THE EDITED PRESS RELEASE: “Rock ’n’ roll is often hard to define, or even to find, in these fractured musical times. But to paraphrase an old saying, you know it when you hear it.

And you always hear it with The Wallflowers. For the past 30 years, the Jakob Dylan-led act has stood as one of rock’s most dynamic and purposeful bands — a unit dedicated to and continually honing a sound that meshes timeless songwriting and storytelling with a hard-hitting and decidedly modern musical attack. That signature style has been present through the decades, baked into the grooves of smash hits like 1996’s Bringing Down The Horse as well as more recent and exploratory fare like 2012’s Glad All Over.

Even so, in recent years, Dylan — The Wallflowers’ founding singer, songwriter and guitarist — has repeatedly stepped outside of his band, first with a pair of more acoustic and rootsy records, 2008’s Seeing Things and 2010’s Women + Country, and then with the 2018 film Echo In The Canyon and the accompanying soundtrack, which saw him collaborate with a host of artists classic and contemporary, from Neil Young and Eric Clapton to Beck and Fiona Apple. But while it’s been nine long years since we’ve heard from the group with whom he first made his mark, The Wallflowers are silent no more. And Dylan always knew they’d return. “The Wallflowers is much of my life’s work,” he says simply. Plus, he adds with a laugh, “It’s pretty hard to get a good band name, so if you have one, keep it.”

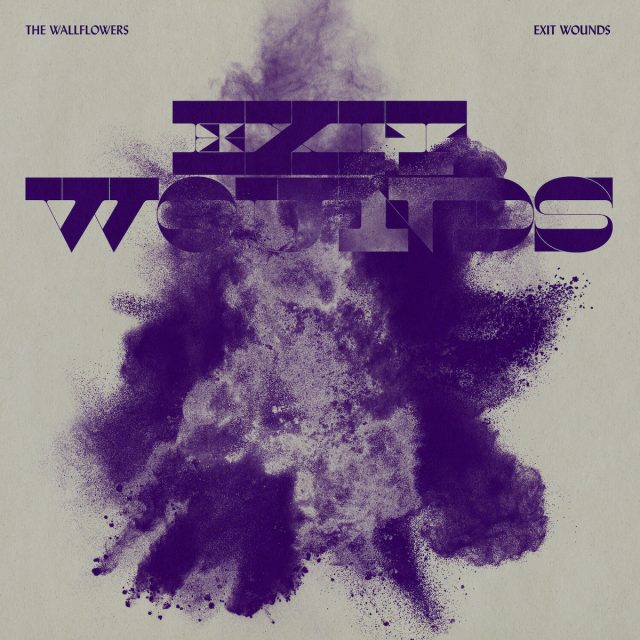

Good band name aside, that life’s work continues with Exit Wounds, the new Wallflowers studio offering. The collection is their first new material since Glad All Over. And while the wait has been long, the record finds the band’s signature sound — lean, potent and eminently entrancing — intact, even as Dylan surrounds himself with a fresh cast of musicians. Which, the frontman is quick to point out, is not all that unusual. “The Wallflowers has always been a vehicle for me to make great rock ’n’ roll records,” he says. “And sometimes the lineup that makes the record transfers over into touring, and sometimes it doesn’t. But my intention is always to make the Wallflowers record I want to make, using the musicians I have beside me.”

Dylan’s vision has always been the core of The Wallflowers’ music. How he chooses to express that vision, however, is what makes a song a Wallflowers song. “I usually just let the songs tell me what kind of arrangements they need,” he says. “And if they’re asking for full-band electric arrangements, then that’s what The Wallflowers provide. And I knew I wanted to make a full-band electric record this time out.” And made one he has, with one special guest on board — Shelby Lynne, who lends her voice to three of the album’s tracks. “I hadn’t met Shelby before, but like most people, I’ve been a fan of hers for quite some time,” Dylan says. “She has one of those voices that’s very uncommon, very unique, very rare.” But there was more to their duet than just a mutual appreciation. “You can have your favorite singer come in, but it doesn’t mean you’ll have any connection — there has to be more than that,” Dylan continues. “And as soon as I heard Shelby sing, I knew we had something.”

That “something” is present throughout Exit Wounds, which, true to its title, is an ode to people — individual and collective — that have, to put it mildly, been through some stuff. “I think everybody — no matter what side of the aisle you’re on — wherever we’re going to next, we’re all taking a lot of exit wounds with us,” Dylan says. “Nobody is the same as they were four years ago. That, to me, is what Exit Wounds signifies. And it’s not meant to be negative at all. It just means that wherever you’re headed, even if it’s to a better place, you leave people and things behind, and you think about those people and those things and you carry them with you. Those are your exit wounds. And right now, we’re all swimming in them.”

To be sure, Exit Wounds is populated by scarred souls that “used to rumble, used to roar,” of “nobodies drinking flat beer,” and those who’ve been “abandoned and locked out and pressed to the fire.” Throughout, Dylan’s lyrics are specked with images of spears and swords and battle-worn flags being raised, of wayward buses and battered ships, riderless horses and lost planes. Of course, ask Dylan what these songs are about, and, well, like most practised songwriters, he’s not going to tell you. “I’m always a little cautious when people ask that,” he says. “Not because it demystifies the songs, but more because I think it’s belittling to the listener to have to be ‘told.’ I usually find that if you have to do that for someone, you probably didn’t hit your mark.”

That said, Dylan will at least acknowledge that the tracks on Exit Wounds reflect the tumultuous times in which they were written. “The climate affects how you feel, which affects how you’re writing songs, even if you’re not writing specifically about current events.” He turns to the late John Prine to illustrate his point. “If we still had John Prine, I don’t think he’d be writing songs specifically about current affairs, but he’d probably be writing songs about characters affected by current affairs. I think that’s mostly what I do. I’m the same writer I’ve always been — I was just also writing during a time when the world felt like it was falling apart. That changes the way you address even the simplest things, because you have panic in your mind all the time. You have anxiety. And you also have hope. And it’s all in there.”

When it came to realizing these new songs on record, Dylan assembled a backing band of musical associates — “people that I’ve wanted to play with or that I have played with through the years” — and headed into the studio under the watchful eye of producer Butch Walker. Beyond Walker’s pedigree as an in-demand producer and first-rate singer-songwriter and musician, he’s also, Dylan says, “someone I’ve known a long time, and that was important to me. Because you go through a lot when you make records, to be honest. When you’re young, you’re taught that if you don’t have conflict in the studio, then you’re probably not doing anything good. But I don’t believe that. And so it was more of a joyful experience making this record.”

That joyful experience extended to Dylan’s interplay with his fellow musicians. “This was not the type of thing where it’s a rotating cast and you call a different drummer for each song, or you pull out the Rolodex and ring the local sessions guys,” Dylan says. “The record was made as a band — the five Wallflowers.” And to Dylan, a band, even one with a constantly shifting lineup, is a sacred thing. “I’ve always been a believer in collaboration,” he says, “and no matter who I’m playing with I’ve always tried to include them very heavily. Otherwise, why would they be around? Because I do think bands, whether it’s a long standing group or just five people who are working together for that one stretch of time, make better rock ‘n’ roll records than solo artists.” He laughs. “I mean, it’s not 100 percent true, but it’s usually true.” At the end of the day, Dylan continues, “It’s just exciting to have guys playing in a room together. That’s how you get the one plus one equals three factor, you know? That’s the magic.”

For Dylan, Exit Wounds is the next chapter in a career devoted to chasing — and capturing — that magic. “I came up in an era of great rock ’n’ roll bands making great music, and it’s the way I always imagined I would do it one day,” he says. “So that’s always been my vision with The Wallflowers — to be a great rock ’n’ roll band. And I’ve worked on it for 30 years now and I still have a lot to say. It’s something I started a long time ago, and it’s far from finished.”