Eugene Hütz is more than half an hour late. Which is exactly how it should be.

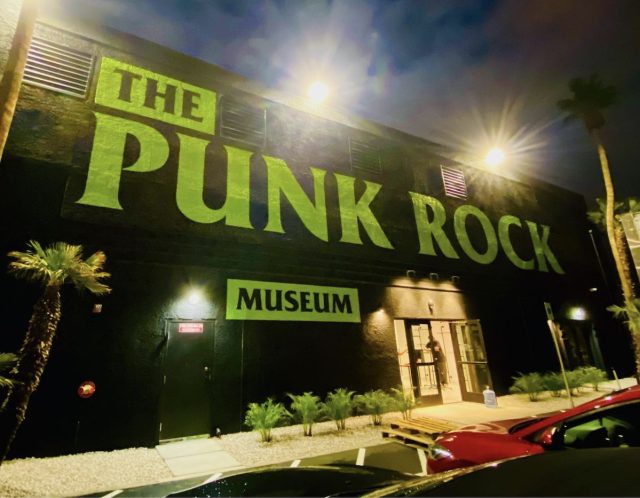

It’s a hot Friday afternoon in Las Vegas, and I’ve just arrived in the lobby / gift shop of the recently opened Punk Rock Museum, housed several blocks north and west of the tourist-laden Strip in an imposing black warehouse adorned with massive lime-green lettering. I’m here to join a group getting a guided tour of the facility from the frontman, founder and chief rabble-rouser of New York gypsy punks Gogol Bordello. But when I check in, I learn that Eugene is (surprise) running behind. He’s still getting his own orientation tour, the staffer explains. He should just be a few more minutes.

On some other day, in some other place, I might be slightly irked by the delay. But not here and not today. If anything, I think I would have been slightly disappointed if Eugene had been standing there waiting for us, all bright-eyed and bushy-tailed, with a Hello, My Name Is… badge on his shirt. Let’s face it: At a museum dedicated to the music of anarchy, chaos and non-conformity, a little light tardiness and a smattering of disorganization feel totally on-brand. Does anybody really expect — or even want — punctuality from punks?

Come to think of it, does the world even need a punk museum? To me, the idea feels kind of contradictory. Oxymoronic. Maybe even hypocritical. Punk was, after all, built around primal elemental forces — destruction and creation, anger and idealism, volume and power, breathtaking speed and perpetual forward motion — and founded on principles of egalitarianism, equality and economy. Collecting, curating and commodifying that for folks to gawp at — after they’ve shelled out $30 for a ticket or $100 for a guided tour by musicians like Hütz — seems like the antithesis or punk. Either that, or it’s the ultimate punk act — Malcolm McLaren’s Great Rock ’N’ Roll Swindle and its ‘cash from chaos’ ethos finally brought to glorious, gleeful fruition amid the nihilistic hedonism of Sin City. But that’s a debate for another day.

Right now, I’m still waiting for Eugene, cooling my heels in the gift shop. It has the usual souvenirs — T-shirts and hoodies, keychains and fridge magnets, postcards and books, even jigsaw puzzles. Most of it is surprisingly affordable. I scope out a few shirts to score later — and bump into behemothic Pennywise frontman Fletcher Dragge, also browsing the merch. That seems like a good sign.

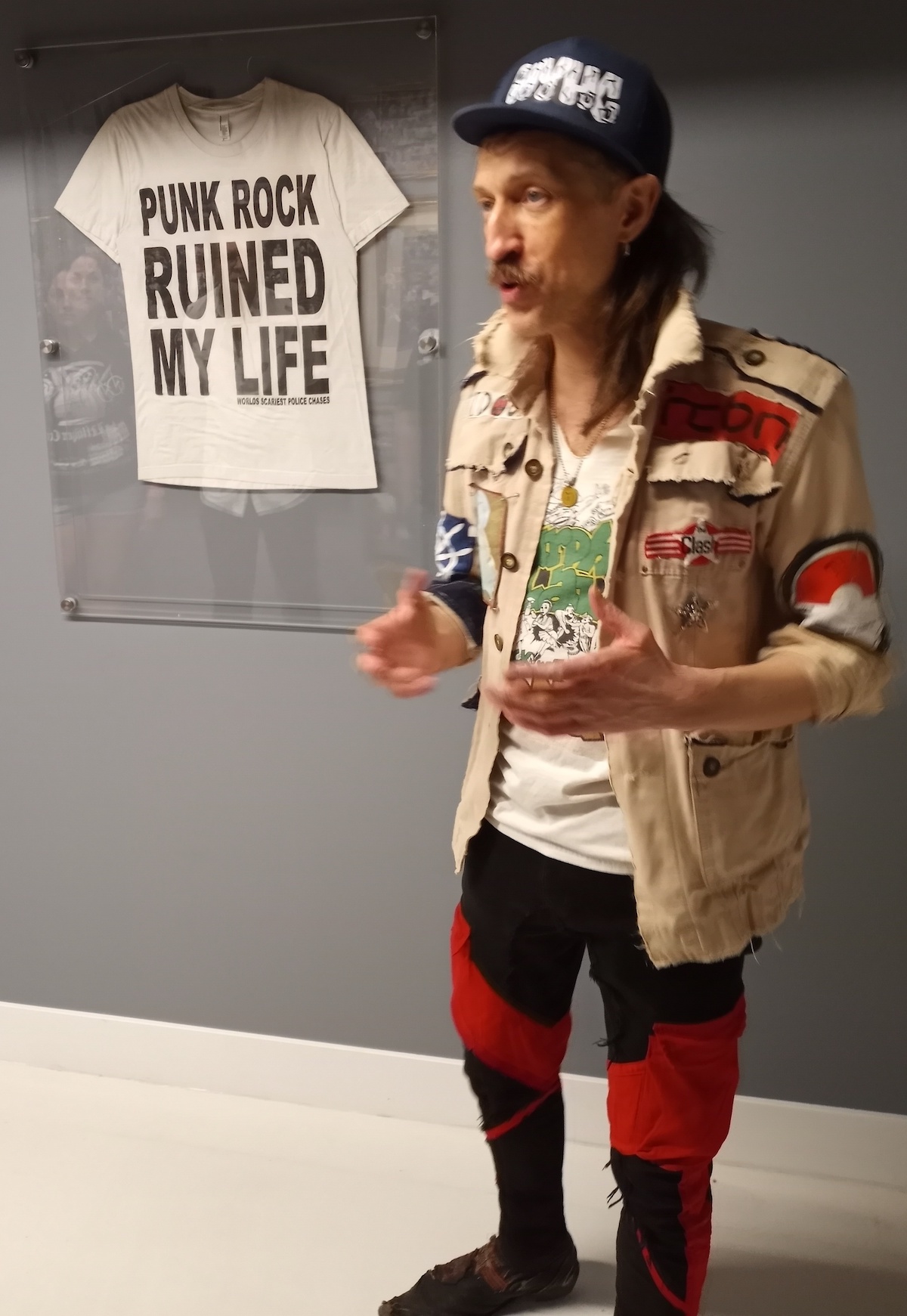

Finally, following some gentle cat-herding by the patient staff — after Eugene finished his orientation, he bellied up to the in-house bar, then went to the parking lot to talk to Fletcher, at which point one of the other members of my tour group went to the bar, and so on — we finally find ourselves in the museum’s entryway, with Eugene at the centre of our small circle. Hütz certainly looks the part. He is sporting skinny black and red pants, a desert-style military jacket and pointy shoes decorated (and perhaps held together) with Clash and Slayer patches. On his head is a ballcap bearing the NYHC logo. In his hand is a cup of what looks like red wine. “Where do we start?” he asks, his head swivelling around to take in the Intro Room’s black-and-white photos of punk icons.

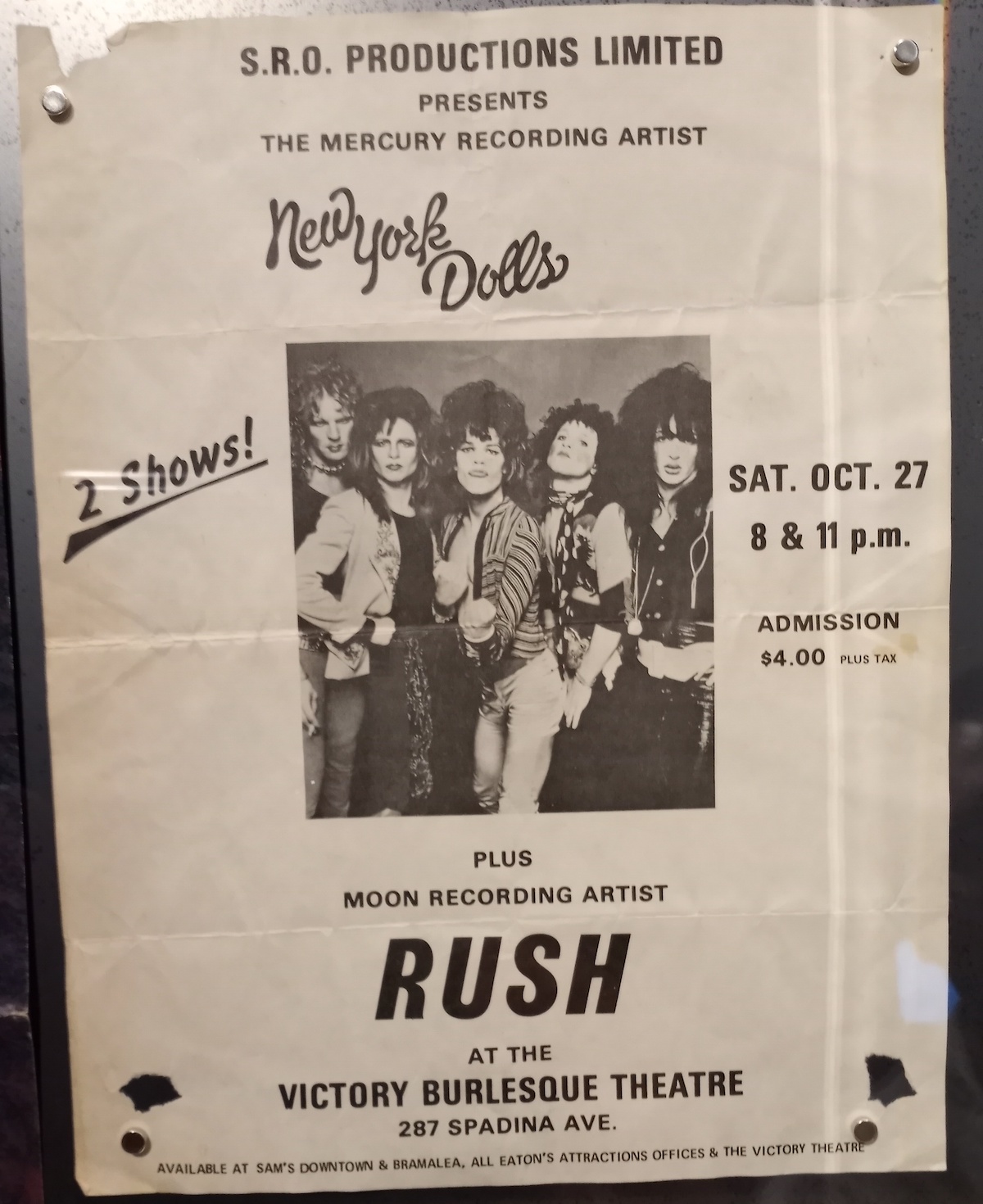

Thankfully, like the seasoned performer he is, Hütz finds his feet once we arrive at the first display cases dedicated to proto-punks like Iggy Pop (“a tremendous influence on everyone in here,” he understates), The New York Dolls (“a very exciting band”) and The Ramones. In the first of many revealing personal anecdotes he shares during our time, Hütz explains how he identifies with drummer Tommy Ramone (real last name Erdelyi), who was born in Hungary and fled to the U.S. with his family during political upheaval, much as Eugene left his native Ukraine to escape the Chernobyl disaster. He feels a similar kinship with late guitarist Ivan Kral (Iggy Pop, Patti Smith), who escaped Czechoslovakia when Russian tanks rolled into Prague.

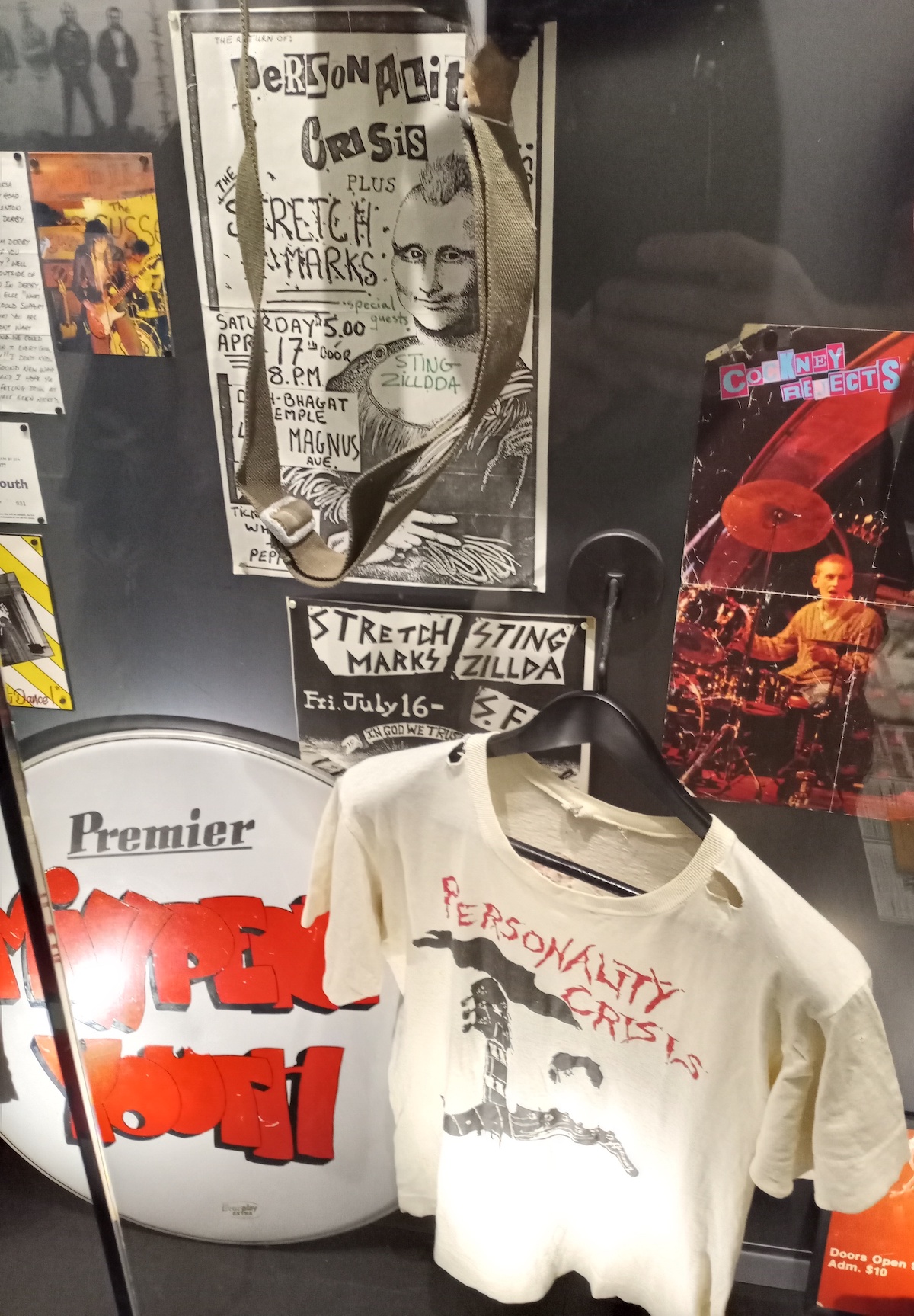

While he discusses these early heroes of punk — and expresses his love for a band I’m surprised to learn he digs, Slade (“they were bascially punk without the politics,” he claims) — I browse display cases crammed with exhibits: Glen Matlock’s Sex Pistols bass, Johnny Thunders’ Les Paul Jr., Dee Dee Ramone’s leather jacket, Joe Strummer’s ‘Brigade Rosse’ shirt as seen in the film Rude Boy, a pink-and-black sweater worn by Captain Sensible of The Damned and plenty more, all crammed in along with gig flyers, lyric sheets, posters, etc.

Like any lifelong music geek, I’m suitably impressed. I honestly didn’t anticipate how many recognizable, historic punk artifacts the museum would have. And according to co-founder Fat Mike of NOFX, there’s plenty more where they came from. “We already need a bigger boat,” he told me during our recent interview, and I can see he wasn’t kidding. I’ve been to the Rock And Roll Hall Of Fame in Cleveland and the Country Music Hall Of Fame And Museum in Nashville, and this is their equal when it comes to the quantity and quality of the displays. Plus, far as I know, those venues don’t have artists giving tours.

And even if they did, I doubt they would be as interesting as Eugene. I thought he might be glib or flip about the whole thing, but he’s taking this gig seriously. And he knows his shit. While he leads our little gang through the myriad rooms and exhibits — some are in chronological order, while others are devoted to specific cities / scenes or musical subgenres, with appropriate music piped into each area — Hütz speaks with authority, enthusiasm and insight, connecting Black Flag to Bauhaus, or musing on what people must have thought when they first heard Nick Cave’s early band The Birthday Party (“This is coming straight from outer space!”).

For his part, Hütz had no trouble relating to punk, he explains. “Their angst was coming from a real place. And I know that place.” To the young refugee, the scene offered accessibility and connection. “It was about more than music. It was about finding your own tribe … These were bands I could go and see and then meet,” he says, looking at a picture of N.Y.C.hardcore outfit Agnostic Front. “Why do I need to go see David Bowie? I don’t give a fuck about him. But (Roger Miret) was just as charismatic, and I could go watch him and then hang out with him.”

Moving on to a display of D.C. punk fare, Hütz recalls sending a letter to Ian MacKaye of Minor Threat and Fugazi, naively applying for a job with his DIY label Dischord Records. “Three weeks later, I get a letter back saying, ‘We’re not really that kind of record company’,” Eugene says with a chuckle. “But they sent me six or seven CDs and albums that had just come out, which I thought was really cool. And last time I talked to Ian MacKaye, he said he’s going to find that letter, because he keeps everything. So maybe you’ll see that here someday.”

Hütz also reminisces about sending recordings from his pre-Gogol Bordello band The Fags to Fat Mike’s Fat Wreck label, whose snarky, form-letter rejection missive is also on display. “I got a polite, funny, fuck-off from Fat Mike,” Eugene recalls. “I thought, ‘I’m moving up in the world.’ ” Another hero he encountered: Jello Biafra, who he calls “amazing, eccentric and totally righteous.” Standing in front of some Jello memorabilia, Hütz remembers when the Dead Kennedys frontman came to see Gogol Bordello, saying frankly that if he didn’t like the show, he wouldn’t stay. He not only stayed, Hütz says; he and Biafra ended up talking until sunrise, sparking a friendship that continues to this day. In fact, the two just collaborated on a benefit single for Ukraine.

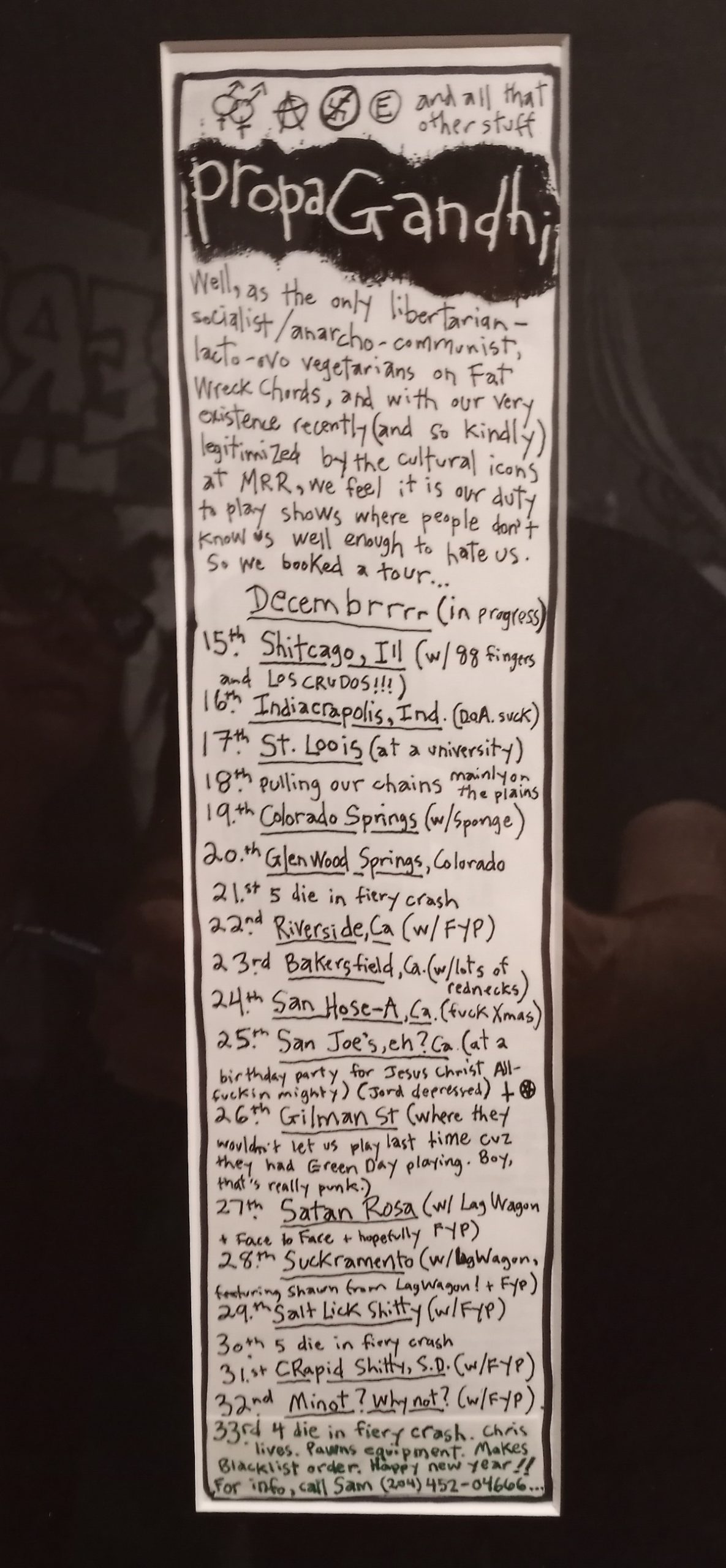

As we shuffle along through the displays, I keep expecting to come to the end of the line. But there’s always another room, another case, another cool piece of memorabilia. From a display of Maximum Rocknroll magazines (“My New York Times,” Hutz says) to Kurt Cobain’s leather jacket and Nirvana’s Grammy for MTV Unplugged — and even the wooden molds used to make Devo’s red plastic Energy Domes — there’s so much stuff here I give up trying to catalogue it all. There’s a Canadian section highlighting D.O.A., SNFU, Personality Crisis, Propagandhi and Stretch Marks — with Teenage Head’s Let’s Shake pumping out of the sound system. There’s even a full-scale recreation of Pennywise’s garage practice space, which I would have loved to ask Fletcher about. Some of punk’s more notorious characters are even represented. Eugene praises Wendy O. Williams of The Plasmastics as someone “who performed her own stunts with no double.” He even has a soft spot for notorious degenerate GG Allin, calling him “very gifted” in his early work. “Later something happened,” Eugene quips. “I don’t know what; I’m not a psychiatrist.”

When we finally reach the end of the main-floor displays, I think we’re done. But Eugene leads us through the adjoining bar and up the stairs — past the mezzanine-level chapel for weddings and wakes — to the second floor, which features the venue’s jam room, another sort of musical chapel where you can play Tim Armstrong’s old pink Hagstrom, one of Fat Mike’s basses, and a slew of other instruments used by Pennywise, TSOL and others. Mike has told me Lemmy’s Rickenbacker bass and Marshall stack will be arriving soon. We all eye the instruments, but no one has the stones to strap one on and strum a few chords.

Outside the jam room are still more displays, including superb photo exhibits by punk photographers Rikki Ercoli and Angela Boatwright — and a collection that finally stumps Hutz: pop-punk. “I don’t know anything about that,” he admits. “I’d have to Shazam it.” No worries, dude. Truth is, I’m good. More than, frankly. We’ve all been treading the venue’s cracked concrete floors for nearly two hours now; Eugene is already late for his next tour, and the same staffers that were trying to collar him earlier are starting to hover again.

Like any rock star worth his stripes, he seems not to notice or care. As he surveys a wall of tour photos and the facility’s Outro Room — featuring more giant B&W portraits — he begins to wax philosophical. “It’s not easy,” he says. “It’s cliche to say punk is a way of life, but it is. And it’s a pretty good way of life. If you have a positive disposition, it can be a good thing. But if you have a negative one, it can kill you.”

Although Eugene seems ready to hang out indefinitely, that seems like a good exit line to me. I say goodbye, tell him I look forward to seeing him on his Canadian tour this summer — he seems vaguely surprised to learn he’s coming here — and head down to the gift shop to bag some shirts. As I wait outside for my Uber, Hütz makes an encore appearance: He walks out the front door, shoots me a salute, says farewell again, and heads off down the street, looking at his phone. The next tour can wait.

Which is exactly how it should be.