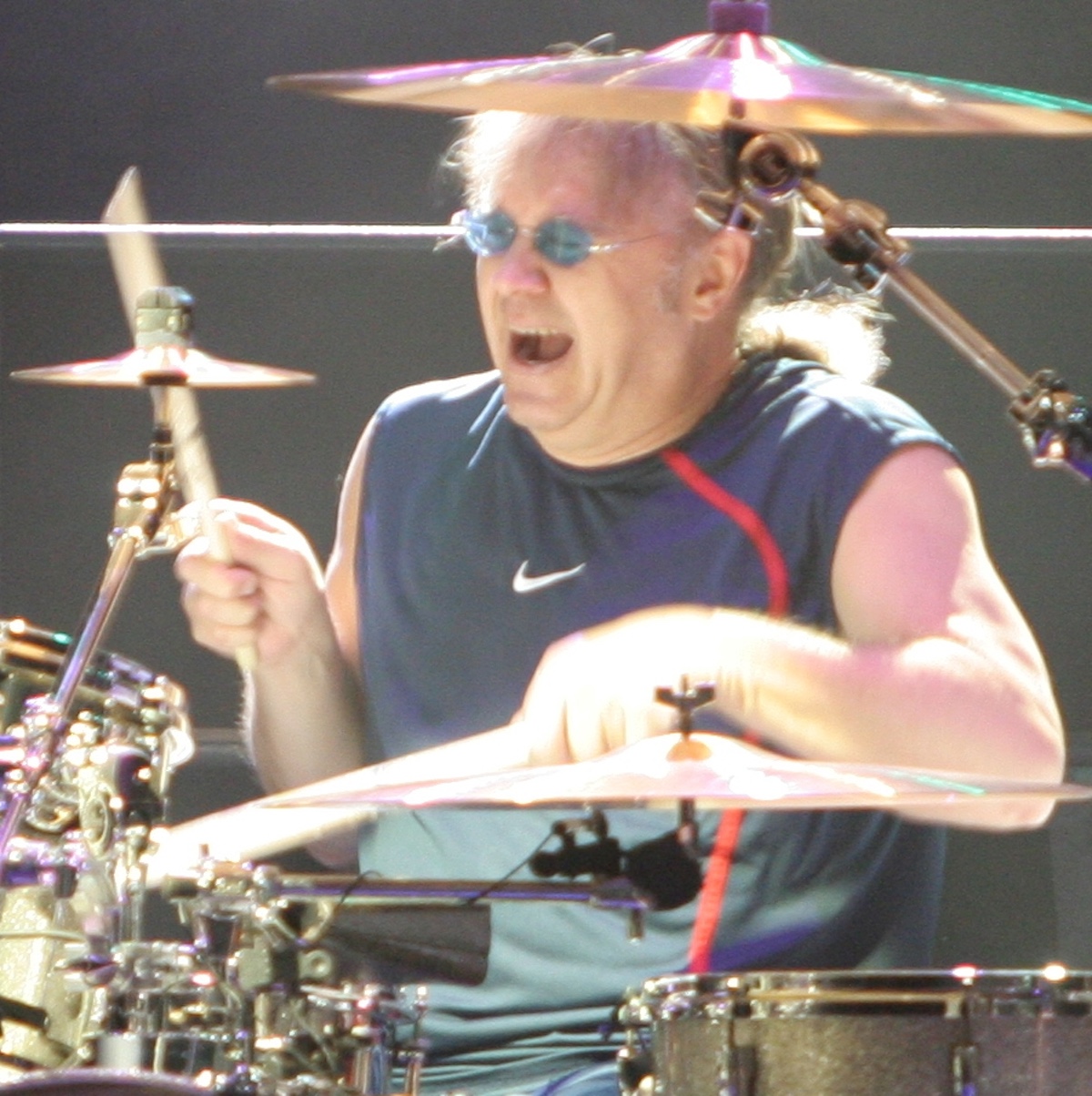

I love Deep Purple as much as the next old dude. So naturally, I’ve been digging the new Super Deluxe Edition of their classic 1972 LP Machine Head. The remastered updates of classics like Lazy, Space Truckin’, Highway Star and (of course) Smoke On The Water are a sonic revelation, and the new mixes by Dweezil Zappa (no, really) are truly inspired. Listening to it reminded me that I interviewed their explosively propulsive drummer (and longest-serving member) Ian Paice back in 2011 before a Canadian tour. Here’s the piece that ran in the paper and online — expanded with plenty of quotes that got cut for space back in the day. Enjoy.

Deep Purple will make no album before its time. Good thing it’s finally about time. Drummer Ian Paice says he’s “almost positive” the British arena-rock gods — whose last record was 2005’s Rapture Of The Deep — will hit the studio in 2012 to cut their 19th studio album.

“I believe that we have another good record in us and I believe we’ll make it this year,” says the 63-year-old rocker, blaming the delay on dissent within the ranks. “A couple of years ago there were a couple of guys in the band who just didn’t see the point. And when it’s like that there’s no use trying to push it. But there’s been a change of heart. I want to do it just because I think it’s good that we keep coming out with new music. It’s good for our fans that they still see us trying to give them something different to listen to. I don’t care how successful is it. Financially, most people know that making records is not what it used to be.”

Thankfully, touring is another story. “We play to more people now than we have in the past 20 years. We have to turn down work.” Some gigs they didn’t decline: The largest Canadian tour in their 44-year history. Singer Ian Gillan, bassist Roger Glover, guitar player Steve Morse, keyboardist Don Airey and Paice — the sole constant in the group since its inception — will play 17 cities in 24 days on their Smoke On The Nation run, beginning in St. John’s and wrapping up in Vancouver.

From a Caribbean holiday villa where he was soaking up some extra rays before braving the Great White North, Paice discussed the various shades of Purple, forgetting about The Velvet Underground and getting into the Rock And Roll Hall Of Fame. The highlights:

You’ve been touring with an orchestra. Has that been fun or just a pain?

The orchestra’s been great because the show’s not classically led. It’s just a rock ’n’ roll show with different sounds. In Europe, we used the same orchestra throughout the whole tour, and by the end it was just wonderfully tight. They were just like another bunch of guys who were part of the band. But in Canada, it’s just going to be the straight rock ’n’ roll show. In North America, the distances between cities are so great; moving that many people around is incredibly expensive. Or you have to pick up new orchestras in every town and rehearse them. And quite honestly, there just aren’t enough hours in the day.

From what I understand, you guys don’t rehearse much anyway.

So many of the songs that we play — and have to play and enjoy playing — have been in our psyche for so long that you don’t forget them. If we do want to change something, we’ll take 10 minutes in the dressing room before the show and just say, ‘OK, let’s add another bit to the solo’ or ‘Let’s change the ending.’ It’s no big deal. The thing with playing old songs is that you have to keep it interesting. If you just go on autopilot, people would notice. We would be bored playing, and that would transmit to the audience and they would be bored listening to it. But when we’re having fun with it and changing the old little bit here and there, it stays fresh for us and for the audience.

You’re the only guy who’s been there for the duration. Roger Glover told me you ‘the soul of the band.’ Do you feel like the boss?

Nah. It’s just that when (keyboardist) Jon Lord left, somebody else had to step up to the plate. And it just turned out to be me this time. Other guys have different things they’re good at. I play drums OK and it’s turned out that being the lead mouthpiece works OK too.

Are there any perks or privileges that come with the job?

Unfortunately not.

I would think you’d at least get to have the last word in arguments.

Well, what generally happens is that like any band — which is like a marriage of four or five souls — you’re going to get disagreements. I just try to be the guy that takes the logical point of view; the guy who says, ‘Look, we can argue about this until the cows come home, but it’s not going to change it. How do we fix it?’ I’m that sort of guy. And every band needs one. Because you get people who have incredibly strong views about something and they won’t see the middle ground. So somebody has to be that negotiator in the middle to bring the harmony back in.

Aside from the current lineup, which incarnation was the best one in your opinion?

Well, best is a strange word. There are times when the lineup was correct for what was going on. Obviously when Mark II (with guitarist Ritchie Blackmore and Lord) came along in late ’69, that was an incredible lineup. That band was absolute perfection for that period of time. We had so much virtuosity in the band that we could extend things beyond the realms of most bands. We could take a three-minute song and turn it into a 10-minute song and not lose the audience. That was right for that time. To try and do that today is much more difficult. People want more songs. They want to get as much as they can in the time you’re onstage.

Speaking of pushing the envelope, is that the plan with the next album?

Every time you go into the studio, you try and have that possibility in mind. But it doesn’t always work. Really, it would just be nice to get a really strong album together with a really great sound. It sounds easy, but that’s really our downfall. We’re so egocentric — each of us — about our own sound that sometimes it can be negative in the end product. You really need a great sound guy to ignore all of our personal wants and just give us the best-sounding record we can get. Basically, we have to be outranked in the studio — even me. Because it’s quite simple: If you play straight up-and-down rock ’n’ roll, you can get an incredibly big sound. But all the little nuances that you play if you have a little bit of craft get lost, so you’re very protective about the bits that you play that you think people should hear. Whereas the producer will go, ‘That makes no difference to the guy listening to it.’ So you need that sort of cold, outsider point of view to say, “This is what’s needed; that really is unnecessary.’ As the artist creating it, sometimes it’s very hard to disassociate yourself from what you did.

Shouldn’t you be in the Rock And Roll Hall of Fame?

Yes we should. But as it’s taken so long, I’ve a mind that if it ever comes up, I would probably refuse it. I think it would probably be insulting. That’s my personal view — I’m not speaking for the other guys in the band. But I’ve seen so many nonentities get into it that I’m not sure it’s that hallowed a place anymore. (NOTE: They were finally inducted in 2016. They did not refuse it.)

As a drummer, you’ve got a more physical role. How are you holding up and how do you keep in shape?

I’m fairly lucky. I am incredibly fit for my age. I have the advantage of having a technique which allows me to play with a great deal of volume without using much energy. The years teach you how to do it more economically. I see kids playing who are maybe half my age and they don’t have what I’ve got.

Is it true you played drums on The Velvet Underground’s 1972 album Squeeze?

This keeps coming up, and honestly, I had completely forgotten about it. I remember doing a session in New York. But I could not remember who it was for. Somebody played me a track and told me it was me a few years ago. When I listened to it, I thought it sorta sounded like me, so it could be. But other than that, I have no recollection whatsoever. It was just one day of my life.

But you did play on William Shatner’s version of Space Truckin’, right?

That was one of those wonderful glories of modern technology. I just sent over the basic files for the track. I gave them a couple of options of drum takes that I did in my little studio at home, and they chose the one they wanted and that was it. Johnny Winter is on the track as well, and he did his thing somewhere else. I’ve never personally met Mr. Shatner, though I got lots of nice emails from him.

There’s been a small avalanche of archival Purple releases lately — some with previously unreleases live recordings or studio rarities. I presume the band has no input in many cases. Does that bother you? How do you feel about these kind of releases?

Depending on the quality of the recording and the playing, sometimes you look back and say, ‘Yeah, that was pretty good. I wonder how we lost that.’ And other things you look back and say, ‘This wasn’t released because we didn’t think it was good enough then, and we don’t think it’s good enough now.’ But yeah, it’s taken out of your hand sometimes. I think the real devoted fans will listen to anything you did and put it in their archive, good, bad or indifferent. And for that, I feel neither one thing nor the other. We did it. And if we got it wrong, we got it wrong honestly or because we just weren’t up to it that night. If we got it right, that’s incredible. If it sounds good, fantastic. If it doesn’t sound good, there’s nothing you can do about it. So I take a pretty ambiguous stand on it. If it keeps somebody happy and it doesn’t destroy my career, I can’t complain.

You’re all getting up in years. Do you have an exit strategy?

The exit strategy will be to stop when one or more of us physically cannot cut the mustard. I don’t think there’s any point in being a mere shadow of yourself. So that’s when it would go. Or if the audience stops coming, but that doesn’t seem to be happening.