When I’m not listening to an album, watching a video or posting something about music, I’m probably reading about it in a memoir or biography. Like this one:

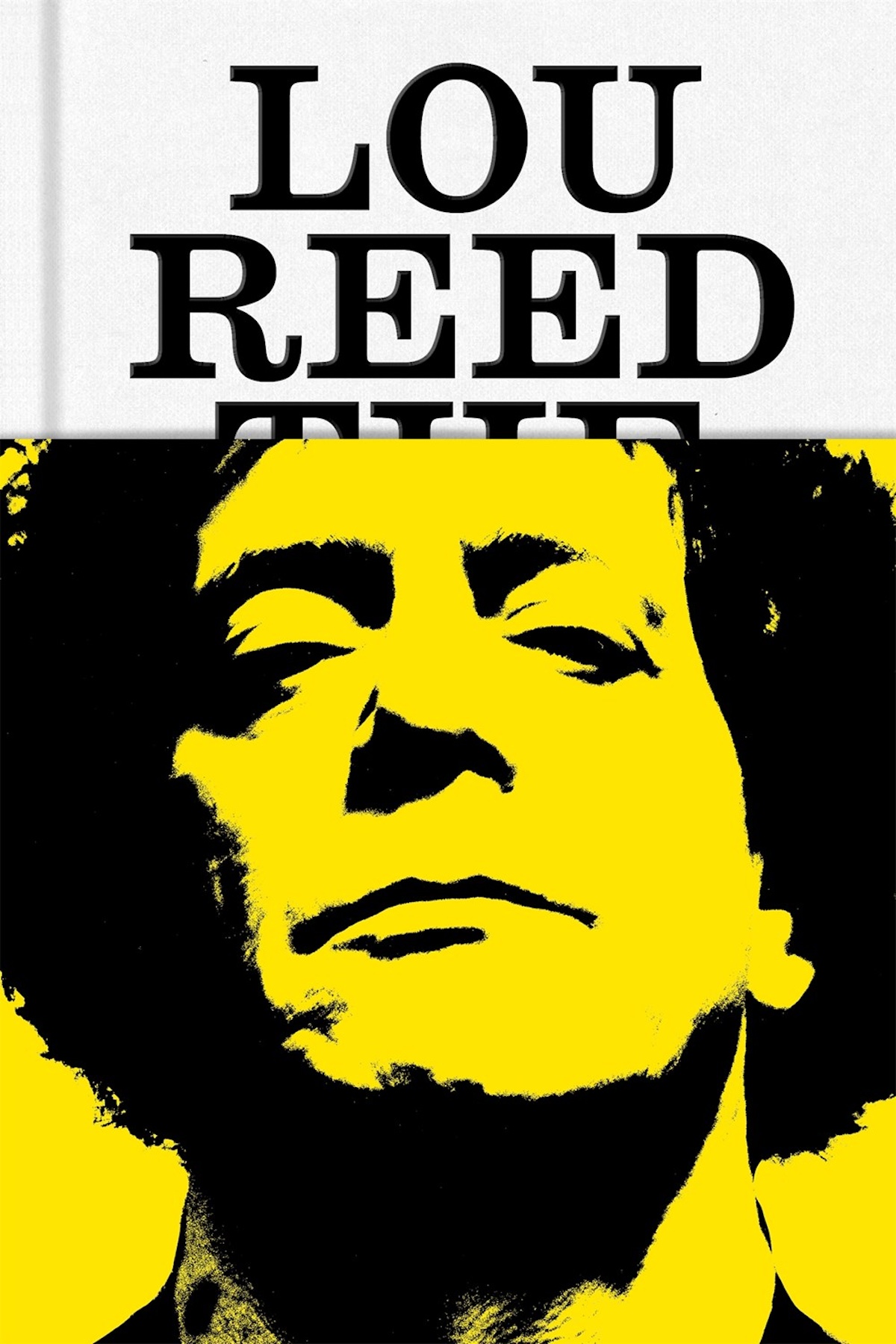

Lou Reed: The King Of New York

Lou Reed: The King Of New York

By Will Hermes

Lou Reed: Over His Goddamn Dead Body might have been a better title. Or at least a more accurate one, given the misanthropic rock icon’s notorious hatred of journalists, interviewers and writers. Exhibit A: Reed once thwarted a would-be biographer by mailing a form letter to friends and colleagues, asking them to shun and snub the offending author.

One can only assume he would have been equally enthused over this dandy little number from veteran music scribe Will Hermes. And rightly so, perhaps. Not that there’s a damn thing wrong with The King Of New York. As you would expect from a former editor for Spin and contributor to Rolling Stone (among many other publications), this an extensively researched, well-written chronicle of the singer-songwriter, Velvet Underground overlord, longtime musical provocateur and first-rate son of a bitch’s life and career.

Despte (or more likely because of) that, Reed would surely hate how probing, informative and revealing it is. Over its 500-plus pages, The King Of New York brings to light every dark facet of Lou’s public and private existence: Dyslexia, shock treatments, neurodiversity, non-binary sexuality, substance abuse, conmercial self-sabotage, ruined romances and of course, his eternally, uncompromisingly antagonistic, volatile and complex relationships with his father, Andy Warhol, John Cale, Lester Bangs, various lovers and, frankly, almost everybody else in his life (with the possible exception of Barenaked Ladies member Kevin Hearn, who spent several years in Reed’s band without incurring his boss’s wrath, as he told me when we spoke a while back).

Naturally, I got way more of a kick out of the musical side of things — like learning that Reed sometimes wrote his albums in a day or two (which explains a lot about some of them, unfortunately), reading that he challenged Metallica’s Lars Ulrich to a fight while they were recording Lulu, or finding out how much money he got from licensing and/or enforcing his copyright on Walk On The Wild Side over the years (condolences, A Tribe Called Quest). Personally, I was less interested in the details of his fluid sexuality, unrequited loves and romantic troubles — though to Hermes’ credit, nothing here is lurid, shocking or sensational; it’s all tastefully, honestly and respectfully presented, reminding us just how far ahead of his time Reed was in this department, both artistically and personally.

And of course, now that Lou’s gone, Hermes likely didn’t have nearly as much trouble getting friends, family, fans, former bandmates and fellow artists to talk about him at length, without fear of recimination or reprisal. As a result, A King Of New York has got to be the most detailed portrait of Reed ever created — and perhaps the definitive biography of one of the late 20th century’s most influential and important artists. Even Lou shouldn’t be too pissed off about that. Though he probably would be.