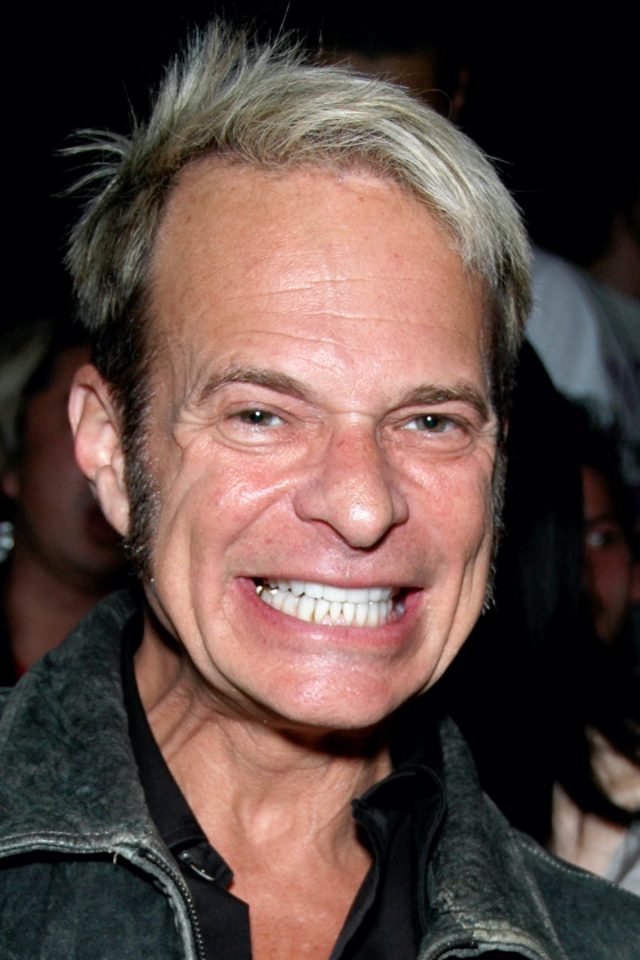

When Van Halen regrouped (more or less) in 2012 and released the comeback album A Different Kind of Truth, frontman David Lee Roth apparently did just two print interviews. One was with the L.A. Times, his hometown paper. The other was with me, during my days as national music critic for a Canadian newspaper chain. (Believe me, I have no idea how the hell that happened either.) I knew going in it would not be a cakewalk; Roth has always been a slippery customer who basically ignores journalist’s questions and just delivers rambling monologues from his hotwired pinball machine of a brain. True to form, the legendary motorouth spat out more than 4,000 words during our 30-minute chat, unleashing a torrent of metaphysical mumbo-jumbo, blatant boasting, random digressions and bizarre one-liners. There was no way it could run as a regular Q&A. So I cherry-picked as many relevant and entertaining quotes as I could fit on two newspaper pages, and left the rest in the hard drive. Until now. Given the death of Eddie Van Halen on Tuesday, I can think of no better excuse to run our conversation in full for the first time. Here’s the complete, unexpurgated transcript. Buckle up:

You literally waited half a lifetime to make a new Van Halen album. Were you surprised it took this long — or surprised it happened at all?

Well, the tale of Van Halen is as long and storied and left-turning as anyone, with plenty of ups and downs and twist and turns and stories going back and forth. But that’s the story of every colourful artist ever. Nobody well-adjusted ever got my job, much less kept it this long. But the band has stayed together. You know, if we take it out of the personal and think of our favourite jazz musicians, we never blinked when their organizations or confabs only lasted perhaps an album or two, because the personalities were as incendiary as the music. And though Van Halen’s history is incandescent and full of allegations— most of them true — we’ve taken the music very seriously. Starting from when we were classically trained kids. Yeah, everybody took a class in piano two days a week after school. But we were brought to music in a very different fashion. We did it five days a week after school with professional tutors. The Van Halens competed in piano competitions and used the money for rent when they came to the United States. And my two cousins Peter and Pearl Zukovsky were first and second clarinet chair with the L.A. Philharmonic. So when I started, it wasn’t a terribly friendly atmosphere. It was Eastern European. It was very unforgiving. And up to this minute, our work ethic is the antithesis of what common rock ’n’ roll would be. The mise en scene — which is about as much French as I can actually spell — the ambient qualities, the intangibles of Van Halen contradict the way that you have to carry on in order to deliver that vibe reliably. We’ve been rehearsing for the last three months, frequently at nine and 10 in the morning.

That’s a very un-rock hour to be up and working.

It’s spec-ops — special ops — in that it doesn’t matter what time it is. We do it at 9 because that’s the time when we are called upon to play.

After so many years of musical divorce, is this reunion a rekindled romance or a marriage of convenience?

We never left. We operated individually. And the ensemble would get together periodically. But this kind of a contribution to the overall community will remand itself to the very first sentence of our obituaries. It goes beyond the past. Look into the future. This material will be around, with all the new technology, for hundreds of years. Because people don’t change. The plain of emotions that Van Halen solicits and compels is permanent. You don’t need to speak English to understand what I’m singing about. You don’t need to be a rock ’n’ roll fan to love and appreciate the show. You don’t even need to have hearing. Our deaf section is routinely filled. Consequently, it transcends neighbourhoods. It’s international.

The game has changed a lot since you’ve been away. Where does Van Halen fit in today’s world? What’s your role?

There’s no role. There are 45 channels on satellite alone that Van Halen occupies. There are many more neighbourhoods now than we used to play that compel the music that we’ve composed. For example, the Venice Beach surf community here in Southern California is very different from the south-of-the-harbour freeway, Snoop–Doggie-lowrider community. And in one sense of the word, you’ll have something like Runnin’ With the Devil for the Zephyr skate team. And we’re the ones who sold you Ricky Ricardo rumba for Jamie’s Cryin’ — and Dance The Night Away, for that matter. That’s pure Carlos Santana. That’s ‘You gotta change your Evil Ways,’ which we used to play three times a night, depending on which neighbourhood we were involved in. Those neighbourhoods, once again, only expand. What’s more expansive than Spanish speaking? I speak fluent Spanish. I can get us totally in trouble now in Spanish and Portuguese. And it’s in our music. If you are guitar-centric, if you’re batteria drum-centric, you’re telling me you don’t know Van Halen? You know, my father was a prison doctor for the last 25 years of his career. We called it the Ivy League — Folsom, Quentin. And he used to joke: When one of our records would come out, both the guards and the inmates celebrated. If you carry a gun to work, whether it’s with a uniform or a pair of two-tone shoes, you telling me you don’t know me? Come on, loco! And those occupations are forever, esse! That’s where Van Halen fits. For example, we picked Kool And The Gang to open for us.

I wanted to ask why you did that.

Because Kool And The Gang and Van Halen, between the years da-da-da and da-da-da, are the sounds of an entire continent at recreation, using its imagination. I think we’ve come to represent that. Although you’re more likely to hear Kool And The Gang at a bar mitzvah than me, even though I’m a brother. You can go a Hasidic Jewish bar mitzvah and they’ll play Ladies’ Night by Kool. Me, they’ll let in because I’m a brother. ‘But he doesn’t sing; he runs with the Devil.’

A Different Kind of Truth is kind of a new album and kind of an old album. Tell me about the idea behind resurrecting and reworking material from the vault as opposed to starting from a clean slate.

OK, that’s a great question. The material was written primarily by Edward and I, as most of Roth-era Van Halen material. Eddie and I work out the changes together and then I go about my merry way with the lyrics. I’ve gotta say, more often than not, those lyrics are written way in advance of the appearance of any musical chord changes. The material that we have pulled from the vault is every bit as much a product of, ‘Who was the disc jockey on the radio? What was your haircut like? What kind of shoes were you wearing? Was that your car or did you borrow the keys to your parents’ car? What was your girlfriend’s name? Did she know about your other girlfriend?’ All of the answers to those questions are what accounts to the music. All music is autobiographic, particularly when it’s not meant to be. It sounds more poignant now than perhaps before because of how it sits in contrast to what modern rock music is perhaps created in — you’re gonna have a fun time editing this. It is by contrast to the way that modern rock music is created that it stands out most. it’s not music that could be created through the means of production. There’s no Pro Tools involved there. there’s no AutoTuning. It’s clearly music that was written before the band got ahold of it. It’s not done, for example, the way U2 would do it. The band in that context get together in the studio and they create together a sort of — I don’t know, it’s kind of a meditation, a mantra, a mutual mantra. It’s beautiful work. Van Halen’s exactly the opposite. We do it 1930s style or old Motown style: Work it until it’s off-book — that’s an old theatre term which means you no longer have to look at the script; there’s no question what’s next in the song, what’s the next word — and then go into the studio and perform it as an act of emotional content. and Hopefully it is — what do the Japanese call it? The formless form! Mushin. No mind.

But you know you’re going to get flack from people who are going to look at all these old songs and say that it proves the well is dry.

No, it proves that they are of short vision if that’s truly what they think. I wasn’t done with my answer. I retooled all of the verses and melodies. I retooled all of the lyrics. And to my memory, most people don’t go home humming chord changes. They don’t go home from a concert humming the light show. And they don’t go home, singing to each other in the pickup truck, the album cover. So there is a body of new that meets halfway there that I think makes very colourful sense. The idea that it was in a vault depends: Are you talking about a head of lettuce or fine wine, sir? Perhaps age has dignified it even further by virtue of its authenticity. That’s it! It’s authentic music that was written in the lab, so to speak. It wasn’t jammed into existence. It was authored. It was composed. Perhaps Shakespeare is mo’ modern than ever before.

If that’s the case, why did you choose to rewrite the lyrics?

Well, you have to have a story to tell. That’s why there are no idiot savants in authorship, in journalism. There are no child savants in reportage or poetry. Because you have to have a story to tell. You don’t have to have a story in order to act out emotion through music instrumentally. Consequently, we have a lot of very young players who can comport some emotional content and can play very fast. I remember growing up and seeing The Ed Sullivan Show — every year there was some new boy who could play Rachmaninoff twice as fast as the last fellow. We see that in all kinds of music, whether it’s Brad Paisley or Yngwie Malmsteen or anybody halfway between those two time indexes. The story changes. My story alone in the last 10 years has been dynamical. One for the books, like my mom would say. Whenever something interesting of colourful or calamitous would happen, the ultimate would be, ‘This one goes in the book,’ as if you were living a book. If you wrote a book about your life, would anybody else be interested? I ask myself that question sometimes. And my capacity to also write, I would like to think, has considerably improved. And I don’t know that that’s the same for an instrumentalist. I don’t know that instrumentalists expand the way we do in the humanities. Does a musician constantly expand his vocabulary? Does a musician constantly come away with rethinking a storyline? For example, (the song) Tattoo examines at least four or five different approaches to that singular art form alone. There’s a union tattoo or a coal tattoo that we deal with there. There is the mousewife who turns into a momshell — even though she got the tramp stamp, it looks like a branding iron, a misfire, but it had a cathartic influence on her. And easily two-thirds of every customer of all tattoo salons internationally now are women. We deal with ‘better to see these true colours than deal with one of those false virtues.’ Whoa, whoa; no metaphysics before happy hour. And we haven’t even gotten to the actual graphic of it. There’s a lot of food for thought there. I would hope that though we may deal with a lot of the same subjects, we can bring a kind of finesse to it — and not without humour — as we wade through our newfound vision. It’s not an F-ing civics lesson.

That begs the question of how well you can still relate to the old songs and lyrics — and the guy who wrote them.

You’re making an assumption. Struggling to cling to the past, you can only get worse. We know the artists who struggle to stay the same. Even that becomes more entertaining than the actual staying the same — the desperation. And if you intend to stay young forever, isn’t that something you can only get worse at day by day? Sounds like an obsession if your struggle is to remain the same. Sounds very strictured. Not very art-centric at all. That sounds like product management to me. Not our design at all. Indeed, we design everything ourselves. I did the album cover, the inner sleeve, the stage design. And I don’t mean I sat down with a stage designer and said, ‘OK, show me some pictures.’ I went down to the stage design company and laid it out on the grids. You’ll find that in every facet of what we do. So I think we’ve expanded into what the digital universe has to offer superbly here. What is the Internet from the fine-arts standpoint but a grand stage? It’s our own radio station, it’s our own magazine, it’s our own television channel. We’ve expanded into that to a degree that — i don’t know, who else is doing this now? Gaga? she’s completely art-centric. She’s got her fist in the mix in virtually every department of what she’s doing there. Who else is doing this? Perhaps U2, I think, are thoroughly involved. They’re literally sitting in front of the monitor in the editing bay, so to speak.

You’re heading out on the road again. How is that experience different than the old days?

We don’t pay any attention to ‘back in the day.’ I think the optimal is to be able to do what you promised to do from top to bottom in a Motown fashion. Can you sing the whole song? Is it recordable quality? My mom can hit the notes. Can you do it with authority? Night after night? And can you really do what people expect and what people think you are about? Or did you have to AutoTune it? Did you have to put a whole lotta tinsel on the tree and utilize a whole lotta production value and a lot of troupe dancers and a variety of diversionary, result-oriented tricks — which I love! — but you better be as good as professional rassling.

So that’s the goal?

No, not at all. And I resent that. The goal is to delight. Whether you use darkness and horror, or whether you use smiles and celebration. Whether you use high art, like a whole lotta Shakespeare going on, or whether it’s the fine art I find on the bottom of a lot of skateboards. But to delight is your obligation as an artist, whether you’re leading an orchestra or playing a guitar.

Will you be doing some new songs on tour?

Yes. They’re all playable live. And since we’ve gained control of our videomaking facilities and all of the cameras and editing, we’ll certainly make more than one or two videos. We have several things coming up. We have a dress rehearsal with Kool And The Gang coming up at one of the local arenas here in about 10 days, and we’ll be filming that.

I was asked to watch your herding-dog handling video before we spoke. In it, you use high-pitched sounds to guide highly trained beasts who control large untamed herds. Isn’t that sort of what you do in your day job?

Nah. I think the contrast is the kind of cross-training that brings new to the proceedings. Most musicians, I think they lose their obsession, calling it a young man’s trait or game. It is when you are obsessed with what you are doing as an artist, or whatever you’re pursuing — perhaps you as a young journalist, as a young author, were obsessed and you pursued your heroes, whoever that may be. When I write, i think of everybody from Yip Harburg, who wrote Brother, Can You Spare A Dime? to Chet Flippo and Ben Fong-Torres, who wrote for Rolling Stone in the ’70s. I didn’t lose that obsessiveness. And when you’re obsessed like that, you think nothing of visiting other places and purloining some other ideas on your travels. You come back from Calcutta on your travels and go, ‘Listen to these chimes. we definitely gotta put this in the music.’ Or you’ve traveled somewhere and go, ‘I saw these guys doing shit on a sailboard — it had a sail on a surfboard, I don’t know what you call it, but man, I’m gonna Google it and I gotta try that at least twice.’ A lot of folks lose that. And the more that you get involved in other pursuits, it’s not a pursuit, it’s a community. Believe me, the neighbourhood involved in dog-handling is as rural as where I started: Newcastle, Indiana. Today I own three pickup trucks and there is no other car. There is no bumper sticker that says, ‘My other car is a … ’ There is no other car! Every one of those people that you interact with — and it’s not necessarily friendly. There’s adversity; it’s like horse racing, you hear, ‘Man that dog will not run.’ You hear those kinda catcalls every bit as frequently as, ‘Nice move, son.’ Those people are in your voice. Those people wind up in your music and your lyrics.

Speaking of adversity: You’ve had your share of it over the years with the Van Halens. And they always seem to present a unified front. Are things better on that front? Do you win any arguments?

I don’t know that there’s a whole lot of arguments to win at this point in time. It’s the same old routine for all these bands. Everybody values their privilege. And it is indeed a privilege and a gift to be able to have this job as opposed to a lot of the jobs the state offers. And I think everybody has sort of had at least one or two medical near-misses or at least one or two dental tragedies. Sometimes that’s all it takes. You get your teeth knocked out a couple of times and you start to realize you’re mortal. That illumination alone can rebind a band. And besides that, we’re gonna do it for world peace. I could answer all of of these questions with that. Do you want to do the ‘world peace’ interview?

No thanks. Now that you’ve got some momentum, is the plan to keep this thing going? Or have you given up even trying to look down the road?

For myself, I’m still chasing the ideal that initially compelled me, which is to write a superb song with a permanently memorable lyric. More frequently than not perhaps, we confine the theatre of our fame as artists to one or two or three people. That’s it. You find there’s somebody you think of every time you write something — what would he or she think of this? Would they think this was good? Do I think this is good or bad? One of the people who are my mentors is Yip Harburg. I was introduced to who that was when I was 12 or 13. He wrote the lyrics and the melody to Over The Rainbow and a whole variety of things. If you can do something that is as memorable and brings as much emotional content to the listener — I don’t know how old that song is — 50 or 100 years later, then you’ve made a contribution. For some reason, that’s just important to me. It’s like the first time I heard The Beatles sing Eight Days A Week in the back of a car. Today I can sing it to you having just heard it that one time. I don’t know if it’s a noble pursuit, but it certainly is a contribution of sorts. If i do it right, you’ll have a tune wedgie for the rest of your time.

Rock star, dog trainer, helicopter pilot, EMT — what else is on your to-do list?

You get around the bases and you will try a number of things quickly as a young person. But it takes a good eight or nine efforts at anything before you can really savvy whether it’s for you or not. I love the great outdoors — for me, my favourite poem is one sentence long: ‘Well, the sky should know me by now.’ It’s in contrast to the exchange of interiors that we experience as musicians. And it is like living in a submarine, from the inside of the studio, from the inside of an arena, from the inside of the bus. That is not at all a lament. I’m gonna say the one pursuit beyond my dogs is, I come from a background in the family of medical. Visiting my father as a resident at Mass General as a kid was a big occasion. Never occurred to me this was a hospital. It was just going to visit Dad. Everybody wore white uniforms back then. This was very early ’60s. My first job out of high school, I was a surgical porter working night shift down here in East L.A. actually. And I kept all of those certifications up. There was about 10 years when I had to grow my hair out and conquer the world. So I put that curriculum on hold. However, today I’m a New York State EMT. And I’m tactically certified. It is a constant spiral. It’s a loop. We call them evolutions, actually, of learning. And dealing with others. For example now, tactical training involves taking care of the search-and-rescue dogs as well as the search-and-rescue people. Planning for calamity — here in California, it’s flood, earthquake, etc. Do you know how to feed 100 people breakfast? I do. And as far as really learning tactical fieldcraft, you wanna know the best way to get a fire going if you’ve got somebody wet and freezing? Get to the commissary: Fritos are so full of fat. You light a Frito, you’re going to be amazed. I’m involved in learning. I seem to have a fascination for that. I always have. Now don’t go making me look smart; nobody’s going to want to talk to me. But conversely, if something bad happens to you, I can pretty much unfuck the situation until the right people show up.

I see we’re out of time. Is there anything else you want to add?

Yeah: Just because nobody understands you doesn’t mean you’re an artist. There is a point where you have to interact with the crowd. And I think Van Halen has always maintained that. We never got acceptable. We were never cool. Even when we happening. Even when we were the flavour of the week the first time, we weren’t cool, we weren’t cool. John Travolta and Saturday Night Fever were cool. And across the street, The Sex Pistols and The Clash were cool. Both of which, I bought their records many times since then. But we weren’t cool. We were just kind of an island on the way. And today we’re still not cool. Somewhere between Katy Perry and Muse. Somewhere between The Kings of Leon and Maroon 5. I don’t know that Van Halen ever really fit in. And it was not a conscious act. Many times we’re trying to imitate other people. It just comes out looking and sounding like us. Welcome to our little island. Abandon all hope … well, you know the rest.

But individuality is what ultimately makes you cool, isn’t it?

It’s always hard to do. You’re hitting on something that’s very interesting. I shared this with Wolf, being the young one in the band. For a great part of your life, particularly when you’re in school, it’s important that you be perceived as not uncool. That’s the most important thing: Don’t have people see you as uncool. In music, it’s the exact opposite. You have to define a unique place for yourself. You have to cut the anchor chain. And that’s a hell of a commitment. But I think we made that commitment a long time ago.

If you don’t cut the anchor, you don’t get anywhere.

The apple stays in the tree. You will range from the generic to the derivative. In fact, if that’s what you do, I’ll describe your music like a condom advertisement: Thousands of tiny little notes, urging you to let go with music so thin, you feel like you’re hearing nothing at all. You know who I’m pointing at. You can write their names later.