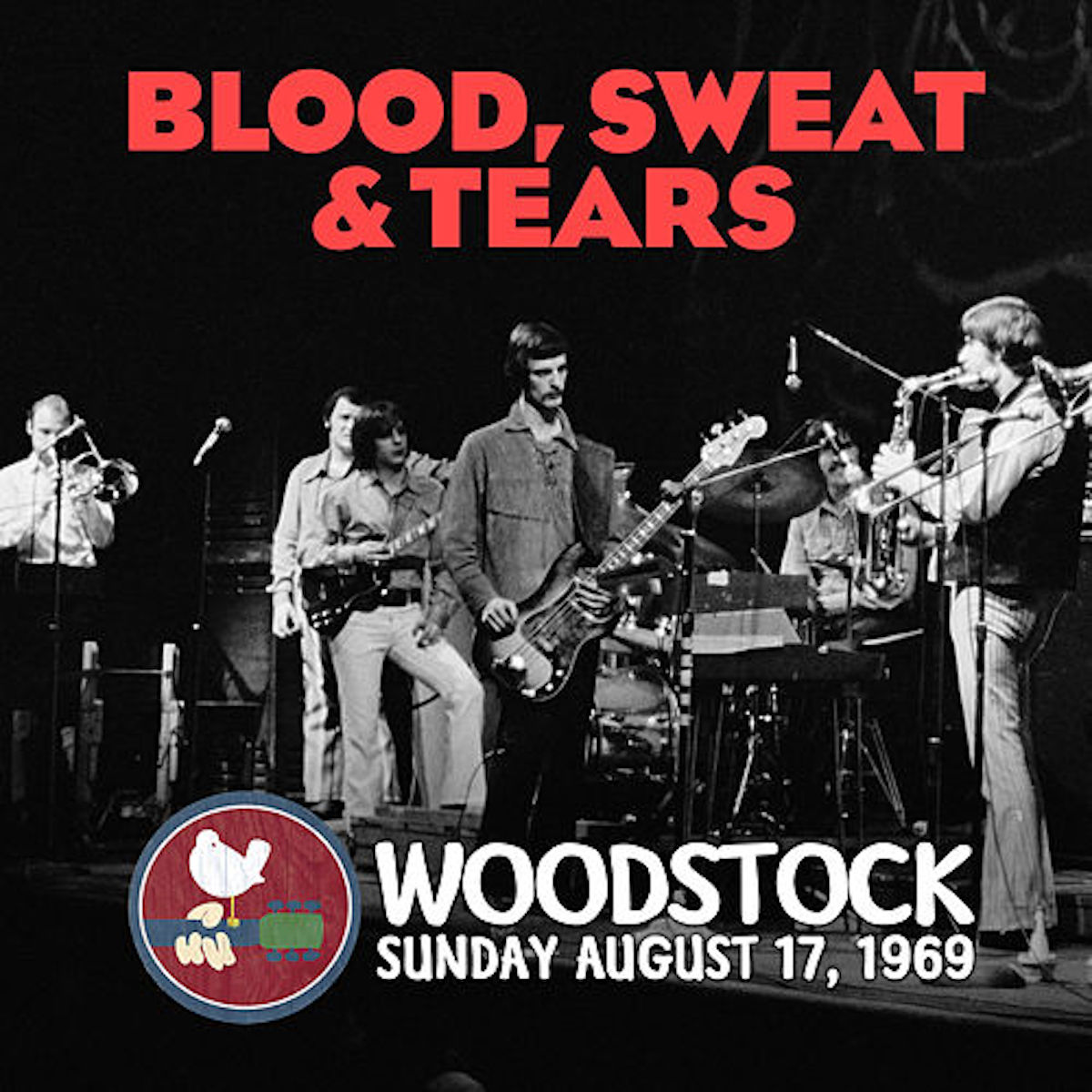

Timing is everything. Just ask David Clayton-Thomas. This weekend marks the 50th anniversary of his Woodstock performance with Blood, Sweat & Tears. So there’s no better time for the veteran Canadian singer-songwriter to release a new song and video — especially one whose call-to-action message is every bit as urgent and angry as he claims Woodstock was in its day. Never Again, a track from Clayton-Thomas’s upcoming album Say Somethin’, pointedly and plainly tackles the epidemic of gun violence in America, with lyrics that reference Parkland, Sandy Hook, March For Our Lives and more. Watch it below, and then check out my interview with the frank and outspoken singer — whose perspective on the iconic festival is vastly different from all the warm ’n’ fuzzy nostalgia currently being peddled:

For David Clayton-Thomas, Woodstock was more about hate and war than peace and love.

“We all have this Peter Max poster image of Woodstock — the Summer of Love and flowers and beads and all that,” says the former lead singer of Blood, Sweat and Tears. “In truth, that’s not what motivated Woodstock. Three-quarters of a million people didn’t march up there because of love. What motivated people was anger. People were pissed. Hundreds of kids were coming home from Vietnam in body bags every week. About 40,000 young Americans were dead. And when people had tried to protest at the Democratic Convention a year earlier, they had the riot police turned loose on them. But now, it’s all become peace and love and beads. That’s not how it was. That’s revisionist history.”

The veteran vocalist knows where he’s coming from — he and BS&T played a midnight set on the festival’s final day. Like many of the acts on the bill, they didn’t know what they were in for until it was too late. “It was a summer of concerts like that,” he recalls from his Toronto home. “There were a bunch of huge shows. And we had a hectic schedule — we had three records in the top 10 at the time. So all we knew up until the day before was that we were going to be playing somewhere up around Bethel — which was sort of a hometown gig for us, because we were a New York City band.”

They almost didn’t make the gig, he recalls. “I remember we sat at LaGuardia Airport for several hours. Everything had been brought to a standstill. We didn’t know quite what was going on up there — we thought it was a riot, because the National Guard had been called in. We thought we would have to blow it off, but eventually they loaded us on a bus and took us to a town about 20 miles south of there. We were in a little motel that was basically a staging ground for the artists. When we got there and they told us they were sending National Guard helicopters to fly us in, we began to realize how momentous an event it was.”

Not that Clayton-Thomas — clad in a black-leather outfit, complete with fringes — got to take in much of it. “We got on the chopper and they literally dropped us backstage about 45 minutes before we had to play. We did the show — it was an enormous amount of people, but over 100,000 it all looks the same — and they hustled us right off the stage and into the helicopters and took us out again. So 99% of my experience at Woodstock was onstage.”

But he was there long enough to catch a buzz off a spiked drink. “You could go backstage and take a deep breath and get high — there was a cloud (of marijuana smoke) hanging over the whole field. There was pot and hash and pills and LSD. There was a ton of drugs. I got into something accidentally, but I wasn’t radically tripping or spinning out of control or anything.”

Sadly, the bulk of BS&T’s set wasn’t captured by the film crew — their manager had the cameras turned off over because the band hadn’t been paid. “I still haven’t been paid,” he claims. “I don’t think anybody got paid for Woodstock. All the headliners were supposed to get $15,000 and a percentage of the recordings and the film. That was a big price in ’69. But there was no money to pay anybody by that point — the fences had come down, nobody was buying tickets, and the promoters were basically hiding in a trailer. I think they filmed two songs before they were shut down.”

He’s had to live down that decision ever since, he says. “I tried to explain to my young daughter once that Daddy was at Woodstock. She said, ‘No, I saw the movie.’ A lot of people got cut out of that piece of history — most of the big acts were not recorded. Of course, we didn’t know how important it would be at the time. You don’t recognize history when you’re making it.”

And as for that leather outfit? “Hey, it was cool in 1969! Believe me, I wore crazier things than that. I can tell you one thing: I don’t think I would fit it anymore.”