It’s like, “How much more Canadian can it be?” And the answer is, “None. None more Canadian.” The cover of Rush’s 1981 album Moving Pictures is basically the equivalent of a beaver full of Screech, plowing through the set of The Nature Of Things on a snowmobile.

It’s like, “How much more Canadian can it be?” And the answer is, “None. None more Canadian.” The cover of Rush’s 1981 album Moving Pictures is basically the equivalent of a beaver full of Screech, plowing through the set of The Nature Of Things on a snowmobile.

Let’s start with the music. Moving Pictures was, and remains, Rush’s biggest-selling album. It hit No. 1 in Canada and No. 3 in the United States and U.K. It sold more than 400,000 copies in Canada — went platinum in just four weeks — and sold 100,000 copies in the U.K. and more than five million in the U.S.

On June 22, 1980, Geddy Lee, Neil Peart and Alex Lifeson wrapped up touring the previous record Permanent Waves, in Brighton, England. The tour was the first to turn a profit for the band, which had been working to build a following the hard way — with gigs instead of hit singles. They played around 200 shows a year for three years straight. Mostly in an RV and tour bus.

No surprise then that the initial plan had not been a studio record, but to put out a live album — a successor to 1976’s All The World’s A Stage. But spirits were high due to the tour — and the band was excited about the new songs and song fragments they’d been coming up with between shows and during soundchecks. So rather than compiling a live album, the three men said hello/goodbye to their families and arranged to meet up at their retreat in Stony Lake near Peterborough to write and rehearse material for what would be their eighth studio album in six years.

But first, perhaps still jetlagged, they paired up to record the track Battle Scar with labelmates Max Webster, who were recording Universal Juveniles at Toronto’s Phase One Studios during the summer of 1980. This might seem, at first blush, like a pain in the ass, but it turned out to be more than a little fortunate. The primary lyricist for Max Webster was Pye Dubois. During the session, Dubois shared an idea he had for a song with drummer/lyricist Peart. Maybe you know it…

“A modern-day warrior

Mean, mean stride

Today’s Tom Sawyer

Mean, mean pride.”

The time in Stony Lake was productive, so the band went back to Phase One, just vacated by Max Webster, and recorded demos of the songs they’d come up with — Tom Sawyer, Limelight, The Camera Eye, YYZ and Red Barchetta. This way they could be close to their families before they hit the road AGAIN on Sept. 11 for a 16-show tour to tighten up the new songs ahead of scheduled recording sessions at Le Studio in Morin Heights, Quebec — where they’d recorded Permanent Waves. They needed to wait for The Police to finish up work on Ghost In The Machine first. The warmup tour ended Oct. 1 in Portland, Maine, after which the band simply headed eight hours north to Le Studio, where they would spend the better part of a month making Moving Pictures. The album hit shelves on Feb. 12, 1981 — eight days before the band started a 95-show promotional tour of North America.

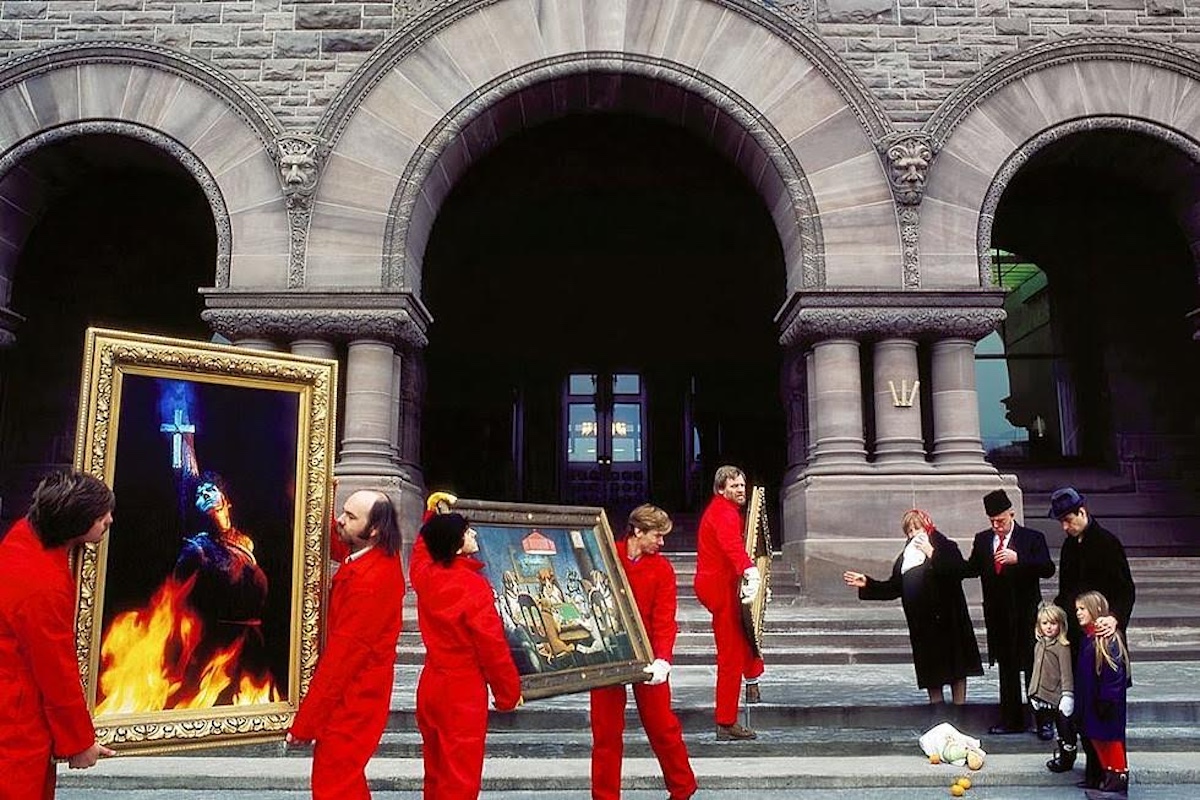

Torontonians (and those who follow Ontario politics) would have recognized the setting on the cover of Moving Pictures right away — the front entrance to Queen’s Park, meant to sub for an art gallery or museum. At the time, the place would have been a ghost town. The same week Moving Pictures dropped, an election campaign began. All the legislature fanned out to ridings across the province for a campaign which would end with Bill Davis’s provincial Tories winning a majority after two successive minority governments.

I don’t know where the name Moving Pictures came from — it’s not in any of the lyrics. But the band chose the title and Peart called longtime art director Hugh Syme to tell him so he could come up with ideas. As usual, he had a good one — a double pun. The album artwork shows a crew of movers in red jumpsuits, literally moving framed art — pictures — into the building. Watching them are what appears to be a family overcome by emotion. You know, because these are very moving pictures.

The sleeve art actually has a third pun on the back cover — a wide shot which shows the scene on the front being filmed by a crew for a “moving picture.” In reality, the crew were actually filming, and the resulting footage was shown during concerts on the subsequent tour.

Let’s unpack the elements of the cover. There are three paintings in ornate frames being carried into the building — one of Joan of Arc being burned at the stake, a second famous painting of dogs playing poker that Peart really wanted, and a third featuring the Starman logo from the band’s 1976’s album 2112. Syme was able to acquire the latter images, but he had to create the Joan of Arc painting himself from scratch. For this, he used the album sleeve’s photographer Deborah Samuel as a model. Samuel not only took the photo for the sleeve of Moving Pictures, but she also did the ones for Signals, Exit Stage Left and Permanent Waves.

When Syme did the original artwork for 2112, he used his friend and assistant Bobby King as a nude model for the Starman. He did this again for the Magritte-like man-in-the-hat on the cover of 1978’s Hemispheres. Not only does King’s likeness appear on the cover of Moving Pictures in the form of Starman, but he’s also the mover on the far left (with the moustache). He reprises this role on the cover of the 1981 live album Exit… Stage Left.

The balding mover helping King carry the picture of Joan of Arc is Mike Dixon, a friend of King’s who got him involved as a member of Syme’s design team. Behind him, holding up the left side of the dog painting, is waiter Mario Prudente. I have no idea who is holding up the other end of that painting.

If he wasn’t obscured by the Starman picture he’s carrying, you might have recognized that mover as the late Kelly Jay (Blake Fordham) — the lead singer, keyboard and harmonica player from Canadian rockers Crowbar. You know, the guys who sang “Ohhhhh what a feelin’ … What a rushhhhh.” Get it? Anyway, Jay’s wife Kerry Knickel was good friends with Samuel the photographer. She invited Kelly to be one of the movers. Knickel was a makeup artist, and served as such for the photo shoot. In fact, you can see her on the back cover — far left, with long, dark hair, looking over some notes.

Something of a legend, Jay’s shtik back in the day was being provocatively Canadian — fur-trader hats and buckskin jackets with maple-leaf emblazoned boots. Dubbed Captain Canada, he had a big beard and stood 6’4”. Oh What A Feeling came out in 1971 on Crowbar’s second album Bad Manors — named after Jay’s infamous Hamilton-area farmhouse. This was the dawn of Can-Con regulations, and Oh What A Feeling was the first hit single after they went into effect. To mark the occasion, Jay presented them-Prime Minister Pierre Trudeau with a plaque which read “THANK YOU FOR MAKING IT POSSIBLE FOR CANADIANS TO BE HEARD IN THEIR OWN COUNTRY.” Legend has it he then slipped a couple joints into the PM’s pocket. He also had a stripper jump out of a cake during one of Crowbar’s shows at Massey Hall. Rush likely first met Jay when the band opened for Crowbar and King Biscuit Boy on Feb. 19, 1971 at the old Minkler Auditorium at Seneca College. This was something like the band’s 15th gig.

Like I said, Jay was a legend. But all that happened a decade before he appeared on the cover of Moving Pictures. Crowbar broke up in 1975. When Syme got Jay involved in the album cover shoot, he was working as an overnight DJ on CHUM-FM in Toronto. A few years later he moved to Alberta and faced tragedy after tragedy. His daughter, who worked in Tokyo, went missing in 1997. She’s never been found. The mother of three of his kids, Katherine Marsden was killed in a car crash in 2006, and in 2012 his then-wife Tami died of heart disease. Jay’s finances dwindled and he ended up beset with diabetes and syllogomania — the disorder associated with hoarding. In fact, Jay was the subject of an episode of Hoarding: Buried Alive in 2013.

When he died in 2019, a GoFundMe was started to help his family pay for the funeral as well as legal bills and mortgage arrears. I’m not sure what he was paid to be part of the Rush cover shoot, but it was an expensive undertaking overall. The final bill was around $9,500, which Anthem Records reportedly refused to cover, insisting the band pick up part of the tab.

The emotional peasant family on the right of the cover were friends and family of Samuel, but the band itself isn’t on the cover at all — just pictured in three fantastic motion shots on the inner sleeve, shot by Samuel and Syme at Le Studio. There are some fans who suspect the man smoking in the middle of the back cover is Peart — but Syme will neither confirm nor deny this.

This really was Rush’s golden era — from the release surprise hit The Spirit Of Radio, the Permanent Waves tour, appearing on a Max Webster album in late 1980, Moving Pictures and then the biggest chart success related to Rush: Lee joining SCTV hosers Bob & Doug McKenzie for their song Take Off in 1981. Geddy only spent 15 minutes in the studio — wearing a toque — with comedians Dave Thomas (brother of Canadian musician Ian Thomas) and Rick Moranis (an elementary school classmate of Lee). The song eventually hit No. 16 in the States — higher than any Rush song.

Syme and Samuels won the Juno for album artwork for Moving Pictures and were also nominated in the same category for Exit… Stage Left. Rush were nominated for Group Of The Year, but lost to Loverboy. I believe they were nominated in this category 15 times and won twice (1978 and 1979). Moving Pictures and Exit… Stage Left were both nominated for Album Of The Year — but lost to Loverboy‘s self-titled album. The Great White North album, featuring Take Off, won the Juno for Comedy Album.

• • •

Area Resident is an Ottawa-based journalist, recording artist, music collector and re-seller. Hear (and buy) his music on Bandcamp, email him HERE, follow him on Instagram and check him out on Discogs.