Too much music, not enough time. That’s the story of my life. Even though I spend an absurd number of hours every day listening, watching, reading and writing about new performers and old favourites, there are still countless artists I wish I had more time for. Like Nick Cave.

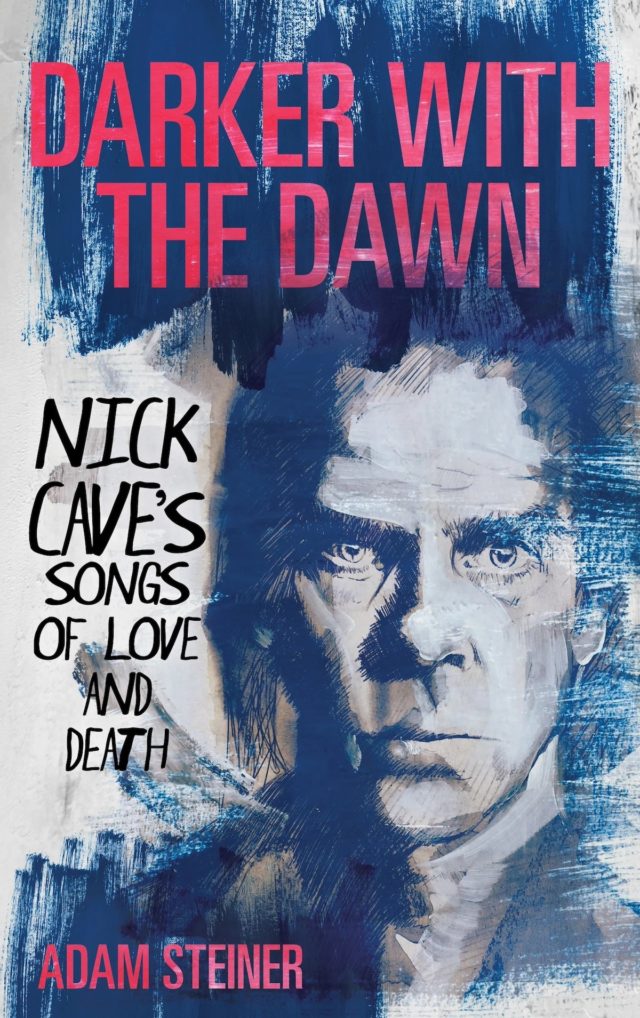

Don’t get me wrong; I’ve heard all his albums repeatedly — from his days with The Birthday Party to The Bad Seeds and Grinderman. I’ve seen him live. I even interviewed him once. But I still feel like I’ve barely scratched the surface with him. I’d love to find the time to do a deep, focused dive into his entire catalog. And if/when I do, it will surely happen as I’m reading Adam Steiner’s exhaustively detailed and thought-provoking new book Darker With The Dawn: Nick Cave’s Songs Of Love And Death. Over the course of 300-plus pages, the London author — who has also written Into the Never: Nine Inch Nails and the Creation of the Downward Spiral and Silhouettes and Shadows: The Secret History of David Bowie’s Scary Monsters — casts his critical, scholarly eye over the history and deeper meanings behind Cave and The Bad Seeds’ best-known songs, from Tupelo, The Mercy Seat, Red Right Hand, Stagger Lee and Into My Arms to Higgs Boson Blues and beyond. Here’s an exclusive excerpt, courtesy of the author:

BAD BLOOD

“Of man’s first disobedience, and the fruit

Of that forbidden tree, whose mortal taste

Brought death into the world

Sing heavenly muse.”

— Milton, Paradise Lost

The first few lines that open Milton’s classic epic poem speak about the fall of man manifest in humanity’s crimes of murder. In his songs Cave is less concerned with the idea of ‘pure’ evil and the rule of God’s law, than in actions against other people; seeing life as a daily mass of contradictions. In Red Hand File #196 he argues, “There is no problem of evil. There is only a problem of good.” Goodness seems only to emerge in spite of bad and terrible things, not as a corrective. Indeed, what we might call “evil” actions are not prescribed by some other power; individual responsibility remains. As with the tragedy of Humbert in Lolita broken by his need for illicit love and even his desires have consequences, and while Cave’s songs of punishment don’t suggest that the bad will always suffer, he spends more time in exposing the fallout of their misdeeds, and in that sense the songs throw up moral issues, without passing judgment or demanding answers. The great strength behind Cave’s lyrics is his boilerplate ambiguity, giving him moral flex but also a continued interrogating force behind the songs.

Cave’s earlier misanthropy and pessimism often indulges wrong against right, where the “good” person is at once both a sucker and a victim. His songs show a creative mind drawn towards aggressive tragedy: “I don’t deny any feelings of happiness just because I don’t write about them. For me, there’s just something more powerful in Man’s ultimate punishments — whether they’re on a humanist level or a more mystical level — than in his ultimate rewards. The rewards of happiness and contentment and security, I see as mostly drawn out of a routine of things. And they have no aesthetic interest for me, or much lasting value.”

The opening lines that begin Milton’s Paradise Lost speak as much about the fall of man through Adam and Eve’s temptation as they do to man’s crimes against humanity and the first intimations toward original sin. The literary critic George Steiner suggested that the 20th century would gradually reveal the upended balance of natural Godly law: “If, in the Judaic perception, the language of the Adamic was that of love, the grammars of fallen man are those of the legal code.” Adam and Eve’s shame condemns them to mortality. This first unconscious rebellion of mankind becomes the hinge of Cave’s 1990 song from the eponymous album, The Good Son.

It begins with a laconic chant, “one more man gone,” which John Mulvey hears as “The Bad Seeds’ chorus of rude mechanicals, aping the chain gang ardor of an American spiritual.” Cave uses the biblical story of Cain and Abel from Genesis 4:1–18 to explore humanity’s first confrontation with murder, setting the pattern of original sin for mankind to follow. The first two sons of Adam and Eve are Cain and Abel. Cain is a hard-working tiller who works the field, whose offerings to God are rejected. The eponymous good son, Abel is favored both by his father and God, who only asks that he be righteous and resist the temptations of sin. Cain jealously murders his brother to take his place and become the only son. When God asks Cain where Abel is, he responds with the immortal line: “I do not know. Am I my brother’s keeper?” Cain lies to God, knowing his brother is buried in the fields that he had worked on all of his life, just as Abel’s “blood cries out from the ground.” Cain’s declaration divorces him from his fraternal bond, denying the lifeblood shared with his brother, the one who he feels as again always moved upon his heel. His outspoken questioning is a choice, a conscious break from God’s word and his grace.

The Good Son can seem ambiguous, dividing sympathy between both Cain and Abel. Cain, for a time, does the right thing by his family as any loyal son should, but eventually snaps as he is doubly tested by the favor of God and his father, Adam. Abel will always remain the innocent victim, the chosen son who was allowed the easier life of the shepherd. It is Cain the firstborn’s struggle to endure his second-best status where Cave finds, “It’s a malign star by which the good son’s kept,” suggesting his thwarted future.

Again, life for one brother seems to default to death for the other, their fates intertwined. The story presents a stark view of unnatural death, where Abel is killed before his time of old age. But in exposing our more animalistic human behaviors, the story helps to polarize our notion of good and evil, and punishment. In the story’s aftermath Cain’s woes are intensified. He must carry the burden of guilt for all humankind, wearing the “mark” of Cain. God decrees that no one shall lay a hand upon him so that he cannot be murdered in turn. He persists as a martyr cursed to life as a symbol of the eternal punishment of wrongdoing. While in the coda of The Good Son Cave and The Bad Seeds again chant the line “one more man gone, one more man,” their repetition represents the continued line of murders that follow in Cain’s wake.

A primal surge of red inside and out runs through Cave’s discography, a rich seam of menace and dread, with his deep red shirt on the cover of Tender Prey expressing the bleeding heart of the artist and the blood and violence yet to come. “Jack the Ripper killed women in real life — Nick Cave kills people in his music.” This persistent almost obsessive theme rendered the charge of violent hypersexualized misogyny in Cave’s music more real, right through into the mid-1990s. Cave began his slow descent into tales of murder with The Birthday Party’s Deep in the Woods (1983), the knife unleashed from its sheath to bring chaos; Cave offers the pun from “rags to stitches” carving letters into his victim’s body.

Cave would remember his father reading him the murder scene of Fyodor Dostoyevsky’s 1866 novel Crime and Punishment in which the protagonist Raskolnikov kills two people, escapes undetected, and is haunted by his actions: “When I grew a little older my father read me the murder scene in this book and said: ‘This is what violent literature should be like, son.’ He was right.” Combined with his reading of Lolita we can see sparks flying between twin poles of great literature for Cave, merging into an artistic fascination with the power of life and erasure of death, where procreation and murder dance between two elemental states.

This sheer bloodiness is partly expressed through the twist and turning of love songs, what music critic Anwen Crawford referred to as Cave’s lustmord or “sexual murder” of obsession spilling over into violence. She observes that the character of From Her to Eternity ultimately blames his infatuation with the woman upstairs on her, as an enchanting siren, “nagging me like a shrew.” Where his characters predominantly kill women out of love, an attitude to which Cave would later express some regret, without rejecting his songs, Crawford finds a career built upon a “metaphorical pile of female corpses.”

She writes partially in response to the journalist Peter Conrad, who in his 2009 article The Good Son draws out the exaggerations of Cave’s persona and his continued fascination with murder, while casting a thoughtful critical eye over his use of language. Occasionally Conrad exemplifies the worst kind of fan who buys completely into the wholesale myth of the artist through his songs, himself exhibiting casual misogyny and lazy glorification of real murders referring to the “whore-slaughtering Yorkshire Ripper, Peter Sutcliffe.” In 1988 Cave would already speak with some regret, knowing he had overloaded his misogyny to the point of parody: “I feel that I’ve misrepresented women in my songs, and I’ve actually misrepresented the way I feel about them. I invented a type of woman that I used artistically in order to dump all my ill feelings and suspicions on.” Though this admission would not yield a drastic shift in Cave’s lyrical direction for some years, the solo artist Anna Calvi would see the extremes of his subject matter exposing deeper vulnerability: “He’s honest about the madness of masculinity, showing all the dark corners of it.”

Cave continued the resonance of Cain and Abel’s tale across The Good Son album, but it began with the band name of The Bad Seeds. Mentioned in Cave’s list of beloved books, The Bad Seed is a 1954 novel by American writer William March telling the story of a young girl Rhoda who seems the perfect child, while her mother slowly comes to realize she is a sociopathic killer. A story embodying the biblical warning of the bad apple in the bunch, it seems too good to be true not to be a Cave red herring. The book draws its own title from the parable of the sower from Matthew 13:18–23. The seed that falls on thorny or stony ground, representing a spirit not ready to receive God, will not take root in the heart and flourish. The bad seed either rots or grows crooked, like the thwarted figures of Cave’s songs; it thrives in the margins harboring a deep= enmity for the rest of “straight” society.

Gnashing his teeth again and again at the persistence of evil, Cave pushes our faces up to the ugliest side of human behaviors pitching the question of a fixed human nature where some are “born to be bad”, killers by design and for others to become victims. This sparks the argument for a kind of determinism rather than people being swayed by malign influences. In O’Malley’s Bar, Cave is forced toward a full stop, causing him to wonder plainly on the freewheeling riff of the murderer: “If I have no free will / then how can I be morally culpable?” For all the fatalism that seems to burn through Cave’s songs of death and destruction, he asks whether or not the most extreme suffering might still have meaning, even when it becomes surreal and absurd.

A man walks into a bar called The Bucket of Blood — and kills everyone in the place. From the first trigger pull of Stagger Lee Cave hammers home the song’s punchline, taking the comic book violence of O’Malley’s Bar to new levels of profanity. It began with a white Stetson beaming bright; then stolen, scuffed, spat upon — the mark is made and a line crossed on the lifeline of the offender — from which there is no return. In other versions of the story the hat is already ox-blood red, “the color of cancer,” a warning of what’s to come. The Bad Seeds hammer home a dense piano chord dragged alongside a howl from the gut raked up the spine before Blixa Bargeld’s rock-drill guitar marks a hole driven into the head, then slowing into a reverse shriek as he swallows the mic into his whole mouth, pulling the still whirling drill bit out from the skull, in a helter skelter of blood and gore.

Cave found the original song (thought to originate from 1895) from a book called The Life, the Lore, and Folk Poetry of the Black Hustler, recounting the half-whispered tale of Stack O’Lee or Stagolee. Greil Marcus notes that Cave’s song draws upon the tradition of the prison toast: ritualized declamatory insults become a loose narrative where injury is heaped upon injury; long after the spark of the first insult, they become alternative Americana in the national songbook.

Cave himself becomes the wronged man, growing into the stature of evil as he steps into Stagger Lee’s “rat-drawn shoes” — six feet plus of meanness bound up in a whirlwind of “fucks.” Marcus notes their wild run of obscenities tumbles into a chain of graphically absurd imagery: “not merely an assault on rational discourse but on English itself.” Making a scene as counting coup Lee’s swagger grows in proportion to his ego, Cave noted: “Just like Stagger Lee himself, there seem to be no limits on how evil this song can become.” Stagger fulfills his nature as only the “meanest motherfucker can — he knows no other way to be.”

Recorded as an afterthought to Murder Ballads, the track has the air of novelty that goes full circle back to the sickly sweet tone of Where the Wild Roses Grow. Though between them these two dark stars would come to define the heart of the record, its blacker than black sense of humor, they emerge as genre pieces, nudged toward self-parody. Cave would admit to Stagger Lee as a strike of inspiration, compared to his months-long rate of composition: “I hear people talk about art as being man-made, that it’s about craftsmanship. I think that’s bullshit. The gods gave us this song and they were pissing themselves with laughter when they did it.”

Cave exposes the self-delusion and egotism of many killers who see themselves as existing beyond the realm of normal humanity and above the moral demands of their actions. The narcissistic killer of O’Malley’s Bar only pauses to admire his own reflection in the mirror. This marks him with the rare ability to dissociate from the suffering in other human lives: they are weak, unworthy cattle, inviting their own destruction — the act of murder validates the existence of the killer. Speaking in 1996, Cave said, “I wanted to get the point across of your archetypical nonhuman being that America seems to produce. As well as the situation where these people who have no identity feel that they have to go to such horrendous lengths to get some meaning to their lives. The killer thinks he’s the winged angel of death, but on the other hand, he is, in fact, a moral coward who can’t shoot himself at the end.”

Cave would lean heavily on the murder ballad tradition (as a record of folk history ballooned into legend) where facts are recounted quite plainly, and life is often held cheap, but the essence of tragedy was also shown to be meaningful, tough, sometimes absurd to the tipping point of tragedy into comedy. For some this is hollow laughter, but it bears the hallmarks of a knowing self-consciousness willing to shrug off artistic reputation for making great songs; it becomes a traditional murder ballad as overkill.

In a 1988 interview, a journalist suggests Johnny Cash as the godfather of the murder ballad, citing the immortal line from one of his earliest songs Folsom Prison Blues: “I shot a man in Reno just to watch him die.” Cave responds with palpable enthusiasm to a cold-blooded song first released in 1955 and delivered with renewed enthusiasm as part of the 1968 live album At Folsom Prison performed in front of a crowd of prison inmates, Cave said: “I don’t know how politically correct that line is, but fuck what a line!”

The centerpiece of 1994’s Let Love In album, Red Right Hand begins with someone lighting up a cigarette, like the devil had just stepped onto the soundstage of his own biopic. The song is peppered with creepy organs, theremin, oscillator, timpani, woodblock — throwing every sound-bending mirage into a dusty desert backdrop pitched at the terrible sight of a dark silhouette stepping out from the blood-pitched sun. The stranger wanders into town, which for Cave is really his hometown of Wangaratta, dominated by tough rural work and not much play except a few bars and a haunted roads stretching far beyond the town’s main street — Cave’s own Smokestack Lightning of the mind.

The Red Right Hand legend bears the lightning strike of violence piercing the land with a harbinger’s sense of fear and doom. The color itself is the echo of blood, the abject horror of the insides turned out; confronting the viewer in the light of an open wound, like Jesus pierced by the spear of destiny on the cross. Blood on the hands becomes the aura of guilt; elsewhere trees rise like hands in prayer, the water of life a stain that won’t wash. Cave recalls the knowing cry of Lady Macbeth’s “out damn spot” line as she tries to remove the symbol of her lingering guilt, the echo of a difficult memory — not unlike the mark of Cain. Cave refers again to the shock issue of blood in the vengeful Hand of God from the Carnage album.

Cave himself would luxuriate in the shadow of the bad guy character, always attractive, it offered a new liberty in meanness, a freedom coined by Milton as being: “better to reign in hell, than serve in Heaven”, where thwarted father figures serve as cruel antiheroes becoming victims of patricide, a figure that looms large on several Cave albums. For the love of the murderer, it is from the birth of original sin that humankind is tainted by an innate desire to performatively transgress natural laws; with both the potential to kill, and to be killed. Knowing what this means, evil becomes a verb, to do wrong, rather than to be the personification of a higher metaphorical evil, in the music of Nick Cave this becomes equally as shocking and mundane as the difference between life and death.

Find out more HERE.