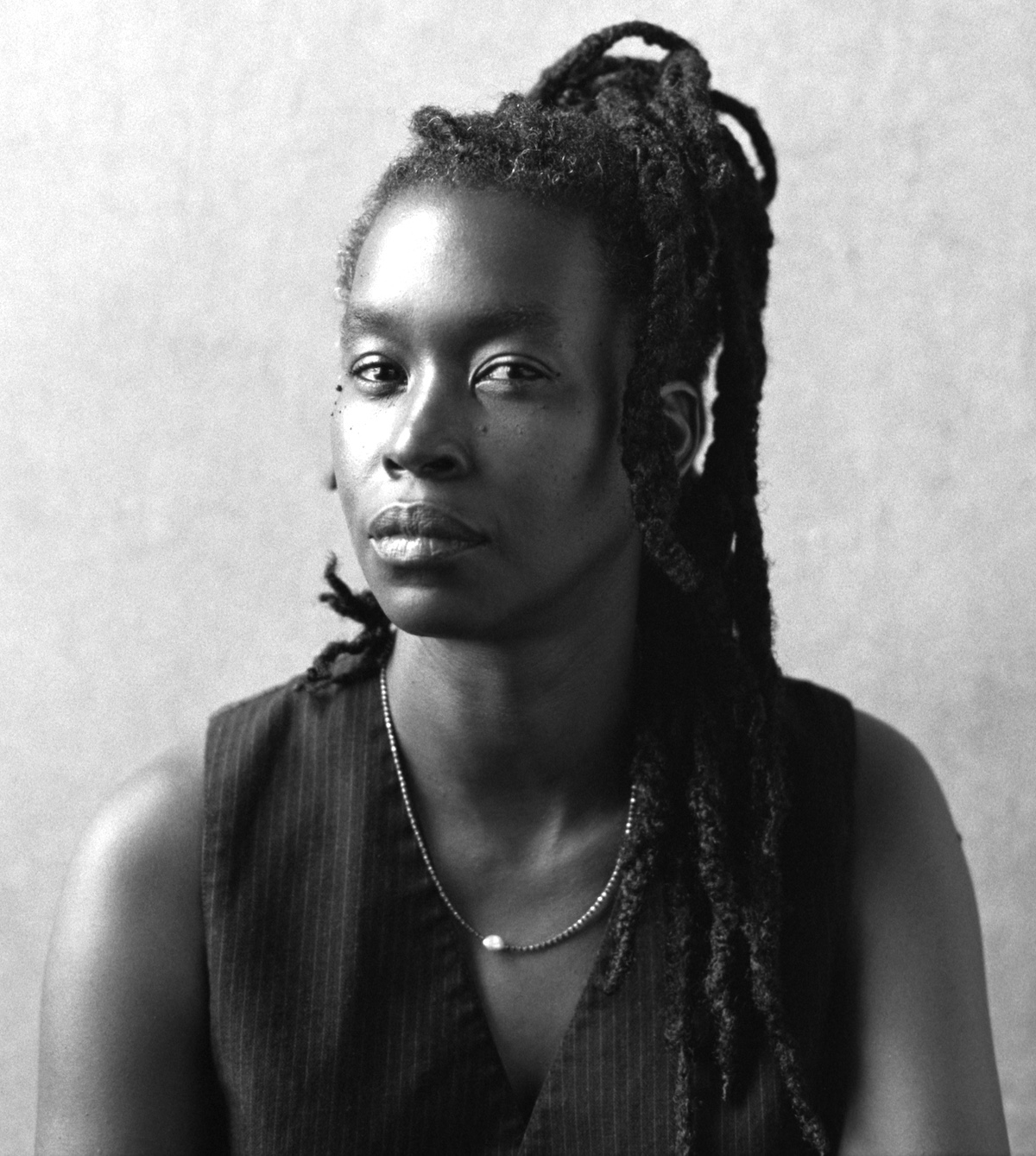

THE EDITED PRESS RELEASE: “How do you engage the stunning, evocative, haunting gift that is Moor Mother’s latest album The Great Bailout? Only by following the trail of verbal and sonic poetry delivered. Only by letting Moor Mother and her co-conspiring collaborators — Lonnie Holley, Mary Lattimore, Alya Al Sultani, Kyle Kidd and more — “people who have their own path of positivity and connectedness” be the tour guides.

The Great Bailout is the ninth studio album from Moor Mother (aka Camae Ayewa). Dubbed “the poet laureate of the apocalypse,” Ayewa’s music contains multitudes of instruments, voices and cacophony that take on themes of Afrofuturism and collective memory with the forebearers of jazz, hip-hop and beat poetry in mind.

So: Come! Come look! Come see! Come hear! Come see London, come see Liverpool, for the first time even if it for the millionth. Know its provenance, know its haunting. Clear the mist over your eyes and heart as if the famous London fog has been cleared by the clarion call of Moor Mother. For this is what The Great Bailout is: A call to knowing through a sonic scene that is unafraid to look a violent legacy in the eye.

“Research is a major part of my work, and researching history — particularly African history, philosophy and time — is a major interest,” Moor Mother explains. “Europe and Africa have a very intimate and brutal relationship throughout time. I’m interested in exploring that relationship of colonialism and liberation, in this case in Great Britain.”

So what is the terrain we are invited to navigate? Think: Two acts of Parliament. First: The 1833 Slavery Abolition Act that established a four-year period of ‘apprenticeship’ during which the enslaved in the British Caribbean would transition from being ‘slaves’ to being free. And the 1835 Slavery Abolition Act — a loan that allowed the British Government to borrow £20 million (£17 billion in today’s money) with which to ‘compensate’ 46,000 slave owners who were losing their ‘property’ because of the legal abolition of slavery. A loan that was one of the largest in history. A loan that equaled 40% of the treasury’s annual income. A loan that was only finally paid off in 2015. A loan that all payers of tax in the U.K. helped to pay off — which means that all those descendants of the once enslaved, including the so-called Windrush Generation, also helped to pay off.

Think: Not one of the enslaved received a penny in the form of compensation. Think: Two British prime ministers — William Ewart Gladstone (PM on four occasions between 1868-1894) and David Cameron (2010-2016) — both of whose ancestors received ‘compensation’. Think: All of this through the prism of two acts and the histories they encode, and you know the terrain of The Great Bailout. “Displacement and its effects are not discussed enough,” Moor Mother says. “The PTSD of displacement should be a focus, and as we have the opportunity to learn about things happening in the world, we also have the opportunity to learn about ourselves. We’ve been through so many different acts of systematic violence.”

Evocative of the multiple echoes on Bailout, there’s one here. Speaking on the release of her 2017 debut album Fetish Bones, Ayewa, said: “We have yet to truly understand what enslavement means, what it does to people. It’s programmed within us, there’s no way to escape it.”

In thinking about that reckoning with haunting and material indebtedness, with truth searching, she made it clear that her vision stretched far and wide, not restricted to the U.S. alone because she doesn’t see the people of the African diaspora as separate, just dispersed. As she told me, “I have a hunger to meet each other all over the world,” with London being among the key stopping points. But first where to find people. “I’d been to London a few times and couldn’t find things — like where were all the people?” It is an invisibility that is an effect of the “taxpayers of erasure,” until she headed south to Brixton and she saw one of the places where we are.

Now we are oriented, travelers, let’s enter the portal. The tender, atmospheric Guilty starts our tour through the haunting, rendered by the gentle, almost melancholic instrumentation and calling forth the crimes that were paid off but still live. The exquisite beauty and horror conjured in the song is simultaneously dream and traumatic nightmare. Guilty is astounding for the poignancy and tenderness in which it invites us to dwell in our journey of facing Britain’s not just complicity in enslavement and its afterlives, but also its very making as a built environment and social-political formation.

The next track, All the Money, shifts to a more sinister register of voice and instrument. The feeling of water remains as ‘the storm keeps raging’, but now as a drowning, conjuring the many captured black lives swallowed in the waters of the transatlantic crossing, currently in the Channel as people seek asylum, and the continuing drowning out of this British history, and the drowning out of black lives living in London, Liverpool, and multiple port towns were the ships docked and the holds carried their festering lives known as property.

This movement, indeed, entanglement, between gentleness and horror, rage and grief, is the warp of the long poem that is the album. The dominant narrative, the top note, is a calling out in the words and in the sound: ‘You think Britain’s complicity and indebtedness to the enslaved is all invisible or past, well now you see that the whole country is pockmarked by the violence and money of enslavement.’

Running in parallel to this is the thread of black life as freedom, black life otherwise, it’s in the music, the sonic landscape that is Moor Mother’s black music making as freedom and in the legacy bequeathed by earlier generations of black music makers, she so keenly honours.

Hear the echo of Sarah Vaughan on Liverpool Wins, as Kyle Kidd’s exquisite vocalisation soars above and shudders under, and circles alongside the story of the making of Britain and indeed Europe based on bodies robbed, caged, devalued. Land colonized and sequestered. Hear something of Lester Bowie, mildly filtered through Pat Metheny on God Save The Queen, or the gritty edge of Nina Simone’s voice of contempt when she sang Four Women, as Moor Mother calls “God, god, god save the queen” on the same track and the track that follows Compensated Emancipation.

The album’s tribute to black life as freedom even as the album is making black life as freedom, is the balm that makes the journey into the hauntings and contemporary life of antiblackness and other modes of the colonial that saturate this “sceptred isle” that is Britain.

But this demand for national reckoning is not in service of national rehabilitation. Indeed, the cry of Liverpool Wins, in echo of the announcement of the sports commentator at a football (soccer) game, reminds that slaving port cities keenly competed to be the greatest in the making of imperial Britain, with its infrastructures and monuments dripping in blood. “I knew I wanted to talk about Liverpool and the competition between cities, you know, everyone has their football team,” Ayewa said, “but (intercity competition) is like a petty nationalism…it’s going nowhere.” So alongside the mime of the match commentator, we hear the rendition of repetitive action on two sides of the plantation relation: a cutlass cropping, a cash register counting.

Into this warp is the weft that is the challenge of recognizing history in a way that disrupts the given historical narratives, a thread of continuity and reimagining that runs across her work. Here The Great Bailout continues Moor Mother’s practice from 2022’s Jazz Codes and her work with Rasheedah Phillips as Black Quantum Futurism.

This is one way onto the tour to which you are invited by The Great Bailout. Or you can just breathe and enter and be required to reckon with a horror story hiding in plain sight, and be lifted by the poignant beauty that is black poetry and music making as freedom in the otherwise and ‘everywhens’ mediated through a journey into Britain.

If you can surrender to that, then the experience of this stunning work is boundless as the logics of capture are escaped on the rise of the opera voice as it soars (All The Money), the clarinet dances and entices (South Sea), as the blues sing from visceral self-possession (My Soul’s Been Anchored). Simultaneously in the continued grip of the hold and legacy of ‘compensation’ and on fugitive, creative run from it, The Great Bailout offers a listening that nourishes.”