THE EDITED PRESS RELEASE: “We had a joke in the studio,” says Nick Waterhouse. “Some of the guys were like, ‘Nick, you’re gonna end up at a press conference like Dylan in ’65: ‘Who’s The Fooler?’ ‘I don’t know, man, maybe it’s you! Maybe it’s me. Maybe I’m becoming The Fooler right now … ’”

The title of the sixth album from the Californian singer-songwriter is more than just the name of one of its dozen immaculate tracks. The Fooler is both a clue and a red herring. The Fooler is the observed and the observer, narrator and subject, truth and lie. The Fooler is the shadow and reflection of a city the artist knows sufficiently well to wander with his eyes closed, and a place which very possibly never even existed. The Fooler is not so much an unreliable narrator as a constantly shifting perspective. The Fooler is the new album by Nick Waterhouse, and it’s a lot.

“Many of the stories in the record come from that feeling of plasticity,” says Waterhouse. “What is memory? What is time? What is love between two human beings like in this imaginary city? It’s Cubist. A listener sees the angles of my life — and inexorably, my career — reflected in this work from all sides at once. I started thinking again about my university days, about modernist writers like Virginia Woolf, Christopher Isherwood, Hart Crane, or Ford Maddox Ford; about memory and how it betrays you; what you can see and what you can’t.”

Recorded by Mark Neill in Valdosta, Georgia, the album is a song cycle of sorts, the arc of the album telling a tale of a city and its denizens. “There’s a phase shift that occurred writing this record,” says Waterhouse. “I had a breakthrough in how to tell stories in songs. It’s like an epiphany. I started realizing how I could bend time in these words and a lot of the things that weave through the record. I have a perspective as a narrator now, instead of being the occupant of the songs.”

Waterhouse is a modern American singer-songwriter who released his debut album Time’s All Gone in 2012. In his music you will hear echoes of things you might think you know, or believe you remember, filtered through the lens of a unique artistic perspective. You will hear rhythm and blues, garage rock, radio soul and wee-small-hours balladry — but reconfigured, made new. In Waterhouse’s music, the time is both now and then. The past is the present is the future. The sound is classic yet unclassifiable. “I actually find it very fascinating,” he says. “I’m like, Where did this come from? Especially during this record, I started just becoming what Allen Ginsburg called a pure breath. I was becoming pure breath with my ideas.”

His last record, Promenade Blue (2021), was lushly orchestrated and widely acclaimed. Since then things have moved on — and fast. Waterhouse has relocated from California to France, ended a long-term relationship, and hit upon an exciting new creative impetus. The sense right now is of a vortex whirring.

“The last tour I did was, in some ways, the most successful tour I’ve ever had, but it was a paper tiger,” he says. “We finished it and my inner compass said, We’re going to continue performing this, I’m going to live in this Promenade Blue world for a year — and that just isn’t how it works.” Cue The Fooler, messing with the narrative. “Instead, the pendulum swung hard in the other direction. It was not intentional. It really shook me how much of a punctuation Promenade Blue actually felt like. I was shutting a door with that, I did everything I could with that world. Now, we’re into this other sonic world.”

The Fooler is partly a farewell to, and reclamation of, a version of Waterhouse’s past existence framed by a city that is part dream, part reality and part potential. “I had this whole life in San Francisco, and a lot of that city changed and dissipated and was levelled by, let’s be honest, money. In several years it was like somebody cut off the oxygen there. It really did happen, and it was sad for me. A lot of what I wanted out of life was there. I went through processing a lot of that over the years.”

Matters reached a head on a return visit to see an old friend during the COVID lockdown. “It was during a particularly peak experience, walking a street in San Francisco so surreally empty it felt like a dream, that The Fooler began to occur. The city had been somewhere I physically and emotionally had left some time before, and now it felt like Pompeii. The physical abandonment finally mirrored my internal image of the place; a vacant stage where things had played out so vibrantly at one time. This street in the city looked exactly the same in mid-day as it had at midnight, so long ago. I had already let go, but this was an even more physical manifestation of: Wow, this is all gone.”

Following that existential epiphany, The Fooler came quickly into view. Discussing the stellar title track, Waterhouse says: “It’s about how your own heart and your memories can betray you in really nice ways. The rest of the songs were all orbiting around that. It was like, Wow, I’m writing my city record. It’s a parting shot, but to a place that was already gone. And now it’s this record. I find that to be deeply moving and satisfying.”

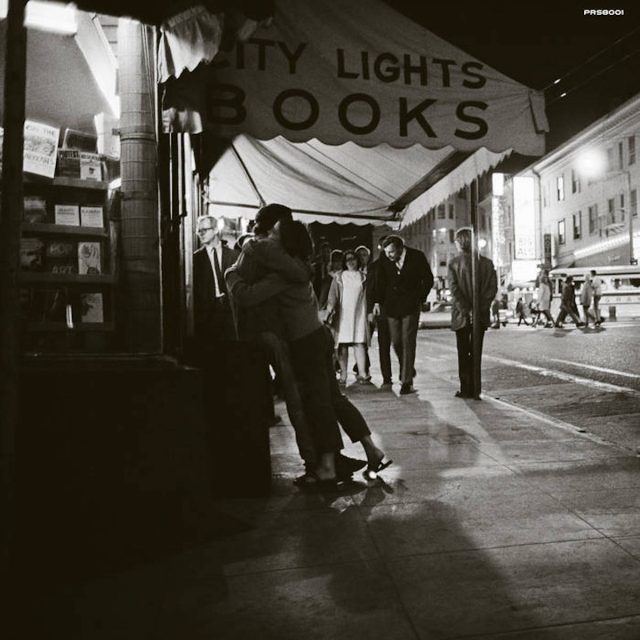

The beautiful black and white image on the album cover captures the mise-en-scène. It’s a previously unpublished photograph by the late, great photojournalist Jim Marshall of the legendary City Lights bookstore in San Francisco’s North Beach. Waterhouse used to live around the corner. “My local bars, Tosca and Specs, were directly across from City Lights. All of this life that I had was on that corner of Broadway and Columbus. There’s a lot of time slip, because that could have been me and my friends in that photo.” A pause. “Maybe I’m in there. I don’t know.”

The Fooler was recorded in Mark Neill’s studio, Soil Of The South, in the small town of Valdosta, Georgia, with a small crew of musicians. A former room in a ballet school, Soil Of The South is in the great tradition of American studios such as Chess and Sun. “Not the place that looks like a spaceship, but more like the place that looks like a dentist office in 1965,” says Waterhouse. “It can hold five people comfortably, but not more.” They tracked the record fast, in four or five days near the end of 2021. A further handful of days for overdubs and mixing early in 2022 and the record was finished.

The journey to Valdosta had begun, unbeknown to all, with the virtual gatherings Waterhouse convened on Instagram, which became an informal radio show of sorts. “I was thinking back to being at the record shop in San Francisco where people would come and make drinks on Friday after work, and we’d play records for each other. I started playing 45s on my Instagram Live, making drinks and talking about them. A lot of people were tuning in, and it meant a lot of people re-entered my life.”

One such person was Mark Neill. A lodestar of the west coast post-punk scene turned master of sound design, Neill is perhaps best known for earning a Grammy for his work on The Black Keys’ album Brothers. “Mark has known about me for 20-odd years, and has always wanted to work with me,” says Waterhouse. “He’s a real phone guy, so he’d call me up. I wasn’t even looking to make a record out of those conversations. We were discussing the psychological geography of a lot of the records that shaped a time in my life, and shaped me now and in the future.”

The sound of The Fooler is the sound of this city haunted by song. A place filled with 45s produced by people like Bert Berns or released on Scepter, Wand, Atlantic and Verve and heard on the jukeboxes in North Beach. “The sound was the speaker over the record shop door in Lower Haight, or the sound systems of Mission and downtown and Tenderloin bars,” says Waterhouse. “Or the sound of the laptop playing The Velvet Underground bootleg, the one where the guy keeps ordering the Pernod, or Roy Orbison in concert, with the lover pretending she wasn’t crying as she vacuumed the apartment; or crying as she locked herself in the bathroom of a matchbox-sized Chinatown apartment. It’s about how time slips between the times when these influences were recorded and my own life was lived in the moment.”

Neill, it turns out, proved a perfect foil for the concept of The Fooler. He plays tricks with time and space to create a sound that can’t quite be defined. “Mark is one of the last American producer/engineers who’s truly connected to the audio tradition,” says Waterhouse. “Making this record was like going to see the kung fu master on the mountain. You can probably draw a through line from my very first record to this one, but this is something else entirely. The sonic landscape Mark designed is so much further into space, with reverb and depth. The record is in mono and it feels so lush.”

For the first time, Waterhouse relinquished a degree of control in the studio. He was content just to be The Artist. “I wasn’t going to be the producer, or come in with mapped-out arrangement concepts. I could just be, as Mark said, the punk in the mohair sweater; the guy who comes in with a guitar and plays something and he says, Wow, you’ve got to do that! He was very encouraging. A lot of his instincts were to steer me, not necessarily in the opposite direction of where I typically go with a piece of material, but I was making myself so open minded that I was like, ‘Oh, I would normally do this hard when he wants it softer. I would sing it low but he wants it higher.’ Nothing was hard baked, everything was so fragile. It was almost like a French New Wave approach to having these imperfections.”

The result is a record that offers up new riches and fresh perspectives with every spin. The Fooler is studded with highlights. From the hidden corners of Hide & Seek and the roadhouse soul of Play To Win to the primitive, attitudinal, chugging two-chord thrill of Late In The Garden, it builds inexorably to the drama of the title track and pulsing roll ’n’ rock of the final pay off, Unreal, Immaterial. Play it once and it sounds immediately like a collection of great songs. Play it again — and you will — and it feels like a novel or a film slowly unveiling its secrets, kaleidoscopic in its narrative complexity.

Since making the album and making his moves, Waterhouse feels loose and liberated. The Fooler’s spirit of flux has become a guiding principle. “Being in that new state, I think, made me malleable and free. I’m trying to be instinctive about doing this.” He laughs. “And, you know, it’s getting me into all kinds of interesting situations.”